Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this storyYou’re reading Critic’s Notebook, our weekend piece surveying the most captivating happenings in the cultural climate.

In a diary passage from August, 2015, Eleanor Coppola, the author, filmmaker, and visual artist, contemplates what motivates her—then a septuagenarian—to continue her artistic pursuits. “What objective drives me?” she muses. “Certainly not a fresh career at this phase of my existence. Not financial gain, although I admit I’d relish possessing a sum I’d earned independently. Not fame, but indeed, increased recognition would be pleasing within a family known for its prominence, where I’m perceived as the affable spouse, parent, grandparent at the periphery, or simply excised.” In reality, throughout her life, Coppola, who passed away in 2024, at eighty-seven, was mainly recognized through her husband, the Academy Award-winning director Francis Ford Coppola, and subsequently, her daughter, the director Sofia Coppola. The challenge of visibility plagued many American women of Coppola’s cohort, who matured shortly before the blossoming of second-wave feminism, and thus were compelled, as she puts it, to “prioritize assigned roles over who [they] genuinely are and what [they] aspire to do.” In Coppola’s instance, though, it was further intensified by the virtually blinding radiance of her celebrated relatives. Who was she apart from them? Did she even matter as an individual?

These inquiries are delved into, poignantly and forthrightly, in the newly launched posthumous compilation “Two of Me: Notes on Living and Leaving,” which assembles a range of Coppola’s diary excerpts from the concluding decade of her life. This isn’t Coppola’s inaugural publication; preceding it were “Notes: On the Making of ‘Apocalypse Now,’ ” which appeared in 1979, and “Notes on a Life,” from 2008. Both earlier works provided accounts of personal tribulations the Coppolas faced, such as the demise of their eldest son, Gian-Carlo, in a boating mishap, as well as behind-the-scenes glimpses into significant cultural events the family participated in—most notably, Francis Ford Coppola’s almost doomed struggle to finalize his Vietnam War epic. (Eleanor Coppola also co-directed, with George Hickenlooper and Fax Bahr, the remarkable 1991 documentary “Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse,” which featured footage she captured in the Philippines during the turbulent filming of “Apocalypse Now.”)

“A publishing house that considered my initial book remarked, ‘Now that you’ve drafted the notes, go back and compose the full book,’ ” Coppola discloses, wryly, in “Two of Me.” However, part of what differentiates Coppola’s methodology is its declared dedication to insignificance. While her placement in the relative margins has evidently been a source of discontent—at one juncture, she voices the “rage” that surges within her when she contemplates “how much women of my generation were molded to heed directives from authoritative male authorities who determined what was optimal for the ‘little lady’ ”—it has also afforded her the chance to intimately investigate a more private, concealed realm that might not have been as readily accessible to her as a subject had she been at liberty to assume a more prominent, public role during her years.

This rather limited domain has frequently acted as an enhancement to her husband’s more expansive panoramas. “I am the spectator, the onlooker observing the action as if within a theatre,” she pens, in “Two of Me,” regarding visiting Francis on location while he helms his latest and likely final cinematic spectacle, “Megalopolis” (2024). Likewise, in “Notes: On the Making of ‘Apocalypse Now’ ” she chronicles a demanding location shoot on a shore, entailing the imitation of a napalm attack. “The napalm detonated perfectly with the jets, soaring through the frame, flawlessly. . . . Twelve hundred gallons of gasoline ignited in roughly ninety seconds,” she writes. Positioned about half a mile from the blast site, she notes, simply, that she “perceived a potent surge of warmth”—the succinct, reticent prose implying her stance as merely a figure in the landscape, sensing rather than dissecting, experiencing rather than reacting. In an earlier diary entry from the same day, she mentions, again with minimal detail, the distinction between the very few women and the numerous men she observes on location. “The out-of-shape American men are becoming tanned and robust,” she writes. “The women appear weary.”

