Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Back in 2012, some years before her husband, Donald Trump, was elected President of the United States, Melania Trump tweeted a picture of a beluga whale, its glistening white head emerging from the water, its toothy maw open in a half grin. “What is she thinking?” the Slovenian-born onetime model captioned the image. Over the past decade-plus, this tweet, which at last count has been reposted forty-seven thousand times and has garnered fifty-eight thousand likes, has emerged and reëmerged periodically in my feed. On its own, it already had high meme potential—there’s just something inherently funny about a person wondering publicly, apropos of nothing, as to the inner reflections of a stock-image marine mammal (and deciding, too, that this stock-image marine mammal is a girl). But the fact that it was Melania Trump who had posted the tweet made the whole thing even more intriguing, since the question she posed could pertain not just to the beluga but also to herself.

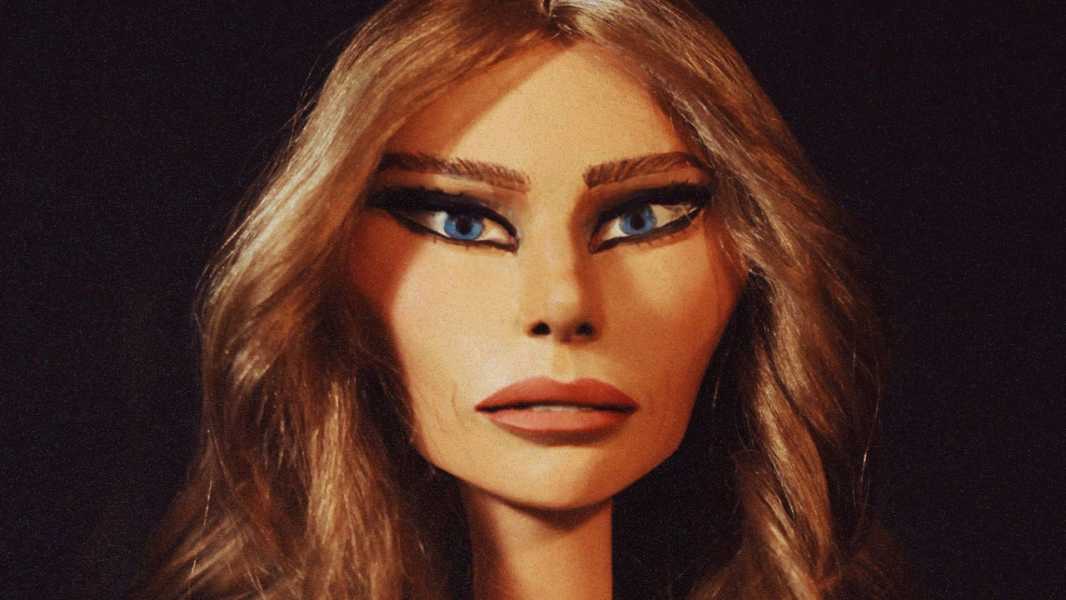

A feline-eyed, high-cheekboned beauty, whose sleek good looks were giving Instagram face long before Juvéderm was even a twinkle in Kylie Jenner’s derm’s syringe, Melania has been an enigma ever since she came to public attention, in the late nineteen-nineties, when she began dating Trump. (At the time of their meeting, he was fifty-two and she twenty-eight.) For Melania, the beluga tweet was an outlier, a rare expression of quirk. As a rule, she has existed in the collective imagination not so much as real-life woman, with her own interests and idiosyncrasies, but as a glossy 2-D image, largely known through the mediating scrim of magazine coverage, which has tended to present her as one luxury object among others in her mogul husband’s arsenal. (In 2004, before her wedding, Vogue followed her to Paris to shop for a couture gown for the ceremony, and then put her on its February, 2005, cover with the words “Donald Trump’s New Bride: The Ring, The Dress, The Wedding, The Jet, The Party”; a year later, when she was heavily pregnant with her son, Barron, the publication once again featured her, this time in an Annie Leibovitz spread, posing in a gold bikini and stilettos on a plane’s airstairs in Palm Beach, as Trump idled in a silver McLaren on the tarmac below her.)

