On May 9, 1966, the South African photographer Ernest Cole left Johannesburg for Europe, using a passport he’d secured under the pretext of making a pilgrimage to Lourdes. He’d sent a cache of his contact sheets out of the country two weeks earlier with the journalist Joseph Lelyveld. Other negatives and prints were left behind in the care of friends, to be mailed or smuggled out later. His images showed Black life under the edicts of apartheid, and they’d made him a target of the South African regime. As early as 1963, Cole had appeared in intelligence reports for his links to a newspaper with ties to the Communist Party. Later, police intercepted correspondence that he had exchanged with a potential publisher in New York. After leaving the country, Cole passed through London, Paris, Copenhagen, and Hamburg before arriving in New York, in September of 1966, where Magnum’s bureau chief sold his photos to Life and negotiated the release of a book, titled “House of Bondage.” When it came out, in 1967, the South African government took notice. In recently declassified documents, a security official noted that “even the self-confessed Communists are not having as much success with agitations against us as Cole has achieved now.” In 1968, the twenty-eight-year-old Cole was the youngest person to appear on the country’s list of banned individuals that year. He would remain in exile for the rest of his life.

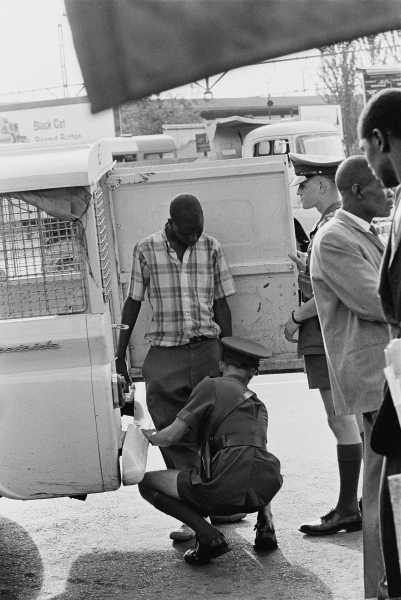

Sometimes checks broaden into searches of a Black man’s person and belongings.

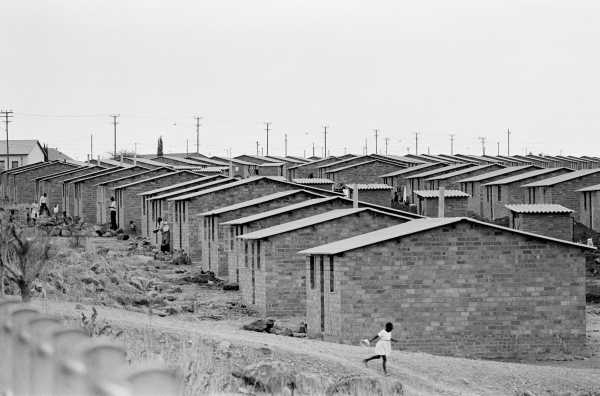

Acres of identical four-room houses lining nameless streets. Many are hours by train from city jobs.

At middle-class marriages, rented cars act as status symbols. An expensive wedding can leave a couple in debt for a year.

Cole was born Ernest Levi Tsoloane Kole in the freehold township of Eersterust, on the outskirts of Pretoria, to a father who worked as a tailor and a mother who was a washerwoman. He discovered photography at the age of eight and in his teens created a darkroom in his home and charged subjects for small prints he took with a box camera. He found early employment as a messenger, a clerk, and a darkroom assistant, and then as a photographer for the Bantu World, the largest daily newspaper in Johannesburg catered toward a Black African audience. “House of Bondage”—which fell out of print in the eighties and is now being republished by Aperture—provided audiences outside of South Africa with their first visceral view of apartheid. In the United States, it sold out in less than a year. Cole had also been commissioned by the Ford Foundation to photograph the Black experience in the rural South and urban North—a “House of Bondage” for America—but, for reasons unknown at the time, he never handed in the images, and they were never published. By the late seventies he’d seemingly abandoned photography. He intermittently fell into homelessness, and portions of his archive were lost or auctioned off. He died, of pancreatic cancer, in 1990, one week after Nelson Mandela was released from prison.

