Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

When I turned twelve, my dad decided that it was time for me to go to Hebrew school and get bat-mitzvahed. This was a surprising reversal, as my parents, much to the disappointment of our extended family, had never been particularly observant. (As a child, I sent my grandmother into a fit when I announced that my favorite food was ham.) The decision was especially striking because it came from my father, a man so laissez-faire about my education that it was a miracle I finished elementary school. At twelve, I could barely read in English, much less Hebrew. For this reason, any spark of interest from him about my direction in life was treated with awe and gravitas; it was like seeing the Pope drop off his dry cleaning. If my father said I should go to Hebrew school, that was where I would go.

The synagogue that my parents joined was not the most convenient (there was one on our block), not the one with the most family history (that one would have been either in St. Louis or in Omaha), not the most prestigious (that’s on the Upper East Side, across from the zoo). It was neither the prettiest nor the one their friends were part of. But it was directly on Gramercy Park.

Gramercy Park is a rectangular plot of land in Manhattan. It was established, in 1831, after Samuel Ruggles, a politician, developer, and urban planner, bought the deed to a swamp and gave it to the city; the park takes its name from the Dutch term “krom moerasje,” meaning “little crooked swamp.” Unlike Union Square, Gramercy’s more debased sister to the west, also developed with help from Ruggles, the park is famously private. Although the neighborhood known as Gramercy Park has expanded out as far as Stuy Town, access to the actual park is limited to those who live on the lots designated in Ruggles’s deed. It is the only remaining private park in Manhattan, and the only legitimate way to get into it is to be so silly, stupid rich that you could probably afford to buy your own park (though not in New York City).

Ruggles believed that creating a private park where the upkeep was funded by the surrounding properties would incentivize New York’s richest to move “uptown” and build their mansions there. The area would develop itself, the park increasing the value of the neighborhood in perpetuity. Therefore, it was in the financial interest of the city—a fledgling one that needed private dollars to grow—to grant the park tax-exempt status. A beautiful park exclusively for the wealthy was a good thing; it would benefit everyone.

Each of the forty buildings around the park pays an annual fee for access: two keys per lot, every pair costing fifteen thousand dollars. The lock changes every year. Initially, the keys were made of gold; in a lurch toward frugality, they’re now nickel alloy. Heavy is the pocket that carries the key. Many of them are owned by individual households, and around a third are carefully managed by the buildings, for residents to check out for a stroll. But there are also less legitimate ways of getting in, such as staying at the hotel on the park, which had a set of keys until it closed in 2020, or joining one of the surrounding clubs, such as the National Arts Club or the Players club. Lastly, there is the synagogue.

At Hebrew school, I was put in a class for slow learners. (Their names have been changed here.) There was Isaac, a boy who carried around a miniature shofar in his pocket and blew it at inopportune times, though arguably there are few opportune times to blow a ram’s horn in modern life. There was Anna, who had dyslexia, which might’ve put her ahead of me since Hebrew is read from right to left. Then there was me, nothing diagnosed but not for lack of trying. In this class we would play hours of Hebrew Jeopardy!, a loose approximation of the real thing, a flimsy con to get A.D.H.D. tweens to focus on what sound “ט” made. And my father would disappear until it was time for pickup.

