Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

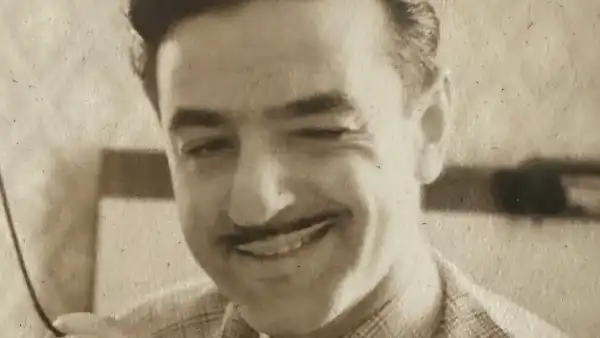

A handsome young fellow, relaxing on a bed inside his Brooklyn abode, is snapping a selfie. Clearly, he’s gone all out. An antiquated plate camera is perched upon a tripod. A mirror has been positioned. His inky locks are sharply cut into a dapper style. His mustache is meticulously groomed. He is clad in a ribbed, white, sleeveless tank top.

He is jokingly posing for the lens yet endeavors to appear composed, hoping to provoke a response. He hails from Williamsburg. He is the embodiment of our collective imagination about the district since its resurgence around the start of this millennium, changing from a run-down tenement area to the present-day post-hipster, mock-bohemian haven.

However, this young man doesn’t belong to that Williamsburg. He is from the old one. He’s capturing this image in 1935. I’m aware of this as he is my grandfather, Eli Fuchs, and positioned to his left is the bassinet containing his infant daughter, Lola, who is my mother.

During a recent visit at my mother’s home in New Jersey, while sifting through some aged cartons, I was shocked to come across numerous selfies snapped by her father during the nineteen-thirties and forties: humorous ones, serious ones, clearly alluring ones. Eli was an introverted, unassuming person in my recollection—a former employee of the U.S. government. For the majority of his working life, he was employed at the Raritan Arsenal, located in Middlesex County, where he designed, illustrated, and supervised the printing of posters, guides, and pamphlets for the United States Army.

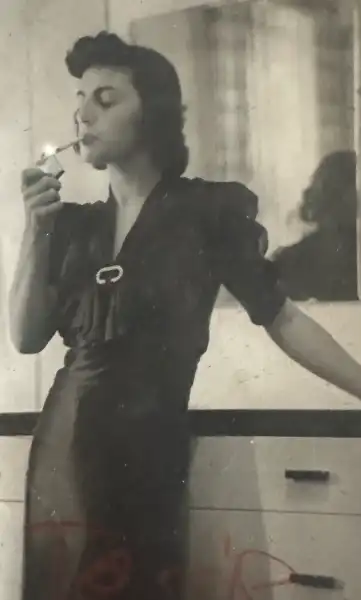

I was not unaware of his artistic inclinations. Eli possessed talent as an amateur photographer and artist. I own an oil painting he created of me at roughly age eight, its stately medium offset by the fact that I’m donning a silly white nineteen-seventies T-shirt featuring red trim. And, at times, Eli was somewhat mischievous. He subscribed to Playboy magazine, leaving issues prominently displayed for his grandkids. I have also come to learn lately, somewhat to my dismay, that he captured some glamorous and nude shots of my grandmother Tessie during her youth.

Eli Fuchs’s wife, Tessie.

However, his selfies are what truly amaze me. As it happens, we’re at a notable landmark for the art form. Fifteen years past, in June of 2010, Apple released the iPhone 4, its initial iteration to feature a front-facing camera. Though mirror selfies already had a following, now you could refine your expression before pressing the button, or carefully position your phone to conceal the fact that you were the picture taker. Four months later, in October of 2010, a fresh social networking app called Instagram was introduced to Apple’s App Store. This gave the selfie a feeling of instant gratification: your self-image could be posted from your device to a perpetually eager feed. Should you fit a particular archetype, possessing some measure of sway, it could even be turned into currency.

For Eli Fuchs, the selfie did not provide such quickness or a readership. The physical doing of it was no simple feat. In his initial attempts, one can discern that he utilized a mirror to capture his reflection, and undoubtedly, he carefully coordinated his actions in accordance with the light at his disposal. Afterward, he was required to process his film. My mother, now at ninety years old, recalls that, despite the home’s compact size, “he maintained a darkroom equipped with containers containing various solutions. Then, there was the process of drying, with the prints suspended from a clothesline.”

At a certain stage, Eli familiarized himself with the shutter-release cable, enabling him to dispense with the mirror and simply aim the camera at himself. Somewhat later, he obtained a 35-mm. camera, enabling him to shoot outdoors without the burden of transporting his bulky setup: the plate camera, the tripod, along with the black fabric he occasionally draped over his head.

