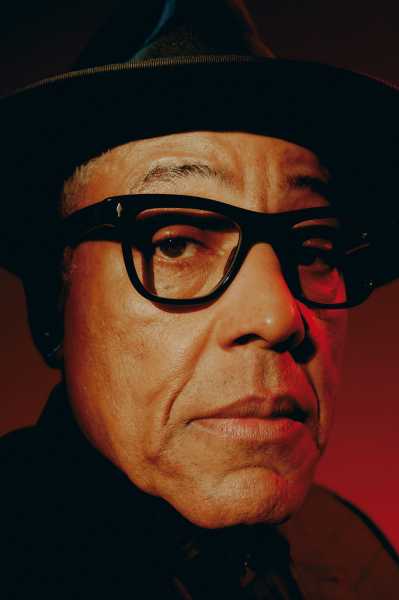

When Giancarlo Esposito stepped off the escalator at MOMA, a trio of security guards—all young men, Black or Latino—greeted him with knowing salutes. Who, I wondered, did they see? Was it Gus Fring, the fussy, stoical drug lord of “Breaking Bad” and “Better Call Saul”? Or Stan Edgar, the biotech C.E.O. who manufactures superheroes in Amazon’s Marvel satire “The Boys”? Maybe they’d seen him in “Do the Right Thing,” shouting a question as contentious in contemporary-art museums as it was in Spike Lee’s Bed-Stuy pizzeria: “How come you ain’t got no brothers up on the wall?” But Esposito, a tenacious veteran of stage and screen who has become one of the most familiar faces in television, has played so many dastardly bosses and charismatic troublemakers that it almost didn’t matter which one. In every role, he mesmerizes audiences with a coiled intensity that he credits to military school, the slings and arrows of a volatile profession, and a lifelong commitment to mindfulness. “My karmic journey is to be told what to do and accept that and do it the best I can,” he said. “I realize one of my strengths is to control the chaos.”

Esposito, a graceful sixty-four-year-old with sharp dimples and slicked back salt-and-pepper curls, seems to be everywhere these days. His imperious likeness graces memes, video games, and ads for Dirty Devil Vodka; at fan conventions, masochistic fans beseech him to stare them down. “They want it, just like children want discipline,” the actor told Conan O’Brien during a recent interview. “They want me to cut their throat, they want me to give them the look . . . they want me to call them employee of the month.” Despite jocular complaints that he’d like to try a good guy, the baddie beat is treating him well. Recently, he’s starred as a master thief in Netflix’s experimental miniseries “Kaleidoscope,” and a Caribbean dictator in the popular first-person shooter Far Cry 6.

When I saw Esposito at MOMA, he was enjoying a break from a shoot for Francis Ford Coppola’s sci-fi epic “Megalopolis,” in Atlanta. By some accounts, the project has been tumultuous, but Esposito, who’s playing the mayor of a revolution-wracked city, had only positive reports: reuniting with Laurence Fishburne, his onetime roommate; “falling in love” with scene partner Dustin Hoffman; and learning from the irreverence of young talents like Aubrey Plaza. Between engagements, he was visiting his daughter, Kale, at their shared downtown apartment, and catching up on art and theatre across the city. “Did I just miss the Calder mobiles?” he wondered; weaving through the midday crowds, he pivoted smoothly between selfie requests, my questions, and his own bursts of curiosity. From the balcony, we gazed at the shape-shifting forms of Refik Anadol’s “Unsupervised,” an A.I.-generated video installation that looked like an unruly galaxy in need of a firm hand.

This month, Esposito returns to Disney+ on the popular “Star Wars” series “The Mandalorian,” playing Moff Gideon, a cape-swirling insurrectionist in a remnant of the Galactic Empire. He spent most of the last two seasons scheming to abduct the fan favorite Baby Yoda—presumably, to throw him in a blender and pulp him for midi-chlorians—only to land, relieved of his Darksaber, in the custody of the New Republic. “All I wanted was to study his blood,” Gideon tells Mando (Pedro Pascal), the masked hero, in a climactic rescue sequence; menacing the gurgling green infant with an energy blade, Esposito achieves a degree of campy malevolence not seen since silent-movie villains tied damsels to train tracks. But the actor doesn’t believe in “villains,” and he hinted that a comeback in the new season, possibly involving an effort to democratize the Force, might show his character in a new light. “What are we all looking for but that energy?” Esposito said. “Maybe he wants that child so that he can take what he has and give it to all of us.”