Even after Trump became President, Melania remained an essentially unknowable text. Of course, all actors in the political arena depend on some level of obfuscation, and an attempt to figure out what a public figure really thinks tends to be a fool’s errand. And yet, historically, the role of First Lady has depended on a kind of approachable legibility—a cheerful, open-bookish willingness to soften the hard edges that the role of President demands, through displays of helpmeet-like keenness. Melania, with her pronounced Cold War accent, snugly streamlined outfits, and reluctance to discuss personal matters, seemed more sexy Bond spy than traditional First Lady. During Trump’s Presidency, she didn’t speak publicly very often—“There is absolutely no question that she has been quieter than any modern First Lady we’ve known,” the Washington Post’s Mary Jordan, who has written a biography of Melania, said, in 2020—and even when she did make a rare address, such as the speech she gave at the 2016 Republican National Convention, some of her words were revealed to have been lifted from Michelle Obama.

What was Melania thinking? The silent vacuum of her personality—which stood in stark opposition to her husband’s endless bloviating—naturally led to a media rush to fill it with Kremlinology. Her every move and gesture were analyzed: that time on a visit to Israel, in May, 2017, when Trump attempted to grab her hand while walking down a red carpet with Sara and Bibi Netanyahu, and she swatted his hand away; or when, in June of 2018, on the way to and from a visit to a shelter for migrant children at the U.S.-Mexico border, she wore a jacket whose back was emblazoned with the words “I REALLY DON’T CARE DO U?”; or when, to cap the same year off with a bang, she decorated the White House with blood-red, Goth-style Christmas trees.

Her new memoir, “Melania,” the former First Lady proposes, is a “deeply personal and reflective” corrective to the mainstream media’s unfair and malicious misreading of her actions, intentions, and very character. “As a private person who has often been the subject of public scrutiny and misrepresentation, I feel a responsibility to set the record straight and to provide the actual account of my experiences,” she writes, in the book’s opening note. And yet, despite this scintillating promise to draw back the drapery and expose “the woman behind the public persona,” “Melania” is one of the flattest, most abstract, and least revealing accounts of a life that I’ve probably ever read.

The basic armature of Melania’s story has long been known, and she recounts it here again. She was born in 1970, in Slovenia, to a tight-knit family. Her mother was a patternmaker and her father an auto-industry entrepreneur, and she grew up in relative comfort with her older sister, Ines, in the bucolic town of Sevnica. She was scouted as a model in her teens and lived and worked in Italy and France before moving, at twenty-six, to New York, where she continued to pursue her career. In 1998, she met Trump at a night club, and the two began seeing each other; they married in 2005, and welcomed one son, Barron, a year later. In the decade that followed, before Trump became President, she kept herself busy with motherhood while also selling a jewelry line on QVC and developing skin-care products. Later, she followed her husband to the White House and beyond it, as the country experienced unprecedented events, including the Black Lives Matter movement, the COVID pandemic, the January 6th insurrection, and Trump’s first assassination attempt. (The Stormy Daniels trial is not mentioned.)

I realize that the above makes some fascinating and exceptional episodes seem quite dull, but what if I told you that Melania’s much lengthier account adds almost nothing of note or interest to the bare bones of this précis? The writing is riddled with generalities and clichés, at a level I haven’t seen since teaching college-freshman comp in the early twenty-tens. “Visiting museums is a habit I have maintained in every city I’ve lived in. They bring me joy and inspiration,” Melania writes, of her cultural interests. Of arriving in N.Y.C.: “New York City was a vibrant and sophisticated playground. Memorable dinners at Cipriani with friends and fellow models were a social highlight.” Of motherhood: “The experience . . . has been a profound learning process, one that has shaped me in ways I never could have imagined.” Of advancing her modeling career: “The path to success may not always be easy, but with determination and courage, you can achieve your dreams.” (As I read, I kept flashing back to scrawling “How so??” and “Example plz!!” for the hundredth time in the margins of a student paper, the tip of my pencil threatening to go clear through the page in barely suppressed agitation.)

