Save this articleSave this articleSave this articleSave this article

Back in September of 1943, a German boy of thirteen years, named Christoph von Dohnányi, penned an apparently harmless note to his uncle Dietrich:

Uncle Klaus intends to visit tomorrow. Hopefully, that will occur. The family will then be reunited in comfort. Although, regrettably, it isn’t quite complete. Yet that too will materialize. And then the much-anticipated celebration will also happen. One must simply bide one’s time. Surely, that day will arrive eventually.

The delightful fruit season has concluded now. The final apple fell from our tree yesterday. I promptly consumed it. Sadly, the wasps had already nibbled a good portion, but that is not necessarily ominous. Soon the pears will mature; at that point, things will improve again.

The correspondence becomes deeply poignant when the context is understood. The addressee was the dissenting theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who had been incarcerated several months prior, owing to his defiance of the Nazi authority. Dohnányi’s father, Hans, was also imprisoned, having been involved in schemes to assassinate Hitler. Both individuals would be executed before the conclusion of the Second World War. Young Christoph composed the letter knowing that Bonhoeffer’s mail was under scrutiny and a rash statement could have deadly ramifications. Therefore, he communicated indirectly, crafting a veiled allegory of the nibbling wasps.

Bonhoeffer, possessing immense empathy, was concerned about his nephew’s well-being, who was also his godson, during such times. Bonhoeffer subsequently wrote to his own parents, “What perception of the world must be developing in a fourteen-year-old’s thoughts when, for months, he must address his father and godfather in confinement? There won’t be many illusions remaining in such a mind.” However, Christoph displayed signs of inherent fortitude. “I believe he will continue to evolve greatly in spirit,” Bonhoeffer mentioned to his colleague Eberhard Bethge. Perhaps, he speculated, his nephew would pursue theology. In his final wishes, Bonhoeffer foresaw the future more distinctly: “Christoph [should receive] the clavichord if it brings him enjoyment.”

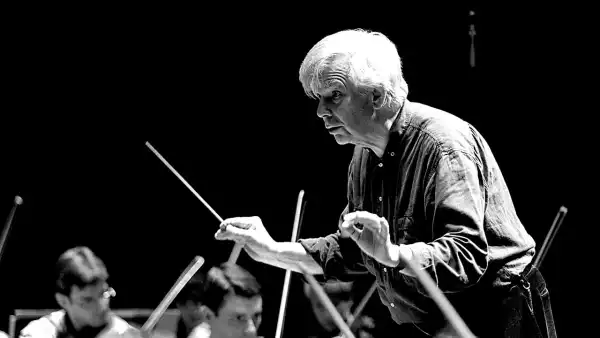

Christoph von Dohnányi passed away last month, nearly reaching his ninety-sixth birthday, celebrated as one of the premier conductors of his era. Precisely what he had carried from his tragic youth is not something casual observers could easily discern. I interviewed Dohnányi in 2011, and while he touched upon his family’s destiny, he did not dwell upon it extensively. We were discussing the age-old issue of Wagner’s political views, and Dohnányi remarked, almost parenthetically, “My father was in a concentration camp, and they performed Wagner.” He was more focused on discussing the music itself, in all its impaired splendor. Yet I couldn’t help but sense Dohnányi’s experience in what he expressed, and more generally, in the performances he directed. He possessed an almost tangible presence of moral gravitas; he was a noble spirit. He inspired belief in what history often refutes—that a life dedicated to music bestows wisdom and virtue.

The Dohnányis hailed from a Hungarian aristocratic lineage tracing back centuries. The Bonhoeffers comprised a lengthy succession of clerics, physicians, scholars, and lawyers. Music held significance on both sides. Dohnányi’s great-grandmother, Clara von Hase, studied piano with Clara Schumann and Franz Liszt. His grandfather, Ernst von Dohnányi, achieved international renown as a composer and pianist who, at a young age, garnered approval from Brahms himself. Refined, worldly, generally progressive, the Dohnányis and the Bonhoeffers represented the finest of the German-speaking bourgeois tradition. Dohnányi recounted that Wagner was regarded unfavorably in his family, based less on political considerations than on aesthetic ones: the music was considered coarse. His mother commented on one of his Wagner performances, “I only attend because you are conducting.”