It’s become a cliché to observe that Esposito is actually a very nice guy. The actor who strikes fear into the hearts of strangers—once, a “Breaking Bad” fan tried to yield him her place in the bathroom line—would seem to have little in common with the exuberant, demonstrative man who approaches his profession with such joy and humility. What he does share with his characters is an old-fashioned sense of masculine responsibility. Perhaps his most celebrated monologue, from “Breaking Bad,” is addressed to Gus’s then protégé Walter White (Bryan Cranston), an ex-chemistry teacher who’s wavering on his decision to enter the drug trade. Walter tells Gus that he’s made too many bad decisions hoping to support his family. “Then they weren’t bad decisions,” Gus replies. “What does a man do, Walter? A man provides for his family . . . he does it even when he’s not appreciated, or respected, or even loved. He simply bears up and he does it. Because he’s a man.”

Gus, an ascetic criminal mastermind, may not even have a family. But Esposito, a divorced father of four daughters, gave dimension to the role by drawing on his own struggles with childhood trauma and the isolation of life on the road. I was surprised when, just a few minutes into our conversation, he started tearing up, remembering a hug with his youngest daughter during a difficult stretch in the two-thousands. “I hadn’t seen her in four months, and she said, ‘Papa, are you O.K.?’ ” he recalled. “And I said, ‘I just need to be touched.’ ” Esposito channelled that feeling in the last season of “Better Call Saul,” for which he won a Critics Choice Award. In Gus’s final episode, while relaxing at a wine bar, he yearns to reciprocate the attentions of a flirtatious sommelier (Reed Diamond). At the last minute, he balks, losing and painfully reconstructing his composure in a closeup that showcases Esposito’s talent for the inner drama of discipline. “I find it’s healing for me,” he said. “Growing up too fast as a child on Broadway, as a performer who always had to be on, who always had to deliver—many of the things I missed, I haven’t given back to myself yet.”

Esposito began his life as a roving child of the stage. His mother, Elizabeth (Leesa) Foster, was an opera singer from Alabama who was touring Europe when she fell in love with a Neapolitan stagehand. They soon married, and Giancarlo was born in 1958, in Copenhagen, where Elizabeth was performing in a split bill with Josephine Baker. The family eventually settled down in Elmsford, New York, and Giancarlo had his Broadway début when he was only ten years old, playing an orphaned fugitive from slavery in the Civil War-era musical “Maggie Flynn.” “I learned how to tap dance from Michael Bennett and Anita Morris and Tommy Tune in ‘Seesaw’ without ever taking a lesson,” Esposito told me. He appeared in four Broadway musicals before he’d turned fifteen.

Another demanding apprenticeship was growing up Black and Italian in a largely segregated New York City suburb, especially once his parents’ marriage dissolved. Elizabeth responded by enrolling Giancarlo in Catholic parochial schools and then in a military academy; surprisingly, he loved both, confessing that the routines of cadet life had nourished his “fastidious” personality. “They were checking the corners on your bed, and if your bed wasn’t made, you got slapped around, you got beaten,” he whispered, almost nostalgically, in the quiet gallery. “You had to pay attention . . . and for me, what I do is pay so much attention—to my breathing, to my tone of voice.” Every morning, he woke up at five to serve as an altar boy, and he considered a priestly vocation before realizing that he “wanted to wear those vestments inside.”

What it all added up to was a talent that thrives on tension, a voltage derived from the gap between Esposito’s aggressive charisma and equally pronounced flair for constraint. (Even on “Sesame Street,” where, in his early twenties, he guest-starred as a camp counsellor, Esposito laid down the law for a homesick Big Bird.) “I started to realize that you have to fall in line, but I’ve never wanted to fall in line,” Esposito told me. Rebellion involved dropping out of high school to develop a night-club act in California, and, when that failed, bussing tables at a dinner theatre back home. He dreamed of acting in dramas in film and television, determined not to become a “song-and-dance man,” but also hedged his bets, enrolling at a two-year college and working as a cameraman at local basketball games.