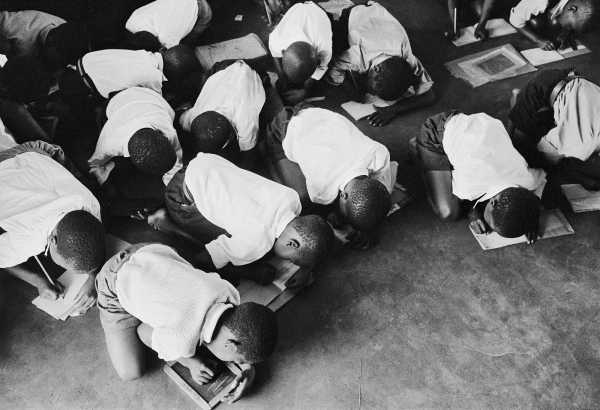

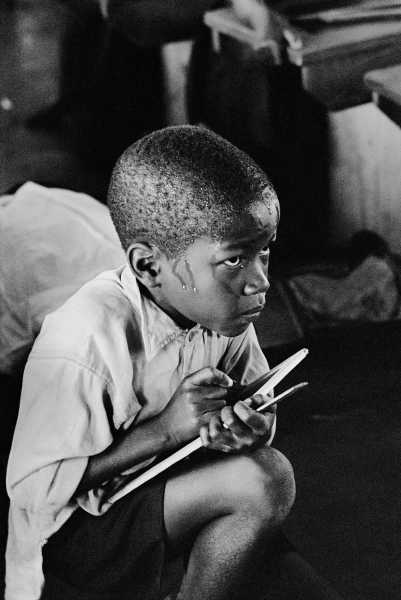

Students kneel on the floor to write.

In “House of Bondage,” South Africa is a country of queues, signs, and papers—the bureaucratic instruments through which Black life was brutalized. The violence embedded in the system subsumes Cole’s subjects, whether they’re in their homes and schools, in streets and hospitals, or in the mines where labor is cheap and the nude Black male body is marched through doctors’ offices, examined, and labelled with wrist tags. The police arrest anyone for arbitrary offenses related to their pass books, which denote whether or not they’re permitted to walk in a white urban area. The wait times for treatment at clinics designated for Black Africans prolong suffering, with patients often dying before they reach beds crawling with infection.

During group medical examinations, nude men are herded through a string of doctors’ offices.

In an essay for the book, the journalist and scholar James Sanders calls Cole a “fluid, mercurial” figure, who was adept at circumventing the red tape of apartheid. In the early sixties, after Eersterust was marked for demolition and designated a “Colored” area, Cole successfully secured reclassification as “Colored,” rather than “Black,” allowing him to move freely without a pass book. It is said that he managed to take pictures inside the mines by hiding his camera in a sandwich bag. Likewise, he refuses to portray his subjects in a state of “static victimhood,” as the curator Oluremi C. Onabanjo writes; the figures in his photographs are often in motion, their blurred silhouettes attesting to the possibility of a Black life that cannot be contained by apartheid—as in the cover image of commuters clinging to the outside of a crowded train as it hurdles ahead. Tsotsis, youths who have turned to pickpocketing rather than working for inadequate wages in menial jobs, appear as transient figures, dandily clad in blazers and felt hats, and move in groups to distract their targets before escaping to evade arrest.

Police try to solve the tsotsi problem with roundups and arrests. These measures only toughen the youth, who take pride in being able to stand up to interrogation, beatings, and jail conditions.

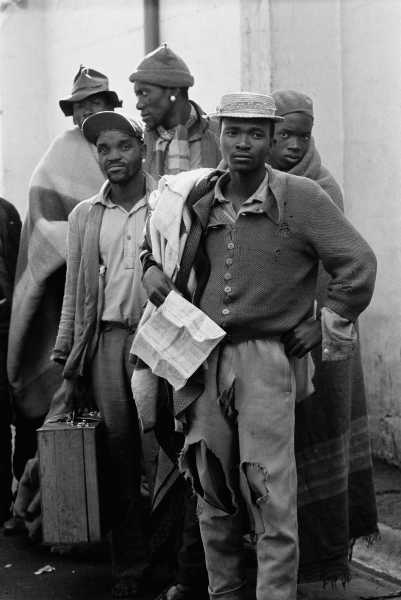

Pensive tribesmen, newly recruited to mine labor, await processing and assignment.