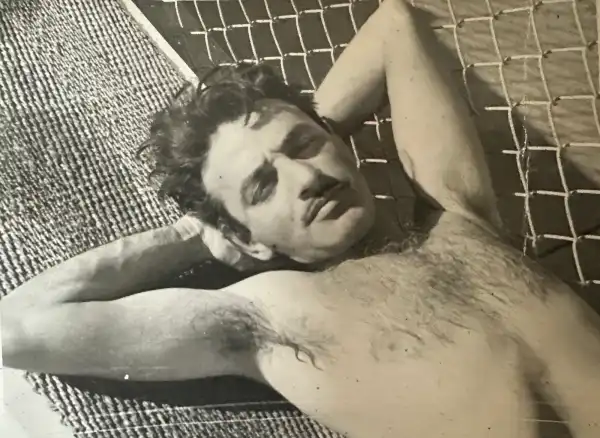

By the nineteen-forties, being in his thirties, Eli clearly possessed enhanced self-assurance about his appearance. In images dating from this period, his slender frame had filled out somewhat, his hair was styled with pomade, and his mustache took on the pencil-thin shape popularized by Clark Gable. The playful posing of his early selfies had ceased. He is posing languidly and shirtless in a hammock. He is looking elegant in a peak-lapel suit accented by a boutonnière. He props an elbow on a low wall, holding himself in a manner suggesting “about the author”. At times, he uses both the shutter-release cable and a mirror—this is evident as he holds the cord while also glancing slightly to the side, scrutinizing his reflection.

Within a specific cord-and-mirror sequence, he is impeccably attired in a plaid oxford shirt accompanied by a tie. He attempts a knowing smile, succeeded by a playful wink. Following this, the shirt is removed, and the stomach is drawn in. As I perused these images, I was stunned to discover that he didn’t always carry out these photo shoots by himself. Occasionally, he had a tiny assistant: my five-year-old mom, who, in one particular image, is positioned behind him in a cap-sleeve dress, adorned with a bow in her hair, depressing the shutter button while he gives a smoldering look toward the mirror, dressed solely in boxer briefs.

What stands out most concerning Eli’s selfies is their likeness to those of today. His purpose, at least regarding these specific photographs, was not artistic. He was not aiming to produce a self-image similar to Rembrandt or Frida Kahlo. He certainly was capable of doing so; positioned on my office wall is a refined ink-wash self-portrait depicting him at his workstation at the Raritan Arsenal, scrutinizing page designs while casually holding a cigarette. Instead, in his photographic selfies, Eli Fuchs was simply a young man from Brooklyn attempting to fabricate a romanticized portrayal of himself—to envision himself as a leading figure.

My mother recalls that he was self-conscious about his “prominent nose.” This term carried just as much meaning back then as it did description. In James T. Farrell’s “Studs Lonigan” set of three novels originating in the nineteen-thirties, set within Chicago’s Irish American South Side, the gruff figures repeatedly refer to Jewish people as “hooknoses,” not to mention “sheenies,” as well as, my favorite, “noodle-soup drinkers.”

On occasion, my mom recounts that she caught Eli studying himself in the looking glass, manipulating his nose this way and that, in an attempt to analog-yassify his face. Following her revelation, I observed that my grandfather took great pains to photograph himself head-on, typically aligning his chin with the device. In only a few images is his head rotated far enough to completely showcase his schnoz in all its Ashkenazi prominence. What could be happening? Was it his intention to separate himself from his parents, struggling immigrants who came from Russia? Were his selfies a means for visualizing himself as a “true” American?

Eli passed away in 1977, when I was a child, leaving me without the chance to directly question him regarding the photos. Nevertheless, Daniel Fuchs, one of his brothers, left some clues. Daniel, older than Eli by three years, was a novelist and screenwriter whose works were greatly valued by Irving Howe and John Updike, the latter of whom commended him as “a poet who never felt the need to strive for a poetic effect, a conjurer who made magic appear remarkably easy” in 1971, via this very magazine. (Daniel also published sixteen short stories inside The New Yorker.)

In more recent times, Daniel has posthumously emerged as a celebrated Brooklyn figure. His prominence rests on three social-realist novels that depicted Jewish tenement life published in the nineteen-thirties: “Summer in Williamsburg,” “Homage to Blenholt,” plus “Low Company.” During their initial release, these literary works sold poorly, yet they eventually garnered recognition upon being re-released as a collection, initially in the sixties and again in the seventies, under the title “The Williamsburg Trilogy.” (We pedants among the Fuchs family note that “Low Company” is actually situated in Brighton Beach.)

