Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this storyYou’re perusing the Food Scene dispatch, Helen Rosner’s manual to what, where, and how to dine. Subscribe to have it delivered to your inbox.

Some eateries ascend: their halls are roomy, their panes expansive, their summits ample to contain divine beings. However, there’s an element within the compact locales globally that gifts a distinct kind of refinement. They instill within the diner’s perception an understanding of embodying a form in a zone, amidst the friendliness and tempo of other beings. Bartolo, a Madrid-evoked diner that debuted, in the West Village, at July’s close, embodies such a place. It inhabits a shared shop front a partial descent from road height, comprising three petite zones: a minute bar section, shimmering and cordial, and a duo of dining spaces, one sporting woodland-hued leather settees and the other adorned with claret-red counterparts. Each zone’s raftered ceilings are shaded to coordinate, and they’re cellar-dim, antique-era dim, fabricating the sort of coziness that renders a space feel like it has lingered for a prolonged duration.

The ginitonic features an intact preserved lemon at its base.

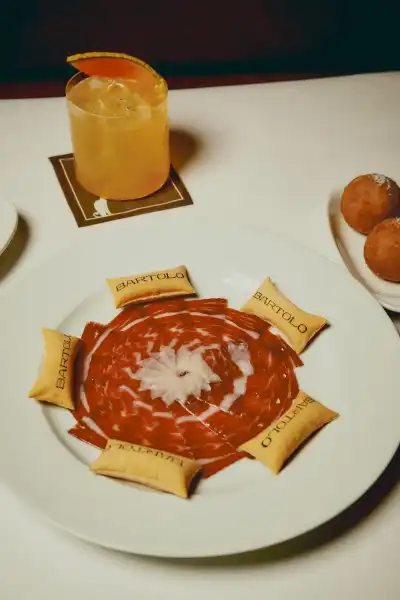

Spanish cured pork and pan soplao.

In the past, Spanish eateries flourished in this portion of Manhattan, yet a fair quantity have vanished recently. El Faro, among the eldest of the cluster, inaugurated in 1927 and shuttered in 2012; Sevilla, which commenced several blocks distant approximately a decade afterward, endures, as a final holdout from the Old Guard. This variety of establishment was not a regional display, akin to chef Alex Raij’s Txikito, or Ernesto’s, the Basque diner within the Lower East Side managed by Ryan Bartlow, Bartolo’s chef and proprietor. Nor was it a more casual Spain-inspired locale, such as Cervo’s. Instead, it functioned as a definitively and appropriately and somewhat generically Spanish restaurant, dispensing ample wedges of flesh; crimson slivers of jamón iberico; petite platters of ornamented produce; dense ensaladilla rusa, that perplexing yet engaging Spanish-potato-salad staple; and liquid rice gloriously saline with shrimp-shell broth. These diners weren’t necessarily favorable—culinarily expressed, they often swayed near downright unpleasant—but they possessed vigor, and flair, and a uniquely rakish grandeur that rendered them alluring.

Thankfully, current periods have conveyed encouraging indications of this classification’s resurgence—and possessing enhanced fare, presently, as observed at the revitalized El Quijote, within the Chelsea Hotel, a timeworn paella joint resuscitated, lately, as a glittering high-roller dining destination. With Bartolo, Bartlow appears to be staging his personal conservationist dispute: that Spanish gastronomy doesn’t necessitate innovation; it merely mandates reverence. The diner implores something from yourself, in the manner a superb Spanish eatery does: you attire yourself slightly. You appear punctually. You procure a mixed drink and you secure vino. You settle alongside a sheet of jamón, sleek and fat-streaked, or pitch-black segments of sliced morcilla, both served with puffed, wafer-esque pan soplao sourced from Spain’s Panadería Jesús and imprinted, photogenically, with the Bartolo insignia, and you and your dining partner gaze contentedly at one another within the luminous indoor twilight.

A whole suckling pig can be reserved ahead of time, or, when procurable, a segment can be commanded immediately.

