The war over American mythology continues apace.

One of the first pieces I authored as a new hire for The American Conservative was titled, “The Myths We Tell Matter.”

The brief post was inspired by a visit at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello. After moving to Washington, I’ve tried to make a point to visit historic sites up and down the mid-Atlantic. As a Southern California native, I simply did not grow up surrounded by battlefields and homes of the early Republic. Where I’m from, the closest things we have to Monticello and Mount Vernon are the Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan Libraries—which, as far as alternatives go, are quite acceptable ones.

“The myths we tell ourselves as a nation, and teach our children, matter,” I wrote. “Stories like that of Washington and the cherry tree, archetypal representations of the ideal American identity, reveal to posterity the wisdom and virtues of our nation—the very people who have toiled to keep this republic for us. Today, malevolent forces are attempting to erase these stories and dismantle our national inheritance to rewrite it for themselves.”

It ended with a call to action: “become proactive defenders of our national heritage, including its myths, for they have more wisdom than any university humanities department could ever hope to hold.”

I was writing more than a year after the death of George Floyd that set off a chain reaction of iconoclasm. In 2023, that tide of destruction ebbs and flows, but nevertheless continues to rise.

In October, the Washington Post gained special access to the foundry tasked with melting down the statue of Robert E. Lee that once stood in Charlottesville, Virginia. The statue, removed in 2021, was handed over to Charlottesville’s black history museum, who wanted to melt down the metal and repurpose it in another piece of ‘artwork.’ Some sought to defend the statue’s honor and filed a lawsuit that the monument ought to remain intact or at least be repurposed in a way that maintains the memory of that difficult period. They suggested turning Lee’s statue into Civil War era cannons was a good compromise.

But there’s no compromise with those who delight in destruction.

“Well, they can’t put Humpty Dumpty back together again,” Andrea Douglas, the executive director of the museum, said as Lee’s dismembered metal body melted in the furnace, the Post reported. “There will be no tape for that.”

University of Virginia religious studies professor Jalane Schmidt was also there for some unspecified reason. “No cannons,” she sniped, according to the Post.

The Post put out a haunting video of Lee’s incandescent, metal face melting atop the furnace. For the likes of Douglas and Schmidt, melting Lee down seemed a suitable substitute to crushing the real man’s skull.

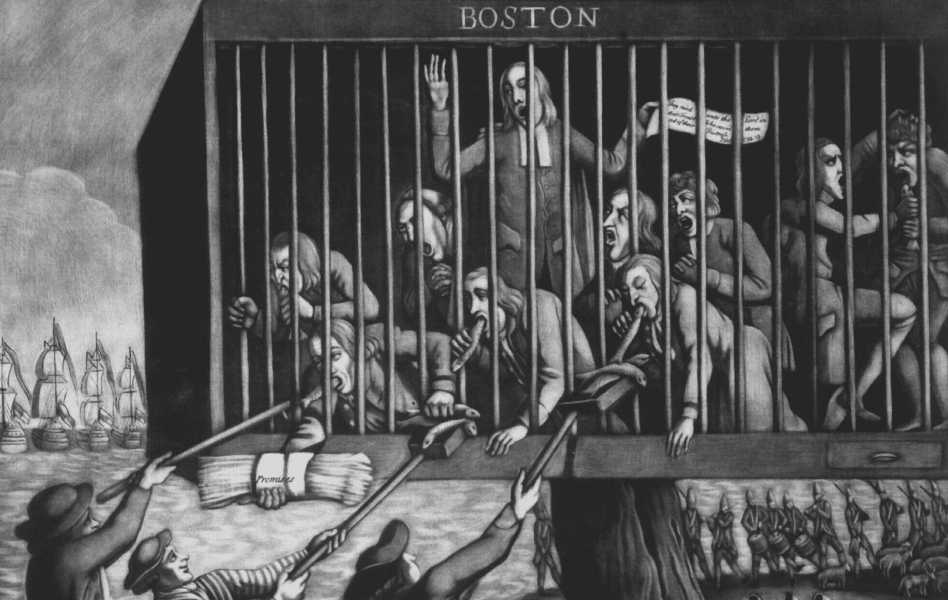

Two days prior to the 250th anniversary of the Boston Tea Party (keep an eye out for more TAC coverage of the anniversary), the Post was at it again.

Theodore Johnson, one of the Post’s contributing columnists whose “research and writing primarily explore the role that race plays in electoral politics and democratic culture, and its influence on the national narrative and the American identity,” has come out with a piece titled, “Was the Boston Tea Party an act of terrorism? It depends.”

Surprisingly, however, Johnson, also “a retired U.S. Navy Commander following a two-decade career that included service as a White House fellow and speechwriter to the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff,” spends very little time discussing what is and is not terrorism. In fact, the word terrorism is only used once: A reference to Benjamin L. Carp’s scholarly work that suggests some might consider an act similar to the Boston Tea Party as an act of terrorism today.

“There’s another version of the [Boston Tea Party], one less suitable for national mythology,” Johnson writes: “A horde of White men disguised themselves as Native Americans—coppering their faces and donning headdresses in the same tradition that would lead to blackfaced minstrel shows decades later—to commit seditious conspiracy and destroy private property.”

First, let’s quit pretending Floyd’s apostles give a damn about private property, but I digress. Johnson then reveals the true purpose of popularizing this version of the Boston Tea Party.

“A nation’s myths—exaggerated or imagined as they might be—shape its identity,” Johnson writes. The heroes in the myths of the Founding era and early Republic, however, “don’t look like the majority of Americans today.”

“Many of us descend from people labeled threats or, at best, sidekicks and free riders,” Johnson continues. “It leaves us wondering when we’ll get to be the protagonists in a core national myth.”

“It’s for this reason that there’s a growing clamor for new American stories,” Johnson claims. But who is clamoring for these new stories? It might be worth taking note of the pronoun Johnson decided to italicize. Johnson continues:

Not because the lessons of the foundational myths are invalid but because heroes should look like the nation they embody, the people they represent. Being able to see yourself in a story validates both the person and the example. Harriet Tubman and Rosa Parks and Thurgood Marshall, for example, made the United States truer to its principles. They demonstrated how a previously excluded people can be the fullest expression of—not a threat to—the nation’s virtue.

Subscribe Today Get daily emails in your inbox Email Address:

“New stories,” Johnson writes, “disrupt old myths.” He does admit that “the folks who identify with the people in the earlier telling feel displaced.” What is the source of this feeling? Johnson says the tension lies in “which of us is at the center of the story.”

There was a long period of time—one that ended not very long ago—when Americans of all different backgrounds and persuasions delighted in the expansion of their nation’s mythology. John Henry is an American folk hero; Harriet Tubman might still end up on some currency; no one speaks poorly about Rosa Parks, whose unwillingness to move on that Montgomery bus was anything but spontaneous. The American story was a shared one: Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass.

The tension is not two sides jostling for centrality. It is one side yearning for the revival of a shared American story while the other systematically tears out pages. If the battle over centrality isn’t the tension yet, this seems like a surefire way to get there.

Sourse: theamericanconservative.com