Earlier this summer, on the lot of Citi Field, in Queens, New York, a familiar scene was unfolding. Shifty-eyed men were plying their trade (“doses and rolls, doses and rolls”), halter-topped women were selling edibles out of wicker baskets, Hare Krishnas were proffering vegetarian burritos, and grizzled men were tailgating with their wives and young children. It was an hour before a concert by Dead & Company, and this was “Shakedown Street,” the unauthorized open-air market that has become as much a part of the Grateful Dead experience as the trading of bootleg concert tapes. The Grateful Dead was always known for its eclectic fan base, and its crowd has, if anything, diversified since 2015, when most of the band’s remaining members formed a spin-off group with the musician John Mayer. In the last three years, a new breed of Dead follower has emerged, who, perhaps inspired by Mayer’s own style, is most easily identified by his combining of tie-dye with stylish streetwear. For this fan, Dead & Company, and the scene that has sprouted around it, has come to represent rebellion and its material accoutrements.

In the shade of a parked truck, next to a tent in which a woman was loudly complaining of having spilled a beer on her dog, a small throng of young people, more than a few of whom seemed to be wearing Vans, vintage Dead T-shirts, and Ray-Bans, were congregating around two men hawking their merchandise out of a large duffel bag. Elijah Funk, in sandals and maroon socks, and Alix Ross, in dark sunglasses, with his long, dreadlocked hair tucked into a black cap, are the twenty-eight-year-old founders of Online Ceramics, a line of elaborately screen-printed and tie-dyed graphic T-shirts, beloved by the improbable subculture comprised of Deadhead streetwear fanatics. With their grab bag of hippie, D.I.Y. punk, and hip-hop influences, Funk and Ross’s designs represent an apex of the fashion world’s search for authenticity. Tees by Online Ceramics have been picked up by the cutting-edge Los Angeles menswear shop Union, and will be carried next spring by the taste-making élite department-store chain Dover Street Market. For these purveyors and their customers, however, the fact that Funk and Ross still sell their tees in parking lots is undoubtedly part of the brand’s cachet.

On the lot, a twentysomething man in Nike sneakers—designed by Virgil Abloh, the artistic director of Louis Vuitton menswear, for his own label, Off-White—selected an Online Ceramics tee made especially for the Citi Field concert dates, and asked to take a picture with the designers. The man said that his shoes cost “four hundred bucks, but they were down from maybe nine hundred.” The Online Ceramics T-shirt, however, cost only thirty. It featured a picture of a skeleton atop a New York City taxicab driving through a brick wall, below the words “It’s one more Saturday night live,” and was typical of Online Ceramics designs, which, like those of other small brands, such as Advisory Board Crystals and Cactus Plant Flea Market, can be loosely defined as hippie streetwear. With their extremely limited production runs and handmade aesthetics, these labels are often thought of by their admirers as producing fine art rather than consumer goods. Mayer, who has followed Funk and Ross’s career since 2016 and sometimes wears an Online Ceramics shirt to perform, described the tees’ graphics, which incorporate the Grateful Dead’s traditionally trippy symbology—skulls, dancing bears, roses—like nothing he’d seen before. “There’s as much Migos in there as there is Jerry Garcia,” he said, referring to the Atlanta rap trio and the Dead’s late lead guitarist. “There’s Post Malone and Houston trap. They’re building Online Ceramics iconography rather than Dead iconography.” He told me that he had recently seen Abloh in one of the shirts. “I was telling people a year ago, ‘This is like Nirvana,’ ” he said, adding that he expected Urban Outfitters to produce imitations soon. “Give it two months.”

Photograph Courtesy Online Ceramics

The T-shirt, one of the more consistent style staples of the modern era, is experiencing a particular moment of popularity. In the past couple of years, influential streetwear brands like Supreme and Palace have been reaching beyond their original target audience of urban skaters to teens, thirtysomething creatives, and moms in their forties. New versions of logoed tees are continually presented and snapped up at so-called drops—weekly unveilings of new, limited-edition merchandise. Meanwhile, high-end labels such as Vetements, Gosha Rubchinskiy, and Off-White have been introducing their own takes on graphic shirts. (In 2016, Vetements sold a plain yellow tee bearing the DHL logo in red—identical, to the untrained eye, to one sold by the courier-service company, but retailing for upward of three hundred dollars.) Perhaps most influentially, artists like Justin Bieber and Kanye West have stamped T-shirts (and hoodies and baseball caps and pants) with distinctive renderings of their names and song and album titles, setting off a craze for “merch” that has also spread to film-production companies, bookstores, and smoked-fish emporia.

