Whatever reticence a listener might experience with John Coltrane’s “lost album” isn’t musicological but emotional: the spiritual temperature of the music is lower.

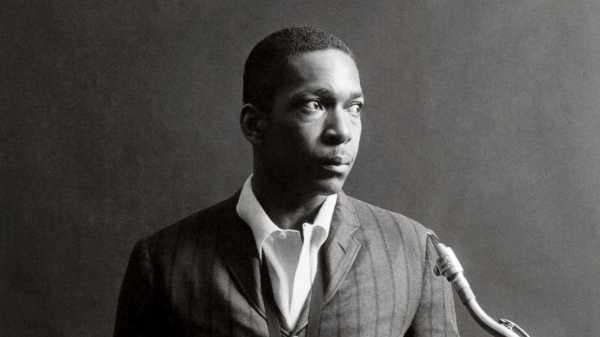

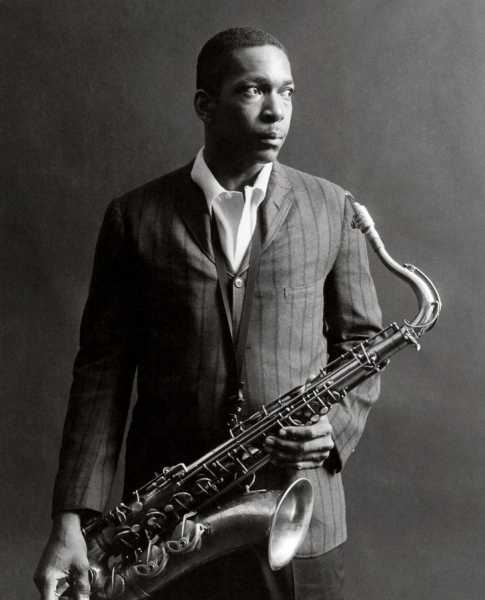

Photograph by Chuck Stewart

It’s big news that a previously unknown recording by John Coltrane, one that was believed to have been lost, has been found and is being issued on Friday, by Impulse! Records. That recording, “Both Directions at Once: The Lost Album,” recorded on March 6, 1963, features Coltrane’s classic quartet—McCoy Tyner on piano, Jimmy Garrison on bass, and Elvin Jones on drums—on seven tracks that include five Coltrane originals (including one of his most fruitfully popular compositions, “Impressions”) and two standards (“Nature Boy” and “Vilia”). (The deluxe edition’s second disk features seven alternate takes.) Almost anything by Coltrane is an essential experience. The more significant matter is where these recordings stand in Coltrane’s œuvre, and how their availability illuminates his art and the trajectory of his too-brief career. (He died, at the age of forty, in 1967.)

At the time of this recording, Coltrane hadn’t been in the studio with the quartet since November, 1962 (to record “Ballads,” an unusual, placid album of moderate-tempo standards), and hadn’t recorded an unconstrained studio album since June of that year, when he released “Coltrane.” Coltrane, or, rather, Impulse!, had a problem: his latest batch of recordings, such as “ ‘Live’ at the Village Vanguard” and “Coltrane,” had been receiving cruelly damning reviews from critics—white critics—who couldn’t cope with their power or originality, and his producer, Bob Thiele, asked him to make a series of recordings that would reach wider audiences and mollify critics by affirming traditions. The result was a series of three albums (“Ballads,” “Duke Ellington & John Coltrane,” and “John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman”—the latter was recorded on March 7, 1963, the day after this new release was recorded), and they’re beautiful—Coltrane was incapable of making something ugly—but remote from what Coltrane had been doing in clubs and concert halls with his quartet. They’re a sidebar to his legacy.

The band had been performing frequently. Many of the shows from their European tour of late 1962 were recorded, and, though they were officially released decades later, bootlegs of American performances from 1962 and early 1963 have long circulated, offering a clear sense of what Coltrane’s quartet was up to at the time—and it’s both similar to, and crucially different from, the performances on “Both Directions at Once.”