A formative rejection kept him on the right side of the lens. During an audition for “Taps” (1982), the casting director Shirley Rich told Esposito that he had no idea how to act for a camera. He left in tears, but after learning to draw back his Broadway presence in small plays, as Rich had suggested, he got the part. “I did it all with my eyes,” he said. In “Taps,” Esposito plays a student officer at a fictional military academy, whose cadets stage an uprising to prevent its sale to real-estate interests. He prowls the dorms stealing care packages, battling townies with a young Tom Cruise, and scoffing at Captain Kirk’s cautiousness in “Star Trek”: “Why doesn’t the man use his phaser?” (He eventually found the right franchise.) His big-screen début coincided with a star turn in Charles Fuller’s Pulitzer-winning play “Zooman and the Sign” as Zooman, a teen criminal who accidentally kills a little girl in a shoot-out with a rival gang. Esposito’s seething side-stage monologues, which rage against his circumstances in an attempt to excuse the murder, earned him an Obie Award, along with the admiration of an N.Y.U. film school grad named Spike Lee.

It was Lee who first gave full expression to Esposito’s aptitude for lawful evil. In the musical comedy “School Daze” (1988), set on the campus of a fictional H.B.C.U., he cast the actor as Julian (Big Brother Almighty) Eaves, a preening fraternity tyrant who delights in paddling pledges—one called Yoda begs for mercy—and loathes the anti-apartheid activism of his popular rival, Dap (Laurence Fishburne). “You do not know a God-damned thing ‘bout AF-RI-CA!” he rebukes Dap in a memorable sidewalk confrontation, enunciating each syllable like a drill sergeant. “I am from Detroit. Motown. So you can Watusi your monkey ass back to AF-RI-CA if you want to!”

He dialled it up in “Do the Right Thing,” as Buggin Out, a fast-talking hothead who precipitates the climactic attack on Sal’s Pizzeria. The character’s monologues are almost glossolalic in their grievances—“Who told you to step on my sneakers? . . . Who told you to be in my neighborhood? Who told you to buy a brownstone on my block, in my neighborhood, on my side of the street?” he challenges a white Brooklynite—and Esposito’s antic performance stood out, even in a film teeming with talent. The experience was also cathartic for Esposito as a Black Italian American, forcing him to confront the tensions between his communities. After a climactic screaming-match scene with Danny Aiello, full of improvised slurs, the two actors burst into tears. “We hugged each other for at least twenty minutes,” Esposito said. “We didn’t want to take that anger out of the scene, didn’t want to take it away with us.”

Over the next twenty years, Esposito’s career glided but never quite soared. He played bit parts in Lee’s later films, appearing briefly as an assassin in “Malcolm X.” There was a standout performance in Jim Jarmusch’s “Night on Earth,” and a promising stint as a detective on NBC’s “Homicide,” followed by years of small roles in soap operas and gangster dramas, which soured him on playing street toughs. “I made my living on that little tinge of anger inside me, that allowed me to be an angry young Black man and rob some white lady onscreen,” he told me. “I felt like doing that might be who I become forever, and I knew I had more to give.”

It seemed appropriate that we’d spent most of the afternoon in an exhibition devoted to the German-Swiss artist Meret Oppenheim, whose own varied career is often reduced to a single fur-covered teacup. Esposito walked right past it, beelining to a series of celestial multimedia paintings whose textures he found enchanting. One canvas reminded him of the Hindu goddess Kali: “She’s gonna destroy me as I knew me, and there’ll be a new me that’ll emerge,” he exulted. For many years, painting was his main creative outlet, and in the early two-thousands “painting the world” as a director promised an escape from the doldrums. He débuted with “Gospel Hill” (2008), starring Angela Bassett and Danny Glover, but its earnest narrative about a neighborhood’s struggle against developers failed to find a wide audience.

Then, in the aftermath of the financial crisis, Esposito went bankrupt. “I suffered in that middle ground that got squeezed in the industry,” he said. “It was crushing.” At one point, he considered suicide to secure a life-insurance payout for his family. He borrowed money from his eighth-grade teacher, who predicted that, with four children to support, he would likely never recover from the collapse. A friend pulled him out of depression with “Who Moved My Cheese?”, a best-selling self-help book that features two entrepreneurial mice learning to embrace change. “I could never talk about my bankruptcy, for years, until I realized it was perfectly healthy to talk about,” he told me. “But it deepened my work as an actor. We don’t always win. Sometimes we fucking lose.”

The show that freed Esposito from purgatory was “Breaking Bad” (2008-13). The series, created by Vince Gilligan and set amid the anomie and adobe subdivisions of Albuquerque, New Mexico, follows Walter White from the quiet desperation of a cancer diagnosis through his Nietzschean rebirth as a crystal-meth kingpin. Yet before he can accomplish this transformation, White must outmaneuver Gustavo (Gus) Fring, a local immigrant businessman. By day, Gus owns and operates a fast-food chain, Los Pollos Hermanos, where, all smiles and pious platitudes, he works shifts alongside his staff and caters charity events for the Albuquerque police department. By night, he’s a ruthless drug lord, bringing the same commitment to customer service into the underworld; in one terrifying scene, he eviscerates one of his own minions with a box cutter to make a point to his meth cooks. Scarier than the act itself is the time Gus takes to change clothes before and after the killing. Esposito says only five words in as many minutes: “Well? Get back to work.”

