Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

“The New Art: American Photography, 1839–1910,” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through July 20, is a wide-ranging and evocative exhibition that charts a period of explosive growth in photography, as one format improved and supplanted another, helping to establish photography as a popular art form. The technical and scientific advances on display, leading from the unique daguerreotype to the mass-produced calling card and stereogram, give meaning to what might otherwise seem a dry, academic exhibition. Photographers, many of them amateurs and “unknown artists,” were literally taking the medium into their own hands and exploring the potential of a new form of expression and perception.

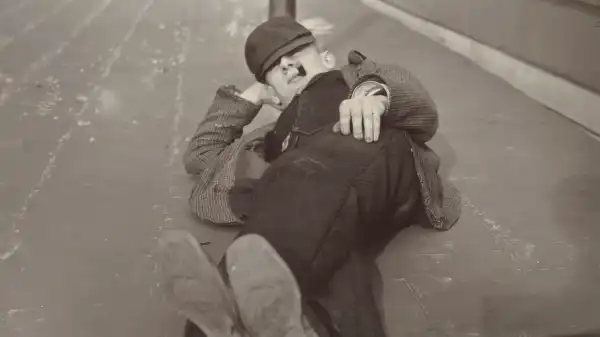

Roller Skate and Boot. Albumen silver print from a glass negative, 1860s.

Focusing on works produced in the United States, New Art also describes the country and its democracy as defining itself through its individual elements. Because the daguerreotype was the unique result of a labor-intensive and expensive process—a wall text describes “an image formed on a silvered surface of copper impregnated with iodine” and “developed by the hot vapor of mercury”—its use was generally limited to studio portraiture. Posing before painted backdrops, with draperies and props reminiscent of stuffy funeral homes, lawyers, businessmen, and society ladies dressed as if for a wedding reception remained perfectly still for as long as it took for the image to be captured, typically the twenty to forty seconds during which most of these examples were created. Each finished plate, reflecting like a mirror, was mounted on a brass mat, often hinged to a silk or velvet-lined panel that closed to form a book-like case, not unlike a cosmetic compact. The Met’s collection of works, assembled from the private collection of the American photography dealer William L. Schaeffer and a “promised gift” to the museum, references the format’s association with establishment wealth and power while displaying a variety of subjects: a farmer with tools, a blacksmith at his anvil, a dapper young man with a rooster, and two children in posthumous portraits on display for official viewing.

Sourse: newyorker.com