The photographer Nan Goldin, remembering her friend and portrait subject Greer Lankton, wrote that Lankton “created magical kingdoms.” Lankton, who died in 1996, at the age of thirty-eight, was a trans artist who was part of New York City’s East Village scene. She sewed, constructed, and painted exquisitely ragtag and ever-evolving, often human-size characters, which she brought to life in window displays at the boutique Einstein’s, in diorama-like sets and gallery installations, or in her own apartment. Capturing these worlds in enthralling, funny, and gutting photos, she developed a kind of candid, intimate portraiture practice of her own.

“Ballerina,” 1981.

“Sissys Bedroom,” 1985.

Dozens of these images are found in the exhibit “Greer Lankton. DOLL PARTY” at Company Gallery (on view through December 3rd), hung on the black walls of the gallery’s lower level. It’s the artist’s first solo exhibition in New York since her 2014 retrospective at Participant Inc. That landmark show assembled a group of her dolls, which had not been seen publicly for years; many of the artist’s sculptures disappeared, at least for a time, dispersed among friends and collectors in a community and art world devastated by AIDS. This show, like a delayed coda, shifts the focus to Lankton’s image-making, casting her poseable figures as fluid actors, appearing in spontaneous snapshots and shifting tableaux.

Images in the exhibit “Greer Lankton. DOLL PARTY,” on view at Company Gallery through December 3rd.

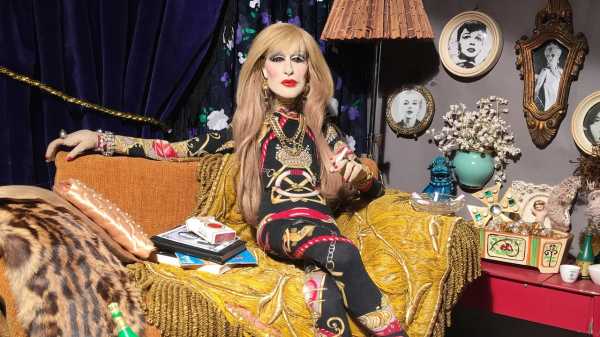

Some of the works here, such as ones based on Jackie O. or Diana Vreeland, comment on so-called high society, while others, such as tributes to the performers Ethyl Eichelberger and Divine, sketch Lankton’s countercultural cosmology. “Candy Darling at Home,” from 1987, is a vision of courtly opulence, showing Lankton’s extra-long-limbed representation of the Warhol superstar in a richly textured sitting room, bejewelled and dressed head to toe in a Hermès-inspired print. A simpler, full-length portrait of the same doll, from 1987, depicts her nude but for a boa in hot pink.

“Hermaphrodite,” 1981.

Earlier pictures show a different facet of Lankton’s figurative preoccupations, a strain of work inflected by surrealism and horror. “Hermaphrodite,” from 1981, with its nightmarish blue cast, is an explicit, spread-legged, natal image of a doll, shot as if standing at the foot of a birthing bed. Photos of dolls undergoing surgery, disassembled (as in “Ballerina” and “Red Womb,” from the same year), along with a selection of some of Lankton’s smaller creations—disembodied genitals, a belly button, the spiked papier-mâché torture device of “Jesus’s Cha-Cha Heels”—almost form their own show within a show. The cluster of fraught works seems to narrate, in fragments, a journey of embattled embodiment.

“Jesus’s Cha-Cha Heels,” 1986.

Most of the photos are presented as digital prints, but also on view is a selection of Lankton’s beautiful Polaroids. The loveliest have the look of miniature paintings. A tiny instant photo, from 1986, of Lankton’s severe Peggy Moffitt doll—heavy-lashed with a bowl cut, based on the famed nineteen-sixties model—is lit like a Rembrandt, with the doll’s face and gesturing hand emerging from the dark. The strikingly composed triptych “Jackie Kennedy,” from the previous year, has a doubled image at its center, an eerie mirror view, featuring the artist’s version of the former First Lady, dressed as she was the day her husband was killed. She wears the famous pink suit, the roses of her bouquet occupying the foreground like dark, bloody spots.

“Jackie Kennedy,” 1985.

Although Lankton frequently chose icons and celebrities as subjects, her brightest star was Sissy, an autobiographical doll whose physical transformations and daily life paralleled Lankton’s own. Lankton developed and deconstructed Sissy throughout her career. In “Sissys Bedroom,” from 1985, she appears both louche and vulnerable: splayed out on a comforter, her form as attenuated as an Egon Schiele, the doppelgänger wears nothing except scarlet stockings—not even a wig. “Sissy Modeling Paul Monroe’s Piano Hat,” from 1986, is a relatively rare closeup, in which a music-themed millinery design rests heavily on Sissy’s tilted head.

“Sissy Modeling Paul Monroe’s Piano Hat,” 1986.

Pictures of Sissy are of special importance because, even though many of the dolls pictured here have been located and exhibited in recent years, she—a magnum opus of sorts—has never been found. It’s fitting, then, that “Sissy and Cherry on the Stoop of Einsteins” is the first image you encounter in this treasure of a show. Wearing a maid’s uniform, in the company of a little white dog (real, not sewn), Sissy sits smoking, as if distractedly presiding over Lankton’s magical kingdom, in a vignette of jarring, indelible charm.

“Sissy and Cherry on the Stoop of Einsteins,” 1987.

Sourse: newyorker.com