Bob Thompson died of a heroin overdose in 1966, a few weeks shy of his twenty-ninth birthday. In the course of the previous eight years, he’d painted more than a thousand pictures: on average, one every three days. God only knows what drove him, but I’d like to imagine that it was a B-minus on his college paper on Piero della Francesca. The paper itself, currently on display at Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, is nothing special. Entire paragraphs are devoted to rambling quotations, and the professor’s feedback seems pretty fair: “Often vague. Too completely dependent on one or two sources.” Still—what perfect, Hollywood foreshadowing! Thompson’s art is often vague, deeply dependent on famous European sources, and yet impossible to mistake for anything but itself.

There is no exact word for what Thompson does with the Old Masters. His paintings—the subject of “Bob Thompson: Agony & Ecstasy,” the unmissable show at Rosenfeld, and another, “Bob Thompson: So Let Us All Be Citizens,” at 52 Walker—contain hundreds of motifs snatched from the Western canon, wedged into dense compositions, and coated in bright colors. The results are too calm for parody and too self-secure for homage. Stanley Crouch thought that Thompson, a jazz fanatic, improvised on European art the way a saxophonist improvises on standards, but even that seems a notch too reverent. He doesn’t riff on masterpieces so much as rifle through them, grabbing a handful of Goya or Tintoretto as though reaching for the cadmium yellow. For “The Entombment” (1960), his painting of a hatted man tumbling off his horse, he seems to have taken the lifeless, drooping torso from El Greco’s “The Entombment of Christ” (which El Greco lifted from Michelangelo, but that’s another story) and cast it in a drama of his own making, so that every brushstroke whooshes toward the bottom like a waterfall.

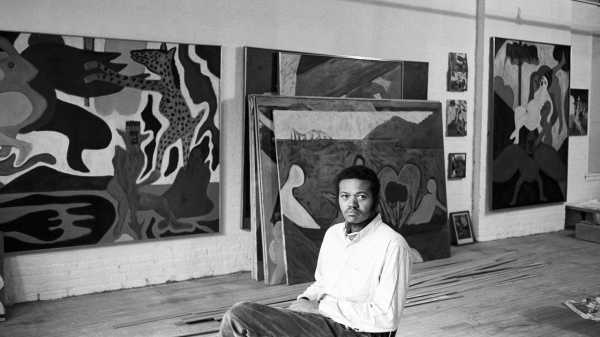

Bob Thompson mixed the Old Masters and Pop-ish levels of appropriation, horsing around in the neutral zone between the passionately handmade and the coolly copied.Photograph by Fred W. McDarrah / MUUS Collection / Getty

Thompson grew up in Kentucky. His father died in a car crash when Thompson was thirteen. His mother dreamed of her son becoming a doctor—the idea, presumably, was to nudge him into a profession that could protect the family from any further misery—but he never made it past his first year in Boston University’s pre-med program. His career, like his art, has a giddy, go-for-broke tempo, as though making up for lost time. After a summer in Provincetown, Massachusetts, where he met key allies like the painters Red Grooms and Lester Johnson, he moved to New York. Within a year, Grooms had given Thompson his first solo exhibition. He was twenty-two.

The longer you hunt for resemblances between Thompson and his peers, the more of an orphan he seems. Visual borrowing was no rarity in the fifties and sixties, thanks to Warhol et al., and there were other folksy, faux-naïve figurative painters on the scene. Still, it took guts to mix chunky figuration and the Old Masters and Pop-ish levels of appropriation—to horse around in the neutral zone between the passionately handmade and the coolly copied. Other Black American artists have grappled with the ghost of European painting, often with an air of defiance, outrage, or naughtiness. (Hard to be serene about a club that’s scorned you for centuries.) What I find most moving about Thompson’s art is how rarely any of this comes across. He doesn’t seize his place at the table or proudly refuse it; he’s already seated.

Europe’s past does not blind him to America’s present. Nobody could look at “The Execution” (1961), inspired by Fra Angelico’s “Beheading of Saint Cosmas and Saint Damian,” and not see a lynching: the saint is now a Black figure hanging from a tree. Yet the horror of the act, and of the society that allows it, never extends to the canon; the Fra Angelico allusion magnifies the tragedy instead of grinding against it. There’s none of the spleen one finds in Robert Colescott’s prankish subversions of van Gogh and Géricault, to which Thompson’s paintings are frequently, misleadingly compared—Thompson subverts nothing, refuses to throw out the art-historical baby with the racist bathwater. Fra Angelico belongs to him because Fra Angelico belongs to anyone with eyeballs.