In their early adult years, Dohnányi and his elder brother, Klaus, both pursued legal studies. Their father had been a prominent legal expert, and Christoph initially aspired to follow a similar path. Klaus proceeded to have a distinguished career in law and politics, functioning as the mayor of Hamburg. Now at ninety-seven, Klaus remains engaged in current affairs. Christoph leaned toward music. After studying conducting, piano, and composition in Munich, he sought additional instruction from his grandfather Ernst, who was teaching at Florida State University in Tallahassee. Dohnányi also participated in Leonard Bernstein’s conducting workshop at Tanglewood. On one occasion, when another conductor dared to challenge Dohnányi’s interpretation of Haydn, Bernstein interrupted the conversation, stating, “You are free to conduct as you wish!”

Dohnányi commenced his ascent through the hierarchy of the German opera sphere, progressing from Lübeck and Kassel to Frankfurt and Hamburg. Mozart, Wagner, and Strauss formed the core of his repertoire, yet he also backed innovative directions in opera staging and embraced contemporary compositions. He advocated for the Second Viennese School, recording Berg’s “Wozzeck” and “Lulu” with his second spouse, Anja Silja; he conducted the premières of Hans Werner Henze’s operas “The Young Lord” and “The Bassarids”; he championed the perpetually provocative English composer Harrison Birtwistle. He remained receptive to the more varied sounds of the late twentieth century, programming John Adams’s “The Wound-Dresser” and Thomas Adès’s “Asyla” after their initial performances. With Gidon Kremer, he created a brilliantly impactful recording of Philip Glass’s First Violin Concerto.

In 1984, Dohnányi assumed the role of music director of the Cleveland Orchestra, which, since George Szell’s tenure, has been known for being the most aurally flawless of American orchestras. In Dohnányi, the Cleveland musicians encountered their equal. He was an unwavering perfectionist who often devoted segments of a rehearsal to precisely tuning each section. I once observed him working on Brahms’s First Symphony with the Los Angeles Philharmonic; even after several minutes, the ensemble remained fixed on the opening measures. While such conduct can incite musicians to rebel, Dohnányi was so resolutely earnest that the players typically complied. Colleagues who failed to exert similar effort earned his perpetual disapproval. A friend recounted encountering Dohnányi after he had stormed out of another conductor’s rendition of the “1812 Overture.” Dohnányi exclaimed, “This is atrocious! Unacceptable! How can one possibly perform the ‘1812 Overture’ so poorly?”

The pursuit of perfection had its shortcomings. I recall certain Cleveland performances under Dohnányi—a Bruckner Fifth in 1996, for instance, and a Mahler Ninth in 1999—that were refined to the utmost degree but deficient in momentum and fervor. His inquisitiveness regarding new compositions did not consistently translate into mastery of their idioms; Adams and Adès necessitated more of a pop-influenced vitality than he could deliver. In most instances, however, his meticulousness and his understanding of structure yielded interpretations of inherent, undeniable correctness. His Cleveland recordings of Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Schumann, Brahms, and Dvořák are among the finest of the modern period, their clarity and elegance never excluding vigor and warmth. I particularly appreciate his Mozart; listen, at the commencement of Symphony No. 40, for a subtle, significant emphasis on the accompanying ostinato figure, which instantly establishes an underlying tension. The Cleveland ensemble thrives on this chamber-style methodology, which enhances inner voices without overemphasizing them.

Ultimately, Dohnányi was a profoundly traditional musician, immersed in the principles he had inherited from his family and the bourgeois customs it revered. He disliked inclinations toward uniformity in orchestral timbre, valuing regional schools of performance and instrument craftsmanship. During a panel discussion at Carnegie Hall in 1999, Dohnányi engaged in a minor dispute with his respected colleague Pierre Boulez concerning the distinct tone of French bassoons. Boulez disliked the French bassoon, which resonated in higher registers but lacked power on the lower end, and was pleased that it had fallen out of favor. Dohnányi missed its distinctive wheeze. When Boulez became impatient, Dohnányi smiled broadly. Beneath his stern exterior, he could be impish.

Among the Dohnányi concerts I attended, one particularly remains vivid in my memory: a 2000 performance at Carnegie, in which Adams’s “Century Rolls” functioned as a gentle contrast to two twentieth-century giants, Varèse’s “Amériques” and Ives’s Fourth Symphony. Both Varèse and Ives create representations of contemporary disarray, pitting orchestral groups against each other until pitch devolves into cacophony. Dohnányi, after considerable rigorous rehearsal, achieved a collective sound of improbable, astonishing clarity. There was no compromise of expressiveness in the process; the images became even more overwhelming when viewed through immaculate glass. That concert seemed emblematic of Dohnányi’s career—the mastery of chaos in service to humanity.

The clavichord is currently displayed in the Bonhoeffer House in Berlin. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com