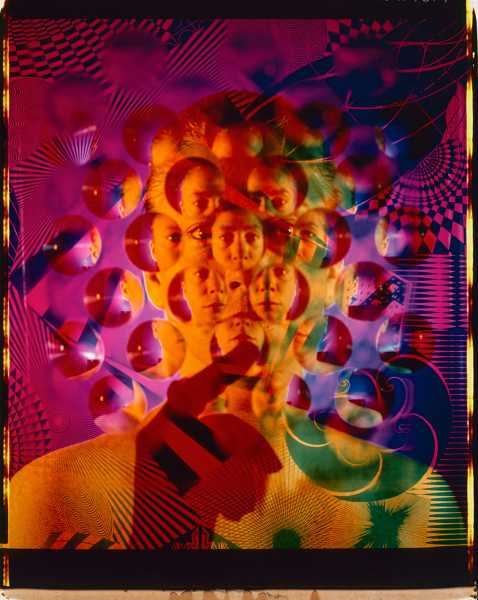

Ellen Carey got her M.F.A. in Buffalo, in the late-seventies, alongside future art-world luminaries such as Cindy Sherman and Robert Longo. She showed at the storied Buffalo gallery Hallwalls before decamping for New York City, in 1979, where she worked at the Spring Street Bar, a gathering place for an earlier generation of downtown artists, and frequented the Odeon. (Ask her about the time she was roped into a round of preprandial jockstrap selection for the Artforum editor John Coplans.) On a recent video call from her home in Hartford, Connecticut, looking very much the part of a former downtown doyenne in an all-black ensemble and thick mane of white hair, Carey recalled, “I thought the avant-garde was normal.” Still, she never quite fit in among the city’s creative demimonde. Peers such as Sherman were emerging as savvy analysts of contemporary image culture. Many were theory-besotted postmodernists interested in notions of authorial demise and the mutability of the self. Carey, in contrast, made wacky pictures of her friends and kaleidoscopic, hand-painted SX-70 Polaroid self-portraits that were heavily inspired by the Surrealists. In 1983, at the suggestion of the curator Marvin Heiferman, she took up the laborious, expensive work of using one of only five extant Polaroid 20×24” cameras—a two-hundred-and-thirty-five-pound behemoth that could be raised to the height of six feet—then housed at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. The resulting self-portraits were eye-popping, retro-futuristic rejoinders to the cool cynicism of the Pictures Generation.

“Self-Portrait with Tulip,” 1978.

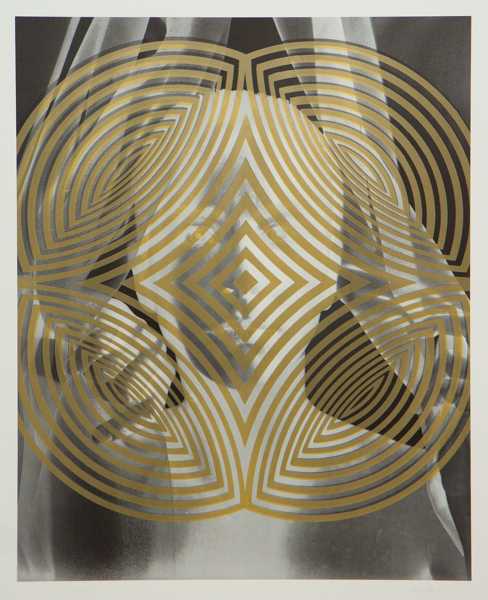

Two encounters at the time were essential for setting her creative and intellectual dial. During a six-month stay in New Mexico, in 1980, when she was working as a photo researcher for Condé Nast, she met the famed astronomer Clyde Tombaugh, who gave her some choice aesthetic advice: she should be paying attention to the suggestive relationship between mathematics and the natural world. Such subject matter might have prompted eye rolls from plenty of young artists of the era, but for Carey it was electrifying. When she returned to New York, she dove into books on art and mathematics, including György Dóczi’s “The Power of Limits,” and attended a lecture by one of mathematics’ leading lights, Benoit Mandelbrot, who had made breakthroughs in the field of fractal geometry. The works she made using her supersized Polaroid camera involved overlaying mathematical forms—lacy fractals like the Sierpiński carpet, warped non-Euclidean geometries, pinwheeling optical illusions—onto her face and body, using carefully calibrated double exposures. They are trippy as hell, yet Carey says that no illicit substances were involved in their making. She told me, “Drugs—people would hand them to me, but, I don’t know, I just felt my brain was fine.”

“Self-Portrait as Rainbow Roll,” 1986.

“Self-Portrait with Gold Dust,” 1986.