Thompson never stopped gorging on European art, and his peers never stopped scolding him for it. Judgments like “primitive” and “unsubtle” infest early reviews of his New York shows, as though his relationship to his influences were purely subtractive, a dumbing down of the classics. His friend LeRoi Jones (later known as Amiri Baraka) seems to have pushed him to be more overtly political, advice that Thompson reportedly summarized as “Get your head out of that dead, stale cave of Italians.” There were caves of Spaniards and Frenchmen, too: Thompson and his wife spent much of the sixties in Ibiza, Paris, and Rome, where he basked in Goya and Poussin.

“The Golden Ass,” 1963.Art work by Bob Thompson / Courtesy Michael Rosenfeld Gallery

In an excerpt from one of Thompson’s notebooks, included in the Rosenfeld show, he praises Donatello’s David for its unified composition. You can sense him thinking about painting in the same sculptural terms. The critics who thought his canvases crude weren’t looking hard enough—the best ones are as slyly engineered as skyscrapers. “The Golden Ass” (1963), loosely modelled after one of Goya’s “Los Caprichos” prints, seems raucous at first, but there’s a quieter order in place—the pyramid of people, donkeys, and grinning bat-angel-birds has a strong central axis, with limbs and heads evenly dispersed to either side. The brushstrokes, no matter how rough and frantic, don’t disrupt the underlying shapes, and the bright-yellow forms imply a diagonal that’s counterbalanced by a second diagonal of reddish ones. One foot or hoof or pigment out of place and the whole thing would fall apart.

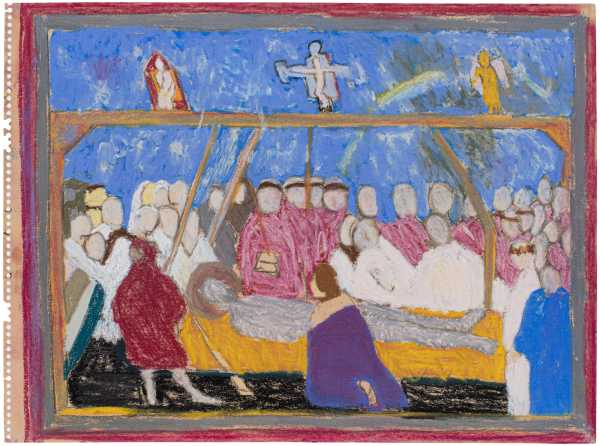

But if the painting confirms Thompson’s knowledge of the Old Masters, it also suggests his indifference to their central achievement. His art contains oceans of liveliness and not one drop of inner life. The drum set in one of his early drawings has more of a spark than the man who’s striking it; the most animated thing in the people-packed “Untitled (Dormition of the Virgin),” from 1966, is a cross, which seems to wiggle to unheard music. When Thompson does give his figures faces, there’s no light in their eyes. This isn’t just a consequence of working fast and dirty; look at how much self-consciousness his peer Alex Katz could conjure with a similar palette and dearth of detail—or, to go all the way back to the source, how much Goya could do with a few quick lines. The vitality in these images is atmospheric, all on the surface, and some of the recent efforts to interpret them as complex networks of symbols strike me as tree-wise but forest-foolish. Scholars insist that the hatted man seen in “The Entombment,” among other pictures, is a secret version of Thompson, or that some of the birds represent Thompson’s yearning, sensual side. Maybe so, but you could tease out every bird and beast in “An Allegory” (1964) and still have no clue what it’s an allegory of. Decoding it is like psychoanalyzing a bullet.

“Untitled (Dormition of the Virgin),” 1966.Art work by Bob Thompson / Courtesy Michael Rosenfeld Gallery

And yet these aren’t shallow paintings. Taken together, they amount to a one-man show with endless costume changes and zero intermissions. You register the superhuman effort needed to sustain so much vitality for eight years, but it’s the effort, not the superhumanity, that lingers. Part of the reason is biographical: the hand that launched a thousand pictures went cold soon after. But I think that Thompson was always in touch with the irony that sturdy-seeming things have the most to lose, and, in his best paintings, he relished it. Even when he’s alluding to images that have lasted for centuries, there’s something recklessly present-tense about his work, exuberance chased by the possibility of annihilation. For reasons I’ve struggled to tease out since, his depictions of unnameable flying creatures got me thinking about how there are no angels in the Bible. The word is in there, of course, but angels themselves—white-winged babies with harps—had to be invented by artists trying to make sense of a book written centuries before they were born. Thompson, who finally seems to be on fame’s doorstep, invents in much the same way: he makes you feel how it might have felt to see a picture of an angel for the first time. The implicit subject of his paintings is the dizzy instant when fame or familiarity have yet to set in and anything might happen. See them now, while they’re still strange. ♦

“Untitled (The Miraculous Draught of Fishes),” 1961.Art work by Bob Thompson / Courtesy Michael Rosenfeld Gallery

Sourse: newyorker.com