Gus was written as a marginal character, but Esposito doesn’t believe in small parts. “It was Vince that inspired me by writing in the stage directions, ‘hiding in plain sight,’ ” he told me. “That gnawed at my guts.” His punctilious menace so mesmerized viewers that Gus became one of the principals, attaining such popularity that AMC advertised the spinoff series “Better Call Saul” (2015-22) with a travelling pop-up version of Los Pollos Hermanos. Gus’s appeal has many dimensions, including the Zen-like quality of his compartmentalization and the dark comedy of his immigrant success story. In both of his guises, he’s the perfect American: a scrappy entrepreneur who loves the free market and embodies corporate sociopathy. “This is America,” he reassures employees in an episode of “Better Call Saul,” just after a drug-related altercation in his restaurant. Offering to pay for trauma counselling, he explains the attack as a futile attempt by old Mexican acquaintances to extort an innocent businessman in a land where “the righteous have no reason to fear.”

Perhaps the key to Gus’s magnetism is his respectability’s ironic edge. Many critics analyzed whiteness in “Breaking Bad”; some argued that it was a fable about the erosion of white-male moral authority, whereas others decried a story in which a lone white chemist dethrones brown cartels with his “pure product.” But Gus, a smiling chicken vender who works tirelessly to put the cops at ease, is a no less racialized figure—a nightmare, to some, and a fantasy, for others, about the compulsory performance of innocence evolving into a kind of superpower. Gus is the answer to the question: What if the pressure for Black men to act nonthreatening created the perfect cover for a kingpin?

At the museum café, I made the mistake of offering Esposito a comfortable seat with a view of the city, while I sat in a hard chair facing the entrance. “I almost wanted you to switch,” the actor told me; from a young age, he’s struggled with hypervigilance, a tendency that became acute during the pandemic. In early 2020, Esposito had just moved into a new house in Albuquerque, where shooting was set to begin for the final season of “Better Call Saul.” “All my daughters thought that I would surely die,” he told me. “They seriously thought, ‘He’s going to fade away to nothing, because he never stops.’ ” Esposito, a man of strict routines, wasn’t emotionally prepared for the disruption. The lack of work also raised the spectre of a second bankruptcy. “How long before I drown?” he asked his accountant, who told him that he had about a year. “I scrapped everything for a few weeks and said, figure out how to be with yourself outside of the world, outside of people handing me my validation.”

Esposito let his beard grow and planted a vegetable garden. He got to know his eccentric neighbor, a heavy drinker who sleeps in a tent, and deepened his interest in the Greco-Armenian spiritualist G. I. Gurdjieff. Most of all, he decided that it was time to focus on projects with more personal meaning, especially when it came to his long-cherished desire to play an “everyman.” One result is “Parish,” an AMC show that débuts in September; Esposito stars as a New Orleans chauffeur in the employ of a Zimbabwean gangster. Another chance has been the latest season of “Godfather of Harlem,” a nineteen-sixties crime drama starring Forest Whitaker, with Esposito in the uncharacteristically righteous and unbuttoned role of Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., the congressman, preacher, and Civil Rights hero. Watching him grandstand, sermonize, womanize, and blackmail Dixiecrats in Congress, I found myself wishing that more directors would let him flex his talents as a showman.

Strolling through the museum, Esposito recalled a memorable childhood encounter with Josephine Baker. He was in Toronto, travelling with his mother, when she realized that her old acquaintance was performing at their hotel. Elizabeth told her son to go out and buy a single red rose; that night, they sat close to the stage during the performance. “Two songs in and Josephine Baker breaks into ‘La Vie En Rose,’ ” Esposito told me. “She sings the first verse. My mother says, Now.” After he offered her the rose, Baker took Esposito’s hand and pulled him onstage, singing the next verse directly to him. “Now, this is Josephine Baker, in a black sequined dress with the body of a goddess,” he told me. “She had to be in her seventies. She was not young. And she finished that verse, and she held my hand, and she takes the rose, and she says”—at this, he dropped his voice to a growl and gave me the Gus Fring look—“ ‘Now go on back to your mama.’ ” ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com