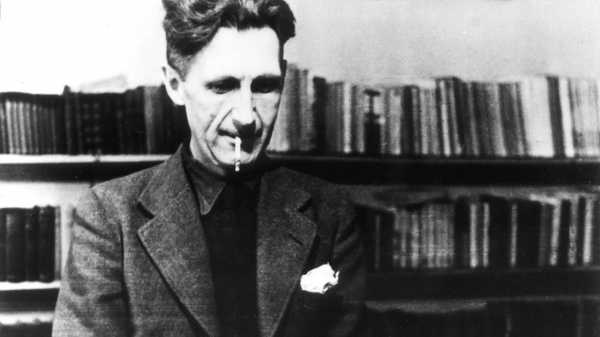

Every so often, George Orwell’s essay “Shooting an Elephant” finds me

and demands a reckoning. The essay, first published in 1936, describes

an incident that may or may not have actually taken

place,

from a period of Orwell’s life, in the nineteen-twenties, when he was

living in Burma and serving as an officer of the Imperial Police Force.

For five years, he dressed in khaki jodhpurs and shining black boots,

patrolling the Burmese countryside—in his own words, “the white man

with his gun, standing in front of the unarmed native crowd.” A normally

tame elephant, in a fit of musth, tears through a village, and Orwell is

called to deal with the situation. After the animal tramples an Indian

man to death, Orwell feels compelled to kill it in front of a gathering

audience.

In certain respects, Orwell recognizes the theatricality of his

position, the repugnance of British imperialism, the fulsome

geopolitical spectacle in which he is “an absurd puppet pushed to and

fro by the will of those yellow faces behind him.” To shoot the elephant

seems to him an act of murder. But to be a white man of authority, a

sahib, is “to appear resolute, to know his own mind and do definite

things.” When Orwell finally kills the elephant, it is not out of

conviction but fear of not acting his part.

I first read the essay years ago, as a student of English literature,

and then, again, as an aspiring writer in English. More recently, I read

it as a reporter on assignment, after riding in a Beijing taxicab while

an exuberantly patriotic radio host held forth on China’s astronomic

ascent since its days as “the Sick Man of Asia.” Twenty-four hours

prior, Donald Trump had arrived in China for his inaugural diplomatic

trip.

It was the phrase “the Sick Man of Asia” that sent me back to Orwell.

The epithet is recognizable to every Chinese child age ten and above,

from history lessons in school. The term is emblematic of the great

shame China experienced after the nineteenth century’s Opium Wars,

when the Middle Kingdom was brought to its knees by the British Empire.

I moved to the States at the age of eight, and I had only a vague notion

of the term prior to my departure, but I learned my lesson during my

first visit back, three years later. In front of a former teacher, a

childhood classmate, aged eleven, asked, with a look that seemed to

teeter between mirth and mockery, “Are you an American now?” When I

stumbled, speechless, she added, as if she’d had the line cued up for

me, “Too good, are you, for the Sick Man of Asia?”

In “Shooting an Elephant,” Orwell explains that his job as a policeman

has allowed him to see “the dirty work of Empire at close quarters,” as

he puts it: “The wretched prisoners huddling in the stinking cages of

the lock-ups, the grey, cowed faces of the long-term convicts, the

scarred buttocks of the men who had been flogged with bamboos.” I

flinched when I first read these words, a dozen or so years ago. This

must have been how China, too, then seemed to the Western world, I

thought: besieged, assaulted, molested, bruised. Even in the early

aughts, it did not seem as if the country’s century of humiliation had

come to a close; China’s rise only made evident how much further it

still had to go. Reading Orwell’s words was, for me, to discover that

those scars of shame had not faded.

I read the essay for a second time when I was in my early twenties. I

had come to some understanding of how complicated history could be, of

the way that the nationalism that the Chinese government tried to

instill in its citizens also shaped the country’s profound sense of a

fall from grace. This time, I underlined the following lines with a

thick black marker: “All I knew was that I was stuck between my hatred

of the empire I served and my rage against the evil-spirited little

beasts who tried to make my job impossible.” Orwell quickly adds that

“feelings like these are the normal by-products of imperialism,” but I

immediately felt a heated confusion. On an intellectual level, I knew

what he meant, and I could imagine his dilemma exactly. But I couldn’t

help the queasiness in my stomach. What was the piece of myself that

recoiled at the thought that a white man could see yellow people like me

as little beasts?

In the Beijing taxi, as the man on the radio chattered, I caught a

glimpse of my reflection in the windowpane, one yellow face in a sea of

many. This is a curious moment to be an American journalist of Chinese

ancestry, when conversation, both global and national, often hinges on

the issue of identity. If I had ever believed that my heritage was

irrelevant to my work, then the weekly e-mails, Facebook messages, and

tweets that I receive commanding me to “go back where I came from” or

questioning my credentials as “an American” disabuse me of the notion.

As do the messages, issued with equal vehemence, apprising me of “the

shame I have caused to the Chinese people.”

Bias is inevitably named as my primary offense: it constitutes the only

point of agreement between those who think I am a shill for the Chinese

government and those who believe I have long been brainwashed by the

West. The charge seems to me both anodyne and anticlimactic. Yes, I see

the world through the lens of a Chinese woman who also happens to be an

émigré. Orwell could only approach life as an Englishman who was born in

India.

A little while back, I had a dream in which I found myself conscripted

as an international spy. None of the cinematic 007 sexiness seemed to

have seeped into my subconscious; instead, I was filled with an

indescribable dread, heightened by the fact that, mid-mission, I

realized that I had forgotten whose side I was working for: China or the

U.S. The only thing clearer than my fear was the imperative not to share

my inconvenient lapse of memory with anyone. I woke up with the sound of

my heart in my ears, sheathed in a thin film of clammy sweat.

My subconscious is not always so heavy-handed. It frightened me to think

that I could don the jodhpurs and boots with my words—but what if, to

counter the possibility, I slid to the other extreme? I described the

dream on Twitter, and someone responded by calling it “the plight of

journalists and translators everywhere.” But my fear was not succumbing

to bias so much as to the invisible force that compelled Orwell to shoot

the elephant. What voice of overarching authority could I, despite my

better instincts, be parroting? And what blinkered narrative, steeped in

craven half-truths—the kind that makes the dissolute soldier in each of

us mutter “little beasts”—might I have absorbed?

“I looked at the sea of yellow faces above the garish clothes—faces all

happy and excited over this bit of fun, all certain that the elephant

was going to be shot,” Orwell writes. “They were watching me as they

would watch a conjurer about to perform a trick.” Every piece of foreign

correspondence involves a bit of conjuring; when performed well, the

trick transports the reader to a place she may have never visited,

acquaints her with people she has never met, and puts her inside a story

she perhaps never knew existed.

But there are cards that a writer shouldn’t hide. A journalist begins in

ignorance, then hews a narrative out of newly acquired knowledge—guided,

in part, inevitably, by who she is, and where she came from. A writer

must confess her own little beasts, or else success, as with a magic

trick, will come at the cost of deception. Orwell knew better than

anyone the price of spectacle. “I should have to shoot the elephant

after all,” he writes. “The people expected it of me and I had got to do

it. I could feel their two thousand wills pressing me forward.

Irresistibly.” For every writer, there comes a moment when the will of

the world presses you forward, so close that you can feel their breath

and words and sweat, tempting you to shoot.

Sourse: newyorker.com