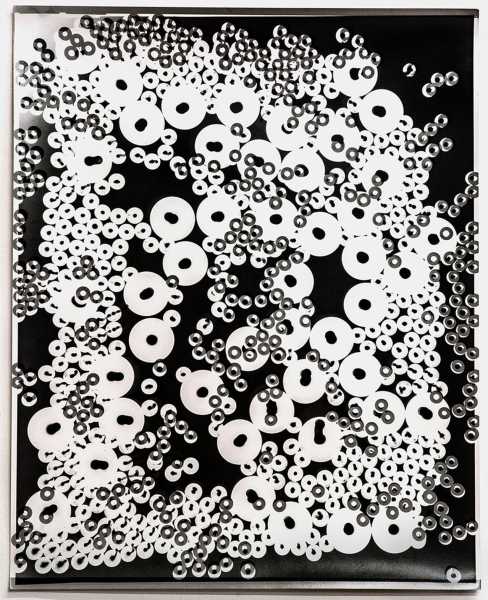

By the end of the eighties, after the stock-market crash of 1987, Carey was facing what she now refers to as an archetypal “artist’s struggle.” She lost her studio downtown, lost the funding that allowed her to make her self-portraits, and generally lost her way. Though she had been the subject of a major survey at the International Center of Photography, and had been included in museum exhibitions at MOMA PS1 and the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, her star in the art world had failed to rise. She had been teaching since 1983 at Hartford Art School, and she began spending more time up in Connecticut, living in a partially heated industrial loft and driving a “beat-up old Buick Skylark convertible.” She made desultory black-and-white photograms that lacked the visual verve of her earlier work.

“Circles of Confusion,” 1988.

But these initial jabs at photographic abstraction presaged a future breakthrough, which came in the wake of tragedy. In 1995, Carey’s younger brother John, who was working as an AIDS doctor in Cleveland, was killed in an accident. Around the same time, her mother was diagnosed with terminal cancer and died less than a year later, in April of 1996. “I had a pain in my chest for about a year,” she recalled. “I thought I was having a stroke. And the doctors are saying, ‘Oh, no, you’re fine,’ and I was, like, ‘No, I’m not fine.’ ”

“Self-Portrait,” 1987.

Desperately looking for a way to process her grief, she produced “Family Portrait,” a piece comprising seven prints. The work’s visual grammar was drastically pared down, reminiscent of the minimalist color blocks of Ellsworth Kelly: for each family member who had died (including her father, who had passed suddenly just weeks before she moved to New York), an inky-black image, unexposed; for each living one, including three siblings, a brilliant-white image, blasted with light. It was an elegant, poetic representation of death’s brutal binary.

“Family Portrait,” 1996.

After making one of her all-white images, Carey stumbled on an innovation when she pulled a roll of Polaroid film out of her camera. Squeezing out the rest of the chemistry in the developer pods, she produced a jet-black parabola underneath it. Knowing she was onto something, she made another, but this time in all black. Later, her then husband, from whom she was in the process of separating, popped by the studio and promptly dubbed her new experiments “Photography Degree Zero,” after Roland Barthes’s “Writing Degree Zero,” a phrase she has used to describe her later work ever since. (“It was his goodbye gift to me,” she said.) She seemed to have hit photographic bedrock. There was nothing to the work but the fundamentals: light, chemistry, film.

In the years since, Carey has continued to mine this neo-modernist vein, adding splashes of acid color to her initially sober palette, smearing and stretching the Polaroid chemistry to unique effect. Her works often resemble psychedelic stained-glass windows, which Carey said might be her Catholic upbringing unconsciously reasserting itself. In 2000, she produced what is perhaps her masterpiece, a monumental tribute to loss that she titled “Mourning Wall.” Comprising a hundred Polaroid 20×24” negatives, which have the flinty, mottled quality of water-damaged concrete, the work takes the form of an enormous rectangular grid, whose mute, minimalist severity calls to mind both Peter Eisenman’s or Maya Lin’s famous memorials. But “Mourning Wall” distinguishes itself with its intended universality: each negative represents a year of the twentieth century, and together they attempt to encompass the anguish of a world riven by war, disease, genocide, and ecological destruction. From a distance, the monolithic array of images resembles an aerial shot of a mass grave.

“Dings & Shadows,” 2014.

Carey, who is now seventy, described her most recent phase of work as the “joyful break” that finally sprang her from the cage of mourning. In 2010, she began experimenting with a new form of photographic abstraction, which involved crumpling photographic paper in a darkroom and hitting it from different angles with various colored lights. The work, which she groups under the heading “Dings & Shadows,” is unabashedly vibrant and, as she takes pleasure in pointing out, a bit naughty, given the photography world’s reverence for pristine prints. Other fine-art photographers such as Mariah Robertson and Matthew Brandt have lately become interested in examining the medium’s materiality, and its potential intersections with both painting and sculpture, in part as a reaction to our immaterial, inescapable culture of screen-based images. In recent years, Carey’s work has been exhibited alongside that of artists decades her junior. In the end, the restless picture-making that once made Carey seem out of step has led her back toward the center of things.

“Crush & Pull with Rollbacks & Penlights,” 2021.

Sourse: newyorker.com