Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Newly arrived from Lagos, in the early nineties, Andrew Dosunmu, solitary and broke, sometimes slept in the Paris Metro. He had little in his possession beyond his clothes. And it was his manner of dress that first drew the curiosity, and then the care, of a stranger—the nascent fashion designer Lamine Badian Kouyaté. Lamine took Dosunmu into his home, and the two began collaborating on images: Lamine designing the clothes, and Dosunmu capturing them in motion and in life on Super-8 film.

“I didn’t know this brother from nowhere,” Dosunmu recalls to the cinematographer Arthur Jafa, in the introductory conversation to “Andrew Dosunmu: Monograph,” a collagist collection of Dosunmu’s portraiture used across film, music, video, and photography. But knowledge arises from the gravity of a slung belt, the height of a gele wound about the head. Dosunmu is a great chronicler of presentation as a portal to personality. This might explain his lack of faith in fashion per se; lauded as he is among editors and designers, having shot spreads for more than twenty years after those early days in Paris, he has eschewed becoming a fashion aristocrat. Even his commercial images are a rejoinder to the industry’s interest in using the body as a vehicle for platforming clothes. “It was never about what the people were wearing,” Dosunmu has said. In his vision of a contemporary world defined by wardrobe, Dosunmu works human-first—the wearer and her dress are in symbiosis with each other, and meaning flows between them.

Port Antonio, Jamaica, 2004.

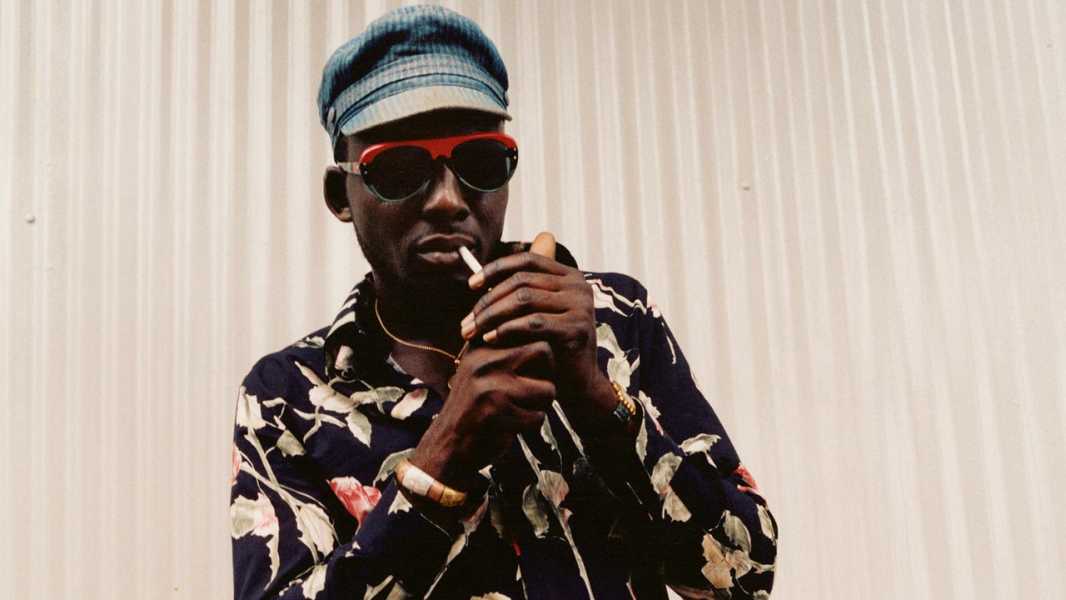

Dakar, 2011.

Dosunmu has made fashion images; he has directed music videos for musicians like Isaac Hayes and Tracy Chapman; he has created album covers for Erykah Badu and Public Enemy; and he has made films, including the 2013 feature “Mother of George,” a restrained anatomy of the marriage of a young Nigerian couple living in Brooklyn, stills from which are included in “Monograph.” But I sense refusenik humor in the packaging of Dosunmu’s beautiful book. The bluntness of “Monograph,” the title, could convey the stodginess of retrospective, but turning the pages one feels something closer to spontaneity, an edit led by the counternarrative instinct of a street photographer. The book deëmphasizes pedigreed associations—magazines like i-D, The Face, The Fader, and Vogue, or brands like Nike or Yves Saint Laurent, for which Dosunmu worked as a design assistant early in his career. The index identifies most of the images via geographical location. Dosunmu calls Brooklyn and Lagos his home bases, but his interaction with the world is itinerant. The book is a travelogue. Dosunmu brings Gabon, Cebu, Santiago, Dakar, Kingston, Accra, and Hanoi into a paradoxical proximity.