Daniel’s commercial failings as a writer compelled him to relocate to Los Angeles to pursue writing for cinema. He realized success, though not monumentally, focusing on crime and heist genres and earning an Academy Award for Best Story on account of “Love Me or Leave Me” (1955), featuring Doris Day portraying the singer Ruth Etting alongside James Cagney as her gangster spouse. As his later years progressed, Daniel published his reflections upon Hollywood together with the lengthy route he’d traveled from the modest locale of Williamsburg. “Within a limited scope of my residence, South Second Street between Hooper and Keap, there existed no fewer than seven movie theaters,” as he noted in the Times during 1971. “The films were exchanged every day or every other day, though I can’t recall which, and nearly all among us, the locally born children, frequently attended the Hooper twice each week, and more than a few of us went even more frequently.”

It’s this fondness for films during both his and Eli’s childhood that provides insight into my grandfather’s mental state. Daniel, in the Times piece, considers the notion that “motion pictures experienced their grand growth thanks to, by a coincidence of events, their emergence just when the immigrant influx had peaked.” However, that was not the true appeal of the cinema, at least not for the Fuchs brothers. “What those images achieved—exhibiting their strength and liveliness, their dominance over life and regularly optimistic pronouncements—acted against the apprehension that engulfed and confined us,” Daniel writes. “That was a vague, inchoate dread which we nearly subconsciously acquired from our parents, fear stemming from Old World oppressions, as a result of the hardships endured within the New World, including the trials which our parents including grandparents had gone through while transporting themselves plus their families through the Old World toward the New—it’s as though the feat of immigration drained their strength and resolve.”

Eli Fuchs’s brother Daniel, an Academy Award-winning screenwriter.

Therefore, for somebody such as Eli, projecting movie-star characteristics, specifically strength and vigor, turned into a pursuit of social advancement, a means for distinguishing himself from the somber reality lived by his foremothers clad in babushkas. As for life’s hardships in the New World? The Fuchs family knew those difficulties. Eli and Daniel were preceded by four more brothers. In 1909, a short time subsequent to when Sara, their mother, gave birth to Daniel, one of those boys, four-year-old George, met his demise after falling while playing atop their tenement’s roof found in the Lower East Side. The position of their apartment had given Jacob, my great-grandfather, a conveniently quick commute to his job—he worked a newsstand situated inside the lobby of the newly erected Whitehall Building, placed upon Battery Place—however, George’s passing caused the family’s relocation to Williamsburg, which, despite its chaos, signified an upgrade compared to the unsafe slum that they’d previously been living inside.

His birth overshadowed by his family’s greatest tragedy, Daniel took comfort in movies and actively transported himself into the fantastical world of Hollywood. He wrote during sun-filled afternoons within the year 1971, recalling his lighthearted days as an inexperienced newcomer, he would wander the lots associated with Warner Bros., taking in “the studio’s accomplished individuals in their finery at their constant performances.” In contrast, Eli’s existence remained ordinary, consistent with that of a professional civil worker who moved his family out of rugged Brooklyn and into suburban Highland Park, New Jersey. As a tinkerer, he took up workspace throughout New Brunswick, positioned across the Raritan River, in which, while off duty, he fabricated gizmos that he anticipated might gain traction, therefore propelling him toward bigger opportunities. One such contraption produced one particular photograph like a sheet comprising fifty stamps each bearing a likeness. He promoted the service within low-budget magazines, going by the identity Stampix. An individual could send a picture of, let’s say, their newborn baby, and, for just one dollar plus a pre-addressed, stamped envelope, get the image back together with fifty miniature adhesive portraits appropriate for baby announcements.

Stampix performed reasonably well yet not remarkably; Eli relinquished the business throughout 1947. The singular unexpected twist regarding his life story is that, in the fifties, he ventured to fix his nose. Yet, that’s less unusual than what actually took place—he invested heavily in rhinoplasty, not simply for himself but furthermore for his partner plus daughter.

My then teenaged mother, whose original nose wasn’t unlike her father’s, had not even articulated a desire for any work to get done. She was a diligent and outdoorsy young woman who proceeded to work like a research scientist at Johnson & Johnson. “My folks were always seeking to make me look better, yet I lacked interest,” she explained to me. “However, I did so in their honor, due to the fact it made them happy.”

The Eli that I came to know exhibited distinction within his appearance, yet I regret not having witnessed within the flesh the nose that troubled him. It feels strange to ponder my grandfather, who kindly guided my siblings and me across the Smithsonian exhibits and took us out to get Baskin-Robbins, as a person possessing the vanity of an influencer. The proof remains in those stacks of pictures. He lived a respectable existence, yet his greatest goals remained dreams, having their most complete realization within the selfies he left.

Sourse: newyorker.com