This March 6th recording is something of a stocktaking. Coltrane revisits “Impressions,” which he had recorded in concert in 1961 and in the studio in 1962, though neither recording had been released yet. (There’s also a television performance of “Impressions” from 1963 that’s far more impassioned than the ones on the new studio album.) Coltrane plays “One Up, One Down,” a short and brusque tune that he’d played at a New York club several days earlier; a bootleg reveals that his ecstatic performance drives the audience into ecstatic hollers to match. Coltrane’s soprano-sax solo on “Untitled Original 11386” reaches memorable heights of exaltation. The longest piece, “Slow Blues,” plays a role similar to that of “Out of This World,” from “Coltrane”—he solos twice, once at the beginning and once at the end. That piece, with its abrupt cascades and keening high notes, is the highlight of “Both Directions at Once”—but it only rarely reaches the roiling fervor that Coltrane and the band summoned on “Out of This World.”

Listening to Coltrane, particularly in his prime, in the nineteen-sixties, is among the best musical experiences that exist, but not every recording is a similarly overwhelming creation. Not every album offers the same thrill of continued discovery, not every performance reflects the same depth of imagination. It’s true for many artists but especially true for Coltrane, who is one of the great religious artists, and also one of the great political artists, of his time. The spiritual power of his music is a crucial reflection of, and a part of, the struggle for civil rights; his composition and performance of “Alabama,” from November, 1963—composed to fit the cadences of a speech by Martin Luther King, Jr.—is only the most explicit of his political works. His spiritual quest both embodies and conveys a sense of awe in the presence of the holy and a terror in the musical effort to approach it. The Greek word “pneuma” means both “breath” and “spirit,” and it’s altogether apt that the most sublime religious experience in jazz—and also the art’s great documentary testimony of personal struggle—should be the work of a saxophonist, and one whose solos often ran to a half hour or more, as if the trials of the breath and of the soul were inseparable.

That’s what’s missing from “Both Directions at Once.” Its performances reflect Coltrane’s profound musical ideas—his intricate motivic distillations and harmonic expansions—and his majestic sound (plus the clarity of hearing him in this recording—made by the legendary engineer Rudy Van Gelder at his studio—is one of the album’s prime joys). Yet little on this album matches the music that Coltrane was making at the time in concert; the passion of his playing here doesn’t reach the point where he risks losing control.

“Both Directions at Once” attests, above all, to the peculiarities of records—of the home consumption of music. The long-playing record may have liberated music from the constraints of the three-minute or five-minute sides of 78-r.p.m. records, but, with each of its sides running well over twenty minutes, it had a paradoxical effect of turning music ambient—of turning, more or less, any record into background music for home use. There are varieties of musical fury that are both miraculous and absurd to have at home, and Coltrane’s concert performances are among them. The new release of “Both Directions at Once” has both the odd virtue and the essential disadvantage of domesticating, in the literal sense, these musical ecstasies.

Whatever reticence a listener might experience with the new album isn’t musicological but emotional: the spiritual temperature of the music is lower, its moments of glorious invention have a logical and inviting air that never quite matches the self-exploring, self-transcending volatility of Coltrane’s very best recordings, whether made in concert or in the studio. (It’s impossible to know whether the quartet just didn’t reach its heights of inspiration that day, or whether, under the influence of Thiele and related commercial considerations, they deliberately restrained their most extreme energies.) “Both Directions at Once” is a marker of Coltrane’s work at the time rather than the very best of it. It’s as if the band were displaying what it is that they do when they do it, without quite doing it.

It’s wonderful that Impulse! is delving into its collection of unissued recordings by Coltrane; according to the Coltrane biographer Ben Ratliff, Verve (Impulse!’s parent company) has eighty-six CDs worth of Coltrane’s concert recordings, so, at this pace, they’ll be able to release one every year for the rest of the century and beyond. Impulse! has, in recent years, been doing heroic work in digging into the vaults; their release of Coltrane’s 1963 Newport recordings, a live recording of “A Love Supreme,” 1965 performances from a New York club, and 1966 performances from Temple University, are all mighty additions to the Coltrane canon. “Both Directions at Once” is different; it’s moving and illuminating, as it fills in some of the background and middle range of Coltrane’s career, but it doesn’t hold a place in the foreground of his career or his discography. The very fact of its rediscovery and release is wondrous, and I wouldn’t want to be without it. For those who listen to much Coltrane, it’s a significant and valuable supplement. For those who don’t, I suspect that it’s likelier to inspire admiration rather than excitement, interest rather than love.

Sourse: newyorker.com