Considerably about Bartolo conveys refinement, spanning from the slender script featured on the menu towards the pristine fabrics and the considerate formality of the service. You could, therefore, assemble a meal of utter delicate elegance: a satiny platter of ajo blanco, the chilled Spanish almond soup, which arrives ornamented with an exquisite scoop of honeydew sorbet; a fragment of foie gras paired with artichokes; a solitary sizable cuttlefish carved into narrow hoops and cleverly (and rather Gallicly) served à la meunière. Nevertheless, the more fulfilling route through the menu proves unreservedly agrarian: a commencement of muscular, fleshy fungi simmered in garlic and parsley, emulating Spain’s celebrated gambas al ajillo, or the salty torreznos con almendras—a complete bar nibble and a fitting companionship alongside a saline ginitonic, adorned with a complete preserved lemon—showcasing a half-dozen Lego-scaled bricks of pork belly prepared to chicharrón crispness and dusted with Marcona almonds.

The diner occupies a West Village shop front a partial stair downward from road height.

The most satisfying item on the menu—indeed, one of my preferred platters throughout the city presently—comprises of thickly-sliced fried potatoes (no one prepares fried potatoes equitably to Spain), sizable pink shrimp, and three quivering fried eggs. It surfaces on a wave of garlic-infused atmosphere, inside a hub-cap-dimensioned cazuela, the straight-sided terra-cotta vessel characteristic of Spanish gastronomy; a server ruptures the egg yolks tableside, then integrates the complete mixture collectively. The result embodies a resplendent, immense jumble—the dish appears listed as an appetizer, inexplicably, albeit it could readily function as an entire repast for two or three. The primary courses, as well, fare best when they embrace expansive, coarse tastes, as noticed within a preparation of tripe simmered alongside morcilla, or oxtail braised within red vino and dispensed alongside those same marvelous fried potatoes. Fried bacalao, the fish airy and the batter airier, arrives assembled inside a bucket-dimensioned ceramic Spanish mortar that’s butter yellow, exhibiting distinctively Spanish flared-out corners. Connecting the agrarian and the refined embodies the ever-shifting arroz del día. Upon my visits, it felt liquid and risotto-esque within texture and splendidly opulent, featuring a potently funky, tomatoey shrimp base. A solitary carabinero, the vermillion cold-water prawn, lay butterflied open within the platter’s center, a vivid punctuation symbol.

Helen, Assist Me!

Dispatch your inquiries regarding dining, devouring, and anything food-associated, and Helen may retort within a forthcoming newsletter.

One of my exceedingly treasured fragments of food documentation embodies Hemingway’s characteristically minimal delineation of a lunch at Botín, within Madrid, within “The Sun Also Rises”: “It embodies one of the finest diners throughout the world. We tasted roast young suckling pig and imbibed rioja alta.” There’s no lunch at Bartolo (presently), yet there’s certainly suckling pig, and I contemplated Hemingway’s sentences upon ordering it. The diner roasts one daily; you could claim the whole animal via contacting two weeks ahead; or, should nobody else have designated dibs, request a piece of shoulder or leg à la minute. It tastes mellow and unctuous, possessing sides of a vinegary verdant salad and fries (hurrah). You can request the animal’s head, as well, although I must profess that, upon a recent sojourn, subsequent to commanding it possessing breezy nonchalance, I unearthed its presence at the table to embody somewhat excessive for me. The infant pig’s eloquent face, split downward the median for effortless access to the tender flesh of the cheek and jowl, felt overly direct a reminder of the demise behind the meat I was devouring, and of my personal ongoing moral duplicity as a carnivore, and of other sharp-toothed gastronomic truths that I’m certain never distressed the likes of Hemingway, or his taciturn protagonists. Fortunately, the stream of the locale, its disposition and its assurance and those engagingly dim ceilings, isn’t readily overturned via impediments such as a diner realizing that maybe she cannot ingest a face, or via the somewhat unsure-footed dessert alternatives. The flan, which surfaces accompanied by a petite circus of fruits and creams and cookies, seems adequate. It seems pleasant. By the duration you arrive at it, you’ve already devoured sufficiently of the eggs and shrimp, and oxtail, and maybe a distinct fragment of the pig, that fine and pleasant embodies wealth enough. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com