It is within this context that Online Ceramics has taken off. Samuel Hine, the assistant style editor at GQ, attended a Dead & Company concert this summer, in Boulder, Colorado, and bought a yellow-and-purple tie-dyed West Coast–tour tee from Online Ceramics. “They sold, like, a hundred shirts in forty-five minutes,” he recalled of Funk and Ross. “It was, like, Shakedown Street Supreme.” The shirts frequently sell out—which only makes them more attractive to style mavens seeking to distinguish themselves from their peers. As Mayer put it, “I think of Online Ceramics like a band, and the T-shirts are the albums, and I want to collect all of them.”

For Ross, a Dead fan since high school, designing T-shirts was, at first, a way to pay for tickets to the concerts. As a student at the Columbus College of Art & Design, he became an avid taker of LSD, which helped him reach a different spiritual plane while listening to the Grateful Dead’s noodly jams. “I’ve seen him crying and slapping the ground at shows,” Funk told me recently. Ross and Funk, both from Ohio, attended Columbus College together, and felt that the Dead represented something that they wanted to re-create in their art. “The Dead had experimental music, they didn’t have a record label, they had super-D.I.Y., proto-punk ethics,” Funk said. “All we wanted to do was listen to the Dead and talk about the Dead,” Ross added.

After graduating, Funk and Ross moved to L.A. “We were super broke,” Ross told me. “We had, like, no money, essentially.” Funk—skinny and brimming with energy, with a blond buzz cut, wire-rim glasses, and a dense pattern of dozens of tattoos creeping up his neck and down his fingers—did some freelance design jobs and worked at a coffee shop. Ross, who is tall and lanky, with the low-key, dreamy demeanor of an early-seventies Topanga Canyon heartthrob, worked at a latex fetish shop in Silver Lake for minimum wage, assisted the painter Laura Owens, and helped out at a ceramics studio. “I had been making these flutes you could actually play—weird stuff,” he recalled. At one point, the pair thought they could produce these clay objects together. “I got, like, the domain for it—‘online ceramics,’ ” Ross said. “I just thought it was hilarious. What a goofy name to call a ceramics store!” But, in early 2016, their friend Sonya Sombreuil, of the cult line Come Tees, asked them to make a T-shirt for her booth at the L.A. Art Book Fair. “We were, like, this is our in, this is our function,” Funk recalled.

Photograph Courtesy Online Ceramics

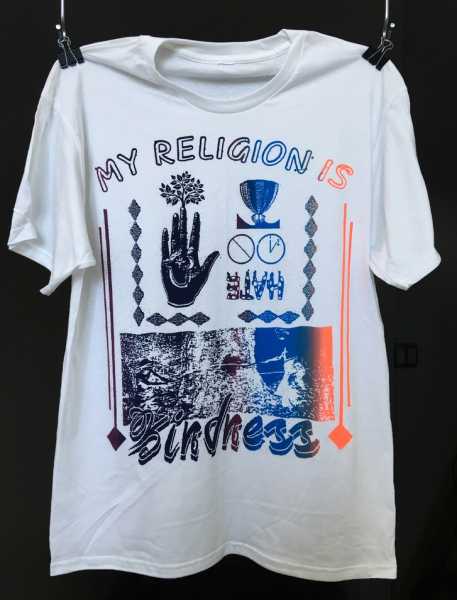

You can see the shirt that Funk and Ross made on the Online Ceramics Instagram account, which they officially launched in March, 2016. Like all of the brand’s designs, the T-shirt’s aesthetic is not immediately placeable, or even especially lovely in any conventional sense. Tie-dyed in spatters of olive green and purple, and printed with the phrase “My Religion Is Kindness” in a wonky font reminiscent of elementary-school worksheet graphics, the T-shirt also bears a hodgepodge of enigmatic symbols: a hand with a tree growing out of its middle finger; a diagram of two circles; the word “hate” in polka-dot letters, upside down; a chalice. It appears, at first glance, like a memento from a family reunion that one might come across at a provincial Salvation Army store. To look at the shirt is to feel one’s eye straining to take in something new, or at least newly reconfigured. Is this ugly? Dorky? Cool? Is it some sort of ironic stunt, a Mike Kelley–style art-school in-joke, or a sincere gesture?

