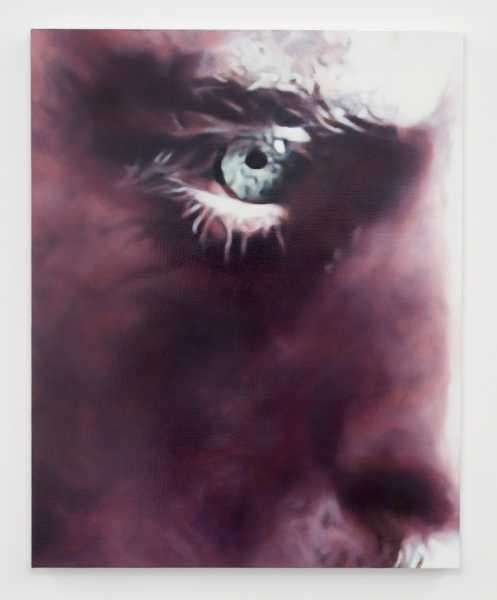

Judith Eisler, “Painter 2,” 2018; oil on canvas, 39.37 x 31.49 inches / 100 x 80cm

Artwork by Judith Eisler / Casey Kaplan

The first week of September brings an anxious back-to-school energy to the galleries of New York City, heightened, in recent years, by the concurrence of Fashion Week. On Thursday night, art lovers and clothes horses flowed together on the streets of West Chelsea like brackish water. (Which pack is fresh and which one is salty remains up for debate.)

If we’re being honest, openings are for schmoozing, not for looking at art, but a critic can form first impressions. For one thing, female painters are out in full force. East of the madding crowd (near the plant district), Judith Eisler, a native New Yorker, is having her first show in a decade at the Casey Kaplan gallery. Eisler, who now lives in Vienna, has been working since the nineties with one strict rule: she paints stills from movies captured on her computer (back in the day, she used a VCR), putting an art-house twist on the cerebral photo-realism of Gerhard Richter. In the past, her paintings have felt somewhat constrained, a little too cool. But her new subject, Derek Jarman’s “Caravaggio,” has inspired the most beautiful work of her career—painting about painting that is as lush as a hothouse bloom.

The gallery Cheim & Read, which is closing its public space to pursue private dealing, devotes its last show to the great post-Ab-Ex painter Joan Mitchell, who died in 1992. It’s a swan song that also flips the art world the bird: recently, Mitchell’s estate decamped to the almighty Zwirner. Neighbors in the same building, D. C. Moore and P.P.O.W., are showing the veterans Barbara Takenaga and Julie Heffernan, respectively. Takenaga is an abstractionist with a mystic’s interest in how the ecstatic can emerge from the laborious. Heffernan, who worships at the figurative altar of the Old Masters, continues to strike me as a little mawkish, but her chops are undeniable. Sometimes painting turns up where you least expect it, in this case gracing millions of beads in the wall hangings of Liza Lou, at the new flagship of Lehmann Maupin.

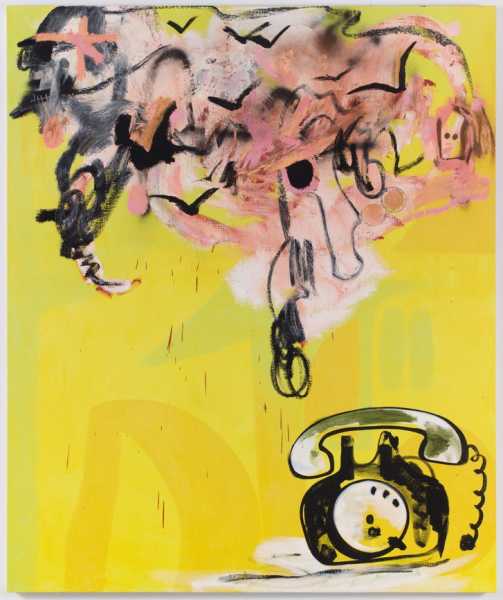

Charline von Heyl, “Dial P for Painting,” 2017; acrylic and oil on linen, 60 x 50 inches / 152.4 x 127 cm

Artwork by Charline von Heyl / Petzel

Perhaps the most exciting American painter right now is the German Charline von Heyl. The evidence: seventeen bristling canvasses currently hanging at the Petzel gallery. They are both a tour de force and a teaser: the artist’s midcareer survey “Snake Eyes” opens at the Hirshhorn Museum, in Washington, D.C., on November 8th. Von Heyl builds a future for painting by digging into its past; allusions ricochet from the angst of the German expressionist Otto Dix to the ornament of her contemporary Philip Taaffe. The vibrating indigo concentric circles of “Mana Hatta” (whose title riffs on the original name for her adopted home town of New York City) are pure Sonia Delaunay; the red polka-dot hares leaping below the circles remind the eye that each painter is her own Alice, falling through history’s rabbit hole. Von Heyl is a crackerjack colorist, but line is the star of her show. The acid-yellow and black “Dial P for Painting,” with its snappy depiction of a rotary phone, has a graphic intelligence worthy of Saul Bass’s best work for Hitchcock.

Sourse: newyorker.com