An earnest boy squats on his haunches and strains to follow a lesson in the heat of a packed classroom.

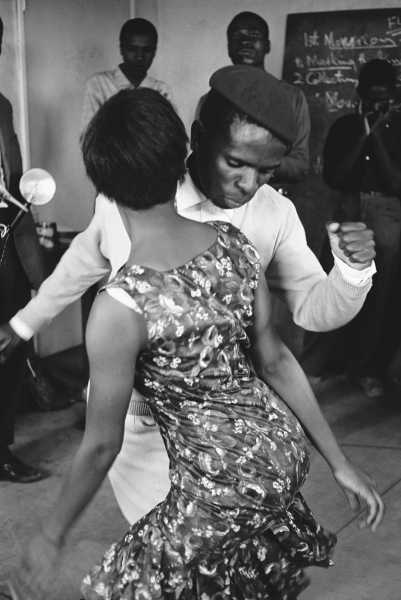

Cole is attuned to the resoluteness that grows out of the daily traumas of apartheid, the refusal to bend to drudgery, or to horror. In one image, a schoolboy squats on his haunches in an overcrowded segregated classroom, beads of sweat streaming down his face as he intently grips a pencil and a slate in his small hands, following along with the teacher’s lesson. In another image, a woman who had been fired from her job as a maid twice is spectacularly turned out in a striped skirt and matching blazer. The reason for her dismissal, we learn from Cole’s caption, was being too chic. Elsewhere, Cole takes his camera into the neighborhood shebeens: privately run speakeasies that first opened in response to earlier prohibitions on African drinking. There, men and women indulge freely, swaying to music provided by the guitar of a fellow-patron, and then bury their liquor in the ground to hide it from the police.

Untitled, South Africa, c. nineteen-sixties.

Untitled, South Africa, c. nineteen-sixties.

In 2017, a cache of Cole’s lost work, including unpublished material believed to be from his Ford Foundation assignment, resurfaced in safe-deposit boxes at the Skandinaviska Enskilda Banken, in Stockholm. A new section of “House of Bondage,” titled “Black Ingenuity,” includes unseen images from South Africa depicting what Cole described, on a folder where he stashed the negatives, as “remnants of everything, of joy, of peace and harmony, of culture, of creativity, and of all the things they failed to stamp out.” These include scenes from an arts space called the Dorkay House, where actors and dancers shimmy during a rehearsal, and images from the 1964 Castle Lager Jazz Festival in Johannesburg, where a band plays to a jubilant crowd. One series of photographs shows athletes flexing their muscles and applying oil to their bodies while others participate in a boxing match attended by a crowd of Black spectators. Here, the young men are not herded and paraded, stripped naked and examined for their utility as cheap labor. They are unyielding in their poses, their bodies belonging fully to them.

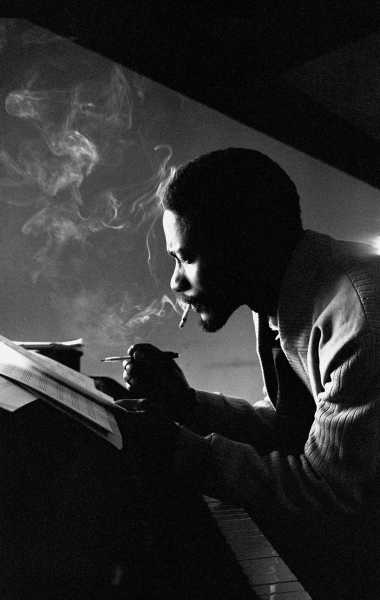

In three images that form a part of the new chapter, Cole photographs a young pianist hunched over sheets of music, in the act of writing a new composition. An expression of intense focus in the first photo gives way, by the third, to one of satisfaction. The pianist holds his mouth slightly agape, perhaps humming the tune he has invented. The plume from his cigarette floats upward out of the frame, and the light hits his eyes just so. All that matters is the beauty of this quiet act of defiance, this small moment of creation—the creation of a melody but also of a photograph, which Cole insured would one day be seen.

Untitled, South Africa.

Sourse: newyorker.com