Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

In 2008, my wife and I asked a friend to read a passage from Cormac McCarthy at our wedding, in England. We may be the only fools in the world ever to have done so. McCarthy’s work—depicting a cold and violent America in prose that is by turns austere, gaudy, religiose, archaic—does not easily lend itself to such a joyful occasion. But I was and remain a McCarthy nut, and “All the Pretty Horses” was a book we both adored. In the wedding reading, John Grady Cole, the novel’s hardy teen-age hero, is attempting to persuade his lover, Alejandra, to defy her family, and to live with him:

She took his hand and held it in hers and touched the veins. They went out in the dawn in the city and walked in the streets. They spoke to the streetsweepers and to women opening the small shops, washing the steps. They ate in a cafe and walked in the little paseos and callejones where old vendresses of sweets, melcochas and charamuscas, were setting out their wares on the cobbles and he bought strawberries for her from a boy who weighed them in a small brass balance and twisted up a paper alcatraz to pour them into. They walked in the old Jardín Independencia where high above them stood a white stone angel with one broken wing. From her stone wrists dangled the broken chains of the manacles she wore. He counted in his heart the hours until the train would come again from the south which when it pulled out for Torreón would either take her or would not take her and he told her that if she would trust her life into his care he would never fail her or abandon her and that he would love her until he died and she said that she believed him.

(In a story about entrapment and escape, the “paper alcatraz” is the detail that wounds me.)

The man who read this in the church, Chris Craig, flew helicopters with my father in the Fleet Air Arm. He took special care to stay in touch with our family after my dad died in a flying accident, in 1982. With me, that care often took the form of letters, at the end of which he would sometimes recommend books or films. I loved getting those letters. In a box somewhere in my house I still have the note he sent me when I was eighteen years old, advocating strongly for Cormac McCarthy in loopy blue cursive, on his favored blue writing paper.

What a gift that recommendation was. Later that year, in 1998, I read “All the Pretty Horses” on a daylong train journey that passed through rural Croatia. Looking out the window at the reddish scrubland, I imagined myself in the world of the novel: a bildungsroman in which two boys ride out from Texas into Mexico and learn about horses, love, violence, and the nastiness of the adult world. I had never experienced anything like “All the Pretty Horses.” None of the characters told you what they were thinking. Action and description were everything. And yet the novel appeared to contain vast philosophies I couldn’t yet name, but whose significance seemed self-evident. I was hungry for more.

Soon afterward, I swallowed the œuvre: McCarthy’s profoundly bleak early Southern novels, and his violent Gnostic masterpiece “Blood Meridian” (1985). When they appeared in the mid-aughts, I gobbled up “No Country for Old Men” (2005) and, less hungrily, “The Road” (2006). But it was the Border Trilogy that captured me first. After “All the Pretty Horses,” I quickly read “The Crossing” (1994), in which Billy Parham embarks on a journey with a wolf, and then “Cities of the Plain” (1998), which unites the heroes of the first two novels. The trilogy concerns boys learning to live as and with men—and now it’s easy to see why such stories would have gripped me when I first encountered them. They are all, also, novels that inquire about the act of storytelling itself. When I read them as a writer-in-chrysalis, it was these aspects that resonated.

Looking back through my battered British Picadors, I’m struck again by those moments of narration within the trilogy. Toward the end of “All the Pretty Horses,” John Grady Cole encounters a group of kids, and shares his lunch with them. They ask him a few questions. Where does he live? Where is he going? Each answer leads to more inquiries. He eventually tells them it would take too long to explain everything:

Es una historia larga, he said.

Hay tiempo, they said.

He smiled and looked at them and as there was indeed time he told them all that had happened. He told them how they had come from another country, two young horsemen riding their horses, and that they had met with a third who had no money nor food to eat nor scarcely clothes to cover himself and that he had come to ride with them and share with them in all they had. . . .

Hay tiempo. But then, in the space of a paragraph, John Grady Cole narrates the entire plot of “All The Pretty Horses.” In another writer’s hands, this tale-within-a-tale might have been an arch, postmodern device. But not in McCarthy. In his universe, a narrative is the thing itself. His characters pass stories between one another like parcels.

Another favorite passage, from “The Crossing”: Billy Parham meets a blind man and his female companion. The two strangers tell Billy a long, baroque, and gruesome tale about how the man lost his eyes at the hands of soldiers. Partway through, Billy asks if the story’s true. Of course it’s true, the blind man says. But Billy won’t let it go:

Billy asked how it could be that on the long road to Parral he should meet only three people but the blind man said that he did meet other people on that road and that he received from them many kindnesses but that the three strangers at issue were those with whom he spoke of his blindness and that they must therefore be the principals in a cuento whose hero was a blind man, whose subject was sight. Verdad?

Stories, in McCarthy, can at once be oceanic—Judge Holden, in “Blood Meridian,” says, “The universe is no narrow thing”—and fit into a thimble. I find it helpful to think of the blind man’s wisdom when I’m editing. Characters can be excised, incidents expunged, if they do not serve. What remains is only what is essential.

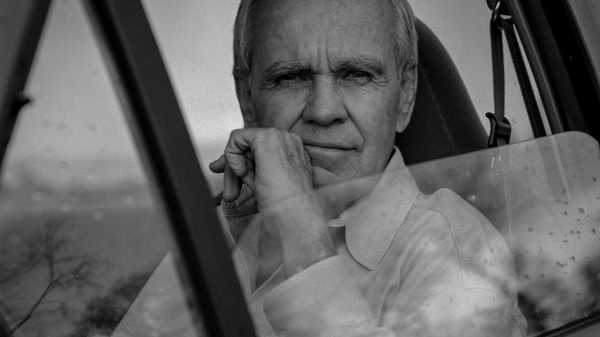

The act of writing was its own reward for McCarthy. In a long career, he gave few interviews, and rarely explained himself. He didn’t make himself known. I can’t say that I love everything he wrote. Sometimes, when his prose enters the Biblical register, I find myself baffled and unmoved. Neither am I a completist. I resisted reading the last two novels, “The Passenger” and “Stella Maris,” both published last year, for fear of denting my appreciation of the earlier ones. I wonder why, then, on hearing the news of his death last night, I found myself momentarily overcome. Perhaps because I met McCarthy first in a peculiarly receptive period, and perhaps because the provenance of my relationship with his writing leads me back through the decades of my own life. And perhaps because, looking again in the old books, I find so much pleasure in the authority of his voice, and the wisdom that flames out from his pages, and it is painful to imagine that such a fire has been extinguished.

The novels themselves provide comfort, after a fashion. Within the blind man’s story there is another. A girl meets a gravedigger, or sepulturero. Unlike in “Hamlet,” there is no badinage between the two, but as in Shakespeare the sexton has truths to impart:

It was the nature of his profession that his experience with death should be greater than for most and he said that while it was true that time heals bereavement it does so only at the cost of the slow extinction of those loved ones from the heart’s memory which is the sole place of their abode then or now. Faces fade, voices dim. Seize them back, whispered the sepulturero. Speak with them. Call their names. Do this and do not let sorrow die for it is the sweetening of every gift. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com