In matters of political import, Melania gives us not much. For a woman who has been a close witness to some of this century’s most high-stakes world events, she has little to say about them and is either unwilling or unable to provide a view from within the inner sanctum. Occasionally, she slips in some words about “the media, Big Tech, and the deep state” and their attempts to slander the Trumps because of politics, or shares that she, much like “many Americans,” has “doubts about the [2020] election to this day.” She also discusses her efforts in matters of child welfare, including claiming that she pressured Trump to stop the family-separation policy at the border—the “I REALLY DON’T CARE” jacket, she writes, wasn’t a statement about child migrants but about the media—and her Be Best anti-cyberbullying and wellness initiative. But, as someone who has “long upheld the value of traditional gender roles,” she seems to mostly hew to a separate-spheres ideology, and we get relatively little information of public significance. (Concerning her husband’s political achievements, she suggests, quite vaguely, that America “had made astonishing progress” during his Presidency.)

Now, I’m the last person who’d complain about anyone who prefers to tarry with the seemingly insignificant private sphere, but Melania doesn’t offer any details that would make such a choice worthwhile. Instead, we get endless passages in which she tediously describes her encounters with heads of state and their wives, in the context of overseas visits and state dinners, or, in the case of the Obamas, during the transition process. Melania’s first conversation with Michelle Obama was “cordial and pleasant,” and the second “pleasant and lighthearted”; while visiting London, “it was an absolute pleasure to reconnect with [Prince Charles]”; and, while visiting Tel Aviv, it was “a pleasure to reconnect with Bibi and Sara.” (And that swat of Trump’s hand on the tarmac, to settle that matter, wasn’t a swat at all, but simply a way to signal to her husband that the two couples couldn’t walk four abreast on the red carpet.) Sometimes, it appears as if she has simply run out of ways to describe her total and inexplicable delight at her various encounters, and a glitch happens, as in the case of Brigitte Macron. “Our interactions were enjoyable and we were always glad to see each other,” she begins, blandly. And then, suddenly, and with no further elaboration: “Together, we embraced the unknown, turning every moment into an exciting adventure.” (What?)

Much has been made in the run-up to the memoir’s publication of the former First Lady’s pro-choice stance. (“A woman’s fundamental right of individual liberty, to her own life, grants her the authority to terminate her pregnancy if she wishes,” she writes.) While I find her words on abortion commendable, it might be the only surprising contribution that “Melania” makes, and the fact that the passage was advertised in advance reads to me as a promotional smoke screen, to distract from the book’s more general emptiness. And, speaking of emptiness, Melania’s efforts to prove the robustness of her relationship with her husband are not entirely compelling, either. After Trump wins the election, the pair have “a private moment”:

“Congratulations,” I said. “What an achievement. All those other people . . . and you won. You’re the president of the United States of America.”

“And you’re the First Lady,” he said. “Good luck.” I looked at him, momentarily unsure of his meaning. Good luck? I realized he wasn’t worried, he was proudly confident I could handle the future. It was his unique way of saying, “Good luck—I know you’ll excel. Let’s get started.”

Donald had always placed a considerable amount of trust in me—as a wife, mother, confidante, and adviser. That morning his trust felt particularly tender and profound, resonating with love and understanding of our future together. I was grateful for that moment before we would inevitably be pulled in myriad directions once more.

As my eyes scanned this passage, it struck me that just as we, the readers, attempt to squeeze meaning and feeling from Melania’s account of her life, so has she been attempting to squeeze meaning and feeling from her husband, a man so cold that, as his onetime mentor Roy Cohn famously said, he “pisses ice water.” Never has so much stress been put on the words “good luck.” I found the moment strangely poignant. Suddenly it made sense why it might be easier to live an almost entirely abstracted life. Poor Melania. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com