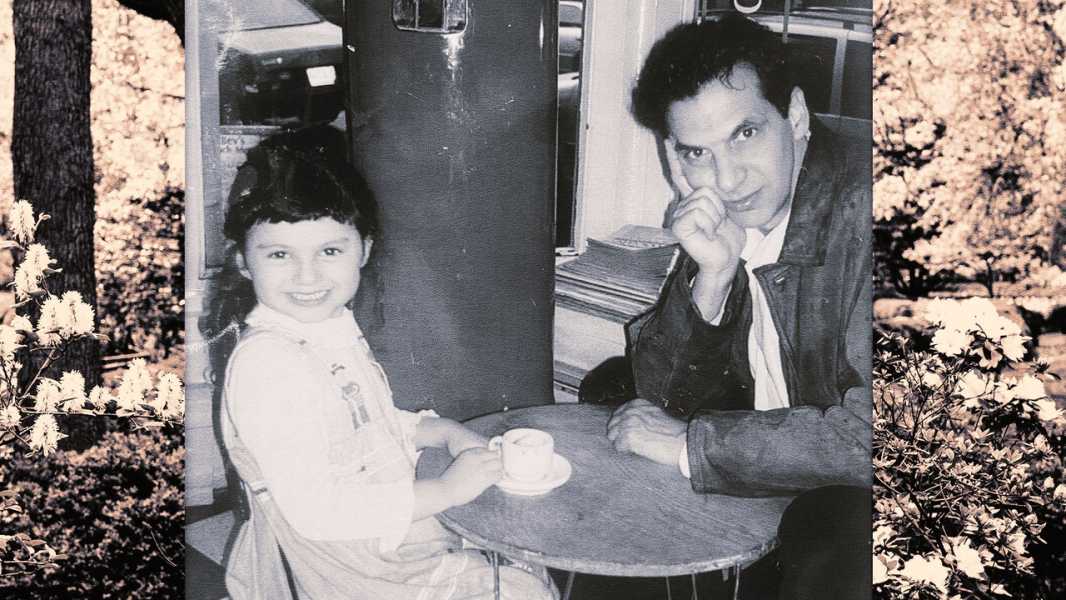

My father, Michael, is a fifth-generation Nebraskan. He grew up riding horses. The state has produced famous politicians, orators, and talk-show hosts, of which my father could have been any; instead he is a lawyer and author. He speaks cleanly, unencumbered by regional flair, but that void in his speech is actually the trademark of Omaha. He has inspired articles with titles like “Michael Rips Is the Most Fascinating Omaha Native You Have Never Heard Of” and “Who on Earth Is Michael Rips?” My father has an aversion to the socially standard way of doing things. He is known among friends for his brilliance, for having navigated the straits between artist and legal eagle without losing an oar. He clerked for the Supreme Court and lives in the Chelsea Hotel. On the warmest day of the year, he can be found in a coat and tie; he never sweats.

When I started Hebrew school, he insisted on picking me up, which was unusual for him; typically I’d walk home in a gaggle with other kids who lived near me. We would take the long way home, around the park, hitting every side and then doubling back. At the corner, he would level a poignant last look at the park, and we would depart. On these walks, my anxieties—Isaac did this, and Anna did that—were expunged of seriousness as my father offered solutions ranging from the disastrous (“Get your own shofar!”) to the merely bad.

One day, my father arrived late to pick me up, and his tie was stuck in his pocket. What was that sheen on his forehead? He struggled for air. Gone were the wayward pondering looks, replaced with jerky over-the-shoulder glances. On our walk past the park that day, he urged me to quickstep in my Mary Janes. Ultimately, I was too preoccupied by my own big life problems (upcoming bat mitzvah, breasts growing but not the areolae) to dwell on his strange behavior. I had been in Hebrew school for several months and was harboring resentment; school is a lonely place for an idiot to be. I envied the students in the regular class upstairs in the attic, the ones who started on time, who didn’t have to say “Kosher Rules for three hundred” every time they answered a question. The teacher of the slow learners’ class seemed to have given up on the idea that I might ever read Hebrew, and gave me an audio clip of my Torah portion to memorize. The cheater’s way into adulthood. I was depressed about it.

My father’s and my weekly strolls around the park continued. As we walked, he would compulsively announce its positive qualities. Other parks, he moaned, had turned into outdoor gymnasiums, with the athletically inclined jogging and Frisbeeing, people singing “Happy Birthday” in modulating pitch, picnic-goers chewing loudly, odors wafting from hot-dog carts, children playing, dogs fetching, sexually aroused adults canoodling, and all number of other horrors. Gramercy Park, created by Ruggles as a place of transcendental contemplation, had no “Happy Birthday” and no parfum de hot dog. The rules of the park were severe, and the head of the Gramercy Park Block Association was rumored to patrol with a clipboard: no smoking, drinking, or sport playing; no photography; no pets; no musical entertainment or Frisbeeing. Ruggles’s park was a place for Waldenian reflection. Our walks were historical tours; my father knew everything about the park but its inside.

Often, my father would go on about the wildlife in the park: the chestnut and elm trees around the perimeter, hyacinths, daffodils, rhododendrons. Here was a man who regarded organic things with distaste and had moved from Nebraska to New York to avoid them. But to him Gramercy Park was The Park, the Platonic park. Sometimes I would stop and sniff, convinced that the scent of magnolias was wafting illicitly through the fence.