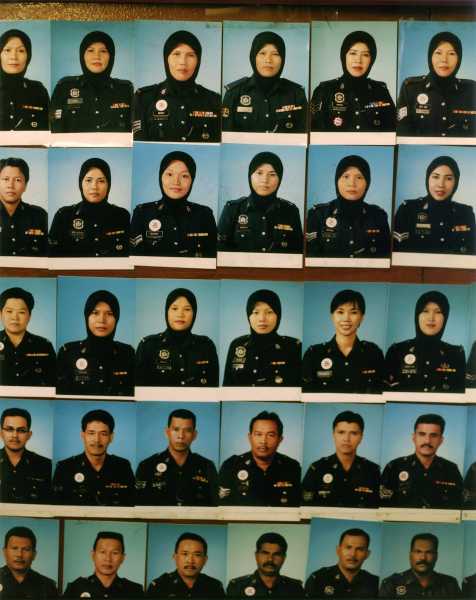

Kuala Lumpur, 2014.

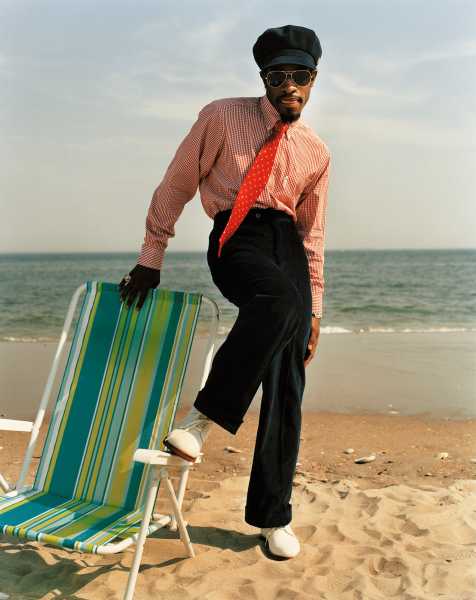

New York, 2010.

Dosunmu has added to his already created images, in the book’s organization, a layer of argument, derived from his use of quasi-diptychs. For example, Dosunmu has placed his mise en abyme capturing of a grid of I.D. photographs of Malaysian men and women, officers of some sort, next to his portrait of the musician André 3000, in a starched dandy look, at the beach, his tongue jutting out sexily. It is as if Dosunmu is recycling his own images to suggest resonances: the stone-faced enforcers meeting the Black American entertainer, both making use of the power of costume. In another diptych, Dosunmu pairs two women, one from the village of Pokot, Kenya, and the other from Salima, Ecuador. Both have bags slung over their shoulders, beaded bracelets encircling their wrists. Dosunmu’s timing creates the sense of international affinity: the Pokot woman, possibly shy, gives his camera her back, while the Salima woman, older, more confrontational, meets his camera’s gaze.

Salima, Ecuador, 2016.

Pokot, Kenya, 2012.

Dosunmu has created a catalogue of presentation that is, sometimes, stylized and posed, like the Malian studio portraitist Malick Sidibé, whom Dosunmu once shadowed. Dosunmu makes the street his studio. In his individual portraiture, Dosunmu delicately explores the revival of the idea of the Black diaspora, evident in the unexpected unification of stuff. In one portrait, taken in Lagos, a man stands in the doorway of a building, flip-flops on his feet, the top button of his jeans undone. A bucket hangs from the grate of a window. We cannot see the Yoruba shrine inside the building—the reason for the bucket, which is used to collect offerings from people who wish to go inside. The mystery of the spiritual clashes, amazingly, with the symbol painted on the building’s façade, flanking the half-undressed man: it is the Playboy logo, produced, it seems, from a stencil. How did that logo come to Lagos? Are we looking at a symbol of light sleaze? A comment on rampant Americanization? Or an image of winking coincidence? A correlating image, I found, is a portrait taken in Crown Heights. The sitter shapes his fingers into a diamond, a shape that parallels the kente-patterned trousers and head wrap that he wears. But wait—his Haile Selassie and Pan-African necklaces hang against a Gucci color-block hoodie. Because Dosunmu is not a polemic artist, our minds are free to roam about the migrations of these men, and that may lead us to stop worrying about origin stories altogether. We metamorphose into avatars of this bystander artist, asking nothing more of our subject than to step into our frame.

Lagos, 2004.

Aja, Nigeria, 2010.

In Dosunmu’s group portraiture, his camera widens, and his approach grows more explicitly documentary. We wonder how he insinuated himself into the scene. I am particularly taken with his images of worship, as they cause us to wonder about his own relationship to ritual. How did Dosunmu draw so close to the ceremonial participants on the beach in Aja, the Yoruba people who wear white robes and extend their arms toward the rush of the ocean? Back in the city, this time Mumbai, Dosunmu memorializes another image of collision. Traffic, human and vehicular, is broken up by images advertising the light-skinned heroes of Bollywood films. The man in the foreground, darker-skinned, is somehow both foregrounded and backgrounded, his blurred form complicating the harmony of the cultural hegemony above him. He stands still, hands on his waist, unaware of Dosunmu. But is he unaware of the advertisement?

“Am I a filmmaker? Am I a creative director? Visual artist? Am I a photographer? Why do I need boundaries?” Dosunmu asks rhetorically, in his talk with Jafa. “Monograph” embodies this spirit of shape-shifting inquiry in an era that commits virulently to certainty. ♦

Mumbai, 2005.

Ho Chi Minh City, 2018.

Ouidah, Benin, 2016.

Sourse: newyorker.com