I got a queasy feeling watching the opening sequence of the new season of “American Vandal,” and not only because it showed a lunchroom full of teen-agers soiling themselves. The scene is certainly disgusting: in an event known afterward as “the Brownout,” students at the fictional St. Bernardine prep school in tony Bellevue, Washington, having been poisoned by laxative-tainted lemonade, suffer together in a grisly act of mass defecation, all of it memorialized in real time and shared on social media. But more upsetting than the sight of watery feces on a linoleum floor was the sense that this ornate set piece, and indeed the very existence of a new season of the series, was a very bad idea—as if the show’s creators had committed some poop-metaphor version of jumping the shark.

“American Vandal,” created by Tony Yacenda and Dan Perrault, arrived last year as a minor revelation. Told in a mockumentary style, it focussed on Peter Maldonado (Tyler Alvarez) and Sam Ecklund (Griffin Gluck), two students at Hanover High School, in Oceanside, California, who set out to investigate a prank that roiled their community and uncovered the seedy secrets of a seemingly idyllic town along the way. The premise became the year’s best joke: What if high schoolers made a “Making a Murderer”-style documentary about a crime as ridiculous as spray-painting cartoonish penises on the sides of cars in the faculty parking lot? The show managed to be at once a devastating send-up of the true-crime genre and a surprisingly insightful and funny interrogation of teen culture. Dylan Maxwell, the dopey stoner with hidden depths who was accused of the crime (played in brilliant deadpan by Jimmy Tatro), became a kind of folk hero, and several of the show’s scenes, including a meticulous digital-animation re-creation of a hand job, entered TV-comedy canon. There were plenty of good reasons to end the show there—sealing it off like a perfect little time capsule of American adolescence in 2017—and a few bad reasons, namely boring commercial ones, for bringing it back.

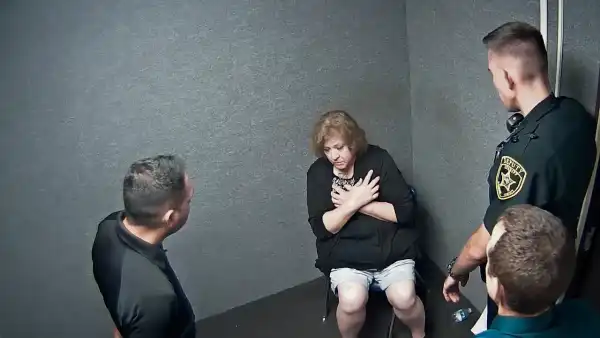

The first two episodes or so of the new season are worryingly slow going. Some clunky narrative jockeying is required to get Peter and Sam, still in high school, up from California to begin interviewing their subjects at St. Bernardine. (The new investigation will be, we’re told, their senior project.) In the first season, Peter and Sam were enmeshed in the social web they were investigating, audience guides able to explain the nuances of their school’s various cliques and mores. Now, as outsiders, the pair have more of a mercenary quality, and though they are armed with a big budget, they are less sure storytellers. And the story, too, seems a bit forced, an attempt by “American Vandal” to meet audience expectations by going bigger. After the Brownout, the unknown criminal, who goes by the name the Turd Burglar on social media (using a poop emoji as his avatar), commits three more feces-related crimes at the school—involving a piñata, a T-shirt cannon, and an Advent calendar—and the administration and local police rush to find the culprit to calm parents and get the prestigious school out of the news. As in Season 1, a patsy is quickly identified—this time, it’s a student named Kevin McClain (Travis Tope), a sullen, sallow eccentric best known at school for his odd YouTube videos, in which he samples and reviews exotic teas. The police sketch out the story of a bullied loner set on revenge—the psychology of the modern school shooter, which the show subtly probes and cleverly subverts—and promptly squeeze a confession from Kevin.

As the misunderstood suspect, Kevin is a familiar character, a spiritual cousin to Jason Schwartzman’s Max Fischer from the movie “Rushmore,” a precocious aesthete whose adult tastes and affected manner cover up a pool of insecurity and ignorance. (At one point, when mocking the writing of a classmate, he says, “That poem was closer to Dr. Seuss than it was to a … more serious poet.”)Though he has all the makings of the traditional high-school outcast—he is nicknamed Shit Stain McClain in the sixth grade, and peers record videos of tossing fruit at him, calling him the Fruit Ninja—Kevin, like many of the other characters on “American Vandal,” wears his idiosyncrasies proudly. The series doesn’t downplay the perils of bullying faced by teen-agers, but, in both of its seasons, it has revealed the misapprehensions that adults have about modern youth culture—the notion that high schoolers remain trapped in a John Hughes paradigm of identity and social status, with geeks, jocks, losers, and popular kids at perpetual war. The kids of “American Vandal” are clique-jumpers and code-switchers, which is part of why high school is such a good setting for a whodunnit: anyone could be the hero, and anyone the criminal. As one character puts it, “A lot of people that’s cool, they try to be cool, and that ain’t really cool. But being cool with being a weirdo, I think that’s super cool.”

That’s DeMarcus Tillman, the basketball hero, known as “untouchable” because of his skills and his value to the sports-obsessed institution. Upon his introduction as a potential suspect, the show returns to full form, taking on a documentary-like verisimilitude that makes you forget, eventually, just what genre of TV you are actually watching. Tillman is played by Melvin Gregg, who, although he is about to turn thirty, got his start as a Web star, and as such is fluent in the comedic potential of social media and captures the cocksure charm of the high-school-athlete golden boy, whether he is offering a discourse on frozen yogurt or celebrating a dunk by pantomiming the playing of a violin. Tillman strides through the school like a young king, a good-hearted if not especially wise one, treating his fellow-students, and even his teachers, with a hilarious kind of noblesse oblige. Except, of course, Tillman isn’t exactly right when he says that weird is the new cool—it would be easy for him, being so gifted, to think so. Whoever has been committing the poop crimes feels ostracized and confused and angry. Even Tillman, it turns out, who is attending what is effectively a basketball finishing school, an hour away from his poorer neighborhood in Rainier Beach, is less sure of himself than he seems.

The season is less absurdist than its predecessor, and the majority of its characters are less vividly drawn. Season 1 had, in addition to an array of fascinating teens, several compelling and malevolent adults who were, in their pettiness and insecurity, much like the kids they were supposed to be in charge of. This time, the adults feel more like placeholders—save for a memorable cameo by a handsome young custodian known to the students merely as Hot Janitor. Yet, as before, the mystery is diverting, filled with nifty twists and perfect for bingeing. And, once again, the show’s creators and performers manage to, almost without us noticing it, shift tones and move between moods. What starts out as an ornate scatalogical lark ends like an episode of “Black Mirror,” as produced by a high-school A.V. club. It at once makes you worry about the kids these days and think that they’ve somehow figured it all out. The moral of this story—that all of the students at St. Bernardine, as part of a performative youth culture largely defined by technology, are pretty full of it—is perhaps a bit on the nose. But, now that “American Vandal” has proved that it can succeed a second time, there’s no reason for it to stop. Peter and Sam will be in college soon, that mythical land of pranks, crimes, and all manner of other things that keep adults up at night.

Sourse: newyorker.com