Could they really be happy, I wondered, gawking at the people inside the park as they gawked at me. As our walks progressed, I became increasingly put off by the park visitors’ Schadenfreude. It was a failure as a “private” park; it wasn’t private at all. If I couldn’t have something, I didn’t want to see it, and I certainly didn’t want others to get off on my exclusion. Was this to be the rest of life—locked out of things I didn’t want to be part of?

Eventually, my dad seemed to notice my adolescent misanthropy. “Come with me,” he said one day at pickup. He led me back into the synagogue. I felt sure that he was about to bestow upon me some rare slice of paternal wisdom. Now, on the third floor, we stood between two doors. One opened to the upper level of the main sanctuary, a balcony with rows pointing toward the altar, the other to the clerical offices. “Stand here in stillness and pay attention to what may appear,” he said. Then he jimmied the handle and entered the offices.

It seemed that he was saying, not in words but in gesture, “Nicolaia, at points in your life, there will be a crossroads. How you choose to navigate them is your prerogative. Will you perform these rites empty of connection? Will you be a Jew who understands Judaism only through an iPod Nano? What is your relationship to God? Do you have one?” These were the thoughts running through my head.

For the first time ever, I was moved to walk into the sanctuary of my own volition. I sat and considered. Any major revelations I might’ve had were interrupted by commotion coming from the rooms next door. There inside the rabbi’s office was my father. And there inside the rabbi’s office was, unfortunately for my father, the rabbi.

My father had meant his words literally. He was attempting to station me as a watchman, and I had abandoned my post. In fact, my enrollment in Hebrew school was the first step in a long and perpetually unravelling plan to get a key to the park. As my father later explained, “If the Zoroastrians had set up on Gramercy Park, you would’ve been a Zoroastrian and would’ve had to learn Avestan.” When he disappeared at drop-off, he imagined himself inside. In our leisurely walks around the park, he was examining the gate.

His first attempt had taken place several weeks prior; he had checked out the key and taken it to a local locksmith. At the locksmith he began to feel the minutes ticking by, and considered that the locksmith was either hand-forging the key or contacting the authorities. As the sound of a police siren grew close, my father’s long defunct sense of preservation flared up and he assumed a hearty jog, loosening his tie in the process.

This time, he had decided on a different tack: slipping by the rabbi’s office when he thought the rabbi wasn’t there. It was an innocent enough effort. He assumed that, while he was there for the park, the rest of the congregants—wonderful, respectful, and kind people—were there for God.

We were ceremoniously escorted outside by an elderly man, one of those ancient enforcers who could often be found loitering in the lobby. This man, who could barely walk, received a final burst of strength, his disdain firing through his veins as he waved us onto the street. He locked the gate of the synagogue behind him. We were on our own, cast out of both the sensuous and the sacred.

As we idled in limbo between the two, my father questioned me seriously. Where were you? Where did you go? How did we end up here? Don’t you know how to follow instructions? I walked over to the park and stuck my face between the bars. This, from a man with no perceivable guidelines for his own life, was too much. “No!” I cried. He patted my shoulder. “Just as I taught you.” Look at it this way, he continued, we were now part of a very important group. In this excommunication from Judaism, he explained reasonably, we’d joined a third, more rarefied community than the privileged in the park. Though our infraction was relatively minor, my father suddenly viewed himself as part of a long line of prominent Jews shunned by other Jews: Baruch Spinoza, Mordecai Kaplan (the founder of the Reconstructionist movement), Maimonides. Nothing stuck to him: life was funny, poignant, bizarre. He found what he didn’t realize he was looking for—the covenant of the unconventional. I finally got to be something I wanted to be: his accomplice.

I had my bat mitzvah, thanks to the iPod Nano, though my family’s relationship with the synagogue ended soon after. Against intention, this period was the most pious moment in either of our lives, my father’s and mine, as closeness to God was revealed as not a place but a search. While my Torah portion fled my mind instantly, what stayed with me years later was the sense of enlightenment my father and I shared as we stood outside the park that final afternoon: paradise was, in the end, nothing but a little crooked swamp. How lucky I felt to be on the same side of the fence as him. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com