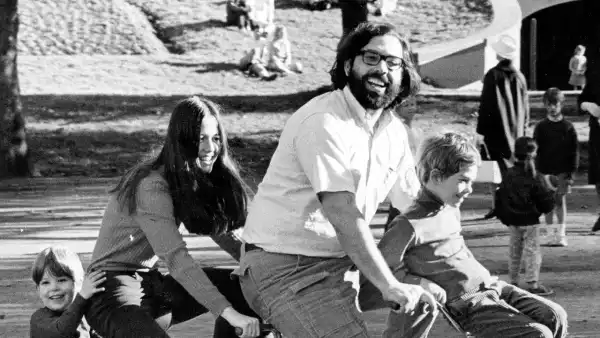

Photograph by Jimmy Keane

Photograph by Jimmy Keane

Among these fatigued women is Coppola herself, and “Two of Me” implies that this exhaustion didn’t merely arise from the gruelling “Apocalypse” shoot she depicted in her initial “Notes.” It also stemmed from the intrinsic strains within the Coppola marriage itself. Eleanor Coppola was a woman who, as she states, yearned to lead her life as an “adventure” while engaging in her own “artistic endeavours” and nurturing children on film sets, “like a circus troupe,” but had to concurrently satisfy the needs of her brilliant, temperamental, occasionally errant husband, who expected her to be a “quintessential wife, joyfully committed to caring for our children, establishing a pleasant home, and supporting his profession.” For the majority of her existence, she was indeed—to expound on the book’s title—“Two of Her.” Who among us wouldn’t be depleted by such an intrinsically paradoxical situation?

“Two of Me,” nonetheless, does portray the commencement of an unanticipated opening, through which Coppola was eventually able to gain a degree of liberation from this duality—one that wasn’t within her reach during much of her adulthood. In 2010, an X-ray examination unveiled a rare form of tumor developing in Coppola’s chest. Although the physicians she consulted with advised her to commence chemotherapy to diminish the growth, she feared that the procedure would lessen her standard of living and opted to postpone it, instead—utilizing alternative therapies and undergoing scans every half-year to monitor the tumor’s gradual progression. (She endured for an additional fourteen years, undergoing the growing tumor’s significant adverse effects solely in the concluding couple of years of her existence.) Within the book, she recounts her family’s dismay at her resolution to reject conventional therapy: “Francis informed me that he and the children must be paramount in any determination I made, and they were eager for me to proceed with a therapy, an action, a solution that would remove me from harm’s way,” she chronicles. Coppola, however, refused to yield to their prodding, even though, as she concedes, she possessed “no ‘rational’ justification or proof” to validate her choice, and, as I continued reading, I pictured with what annoyance and perhaps resentment I might have responded had someone close to me declined established medicine to address a critical ailment.

Yet from an alternate, possibly more symbolic perspective, Coppola’s choice was sensible, at least according to the terms in which she viewed her existence. “I was taken aback to comprehend that I was so conditioned by my upbringing to be a compliant girl and adhere to doctor’s orders that it had never registered to me that the choices for my life were mine to make,” she articulates. The tumor was “[a]n excellent instructor,” a “sudden awakening” that ultimately urged Coppola to peer “out from behind the guise of [her] kin.” Though the growth was a restrictive entity, an impediment “pressing against [Coppola’s] heart and lungs”—and, as such, not dissimilar to the stresses she was accustomed to navigating during much of her life as a wife and mother—these restrictions were what ultimately permitted her to comprehend the boundaries of her own independence. “What did I have to forfeit?” she states. “I was destined to die regardless.” In 2016, Coppola became, as she mentions, the most senior woman to helm her initial feature film, the romantic comedy “Paris Can Wait.” (In 2020, at age eighty-four, she followed it with the movie “Love Is Love Is Love.”) Nevertheless, these quantifiable accomplishments weren’t the singular indicators of her newfound autonomy. The book itself is a compact cri de coeur, energized by Coppola’s fortitude—by her dedication to charting the perimeters of her personal sphere, through writing.

When her tumor is initially detected, one of Coppola’s physicians informs her that it’s “the size of a sizeable lemon”—the botanical metaphor flourishing within the harsher, more precise framework of Coppola’s life-or-death predicament. This is accurate, too, of her depictions of nature, which populate the book. In a diary entry from 2018, she recounts that she has decided to remain behind on the family estate, in Napa, while Francis and the rest of the Coppolas embark on a journey to New Orleans, a determination that “Francis was exceptionally irritated with,” she writes, since “he firmly believes my proper place is alongside him.” And yet Coppola remains steadfast in her decision, and “almost exuberant in [her] solitude.” She gazes out the window on a “sunny, frigid winter day,” observing the “contorted 200-year-old oak tree” with three bird feeders that she notices are empty. “Two redheaded woodpeckers are perched expectantly on a limb as if awaiting their provider. Small finches and sparrows flit about in disappointment,” she writes. “I’m certain they are well, as nature is profuse all around: lush green grasses, shrubs with scarlet berries, mosses, oaks, and bay trees abound. Just as the family is flourishing in New Orleans without me.” ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com