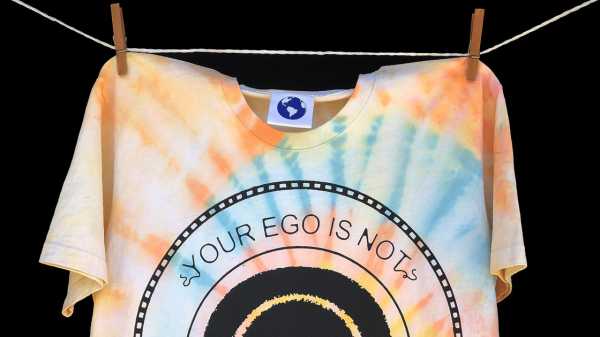

“We’re trying to see how far you can stretch something to the point where it’s just, like, a mystery, and then it’s, like, rad,” Funk told me, when I visited them in their studio, in downtown Los Angeles, this summer. He and Ross were sitting on upside-down paint buckets in one of the low-ceilinged, semi-dilapidated shacks in which the pair, with the help of two employees and some freelancers, now tie-dye and screen-print, by hand, hundreds of T-shirts a month. The 2018 Dead & Company summer tour was still under way, and shirts were selling out. Mayer had happened to wear the one style that hadn’t been selling well onstage the night before. “It’ll probably be jumping up now,” Funk said. Freshly tie-dyed shirts, in hues of green and purple and orange and yellow and blue, were coiled in rows, snail-like, on a table; shirts stacked in a pile to the side were printed, on their front sides, with the phrase “Your Ego Is Not Your Amigo” under a drawing of a jester in a striped cap, its long, pointy crown stretched in the shape of a circle, and, on their back, with the words “Let goooo now” on a red, smiley-faced butterfly. I later bought a shirt—a black long-sleeve printed with the words “World Peace” in multicolored handwritten letters—online. The first time I wore it, a barista at my co-working space asked me about it. “It’s so”—she seemed to be grasping for the word—“happy?”

In the summer of 2016, Funk and Ross bought tickets for the West Coast leg of the Dead & Company tour, and started to make Grateful Dead–themed merch to sell on Shakedown Street. Soon, the Instagram account @fromthelot, which documents Dead memorabilia and paraphernalia, began featuring Funk and Ross’s designs. “Every time the account would post, we’d get, like, a hundred and fifty new followers,” Ross said. (They now have more than thirty thousand.) Some of these followers would purchase Online Ceramics shirts online, on the brand’s lo-fi Web site, which links to Ross’s favorite L.A. yoga studio and the sign-up page to an organic-produce C.S.A.

There was something reassuring about the bustle of the L.A. studio, its limited, modest mode of production. (The designers buy unprinted, plain-color T-shirts from Los Angeles–based purveyors, for five to ten dollars each.) In one of the shacks, an assistant was busily screen-printing, while, in the room where we sat, a new employee, A. J. Kahn, a bespectacled twenty-two-year-old U.C.L.A. art-school graduate, his arms peppered with stick-and-poke tattoos, was organizing dozens of freshly tie-dyed shirts in large mounds, according to size. “Our T-shirts are very touched,” Ross said. “They’re being handled many times.”

As Kahn sorted the T-shirts, conversation turned to the D. A. Pennebaker documentary “Monterey Pop,” from 1968, which took as its subject the 1967 Californian music festival of the same name, and allowed a glimpse into the emergence of countercultural hippiedom. Kahn had been reading about the alternative school that Joan Baez established in Carmel Valley, in Monterey County, California. “It was, like, two-month sessions, and fifteen kids would just read and talk about concepts of nonviolence and how to avoid participating in the war,” he said. Ross looked awed. Kahn continued, “Residents who lived there for years came down on Baez and took her to court, talking about how, like, she was trying to set up a circumstance where Monterey would become the next Haight-Ashbury. There was this intense divide.”

Ross shook his head. “It’s too bad. Monterey sucks.” He paused for a moment, considering. “I mean, I like Monterey. Monterey’s awesome.”

Sourse: newyorker.com