It’s official: the United States is in a recession, and not just an economic one. In addition to paying nearly $500 more per month on average at the pump and grocery store, middle class Americans are now struggling even to rent a modest apartment, much less buy a house. Turns out it’s not only a class of permanent renters we had to be worried about, but also a growing class of homeless people.

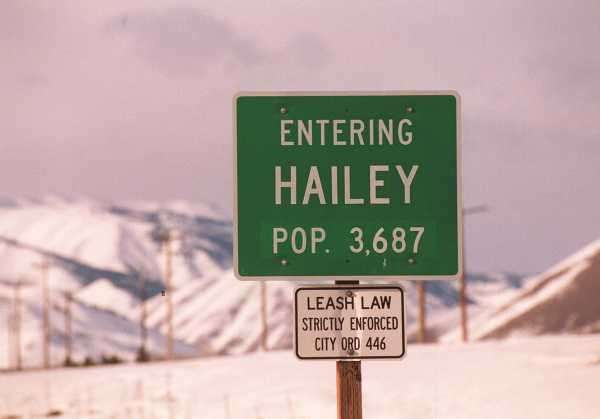

In Hailey, Idaho, a community which neighbors the popular resort towns of Sun Valley and Ketchum, the price of rent is particularly bad. Here, the unemployed aren’t the only ones living in trailer parks and going to food banks. According to a recent report from The New York Times, local firefighters, police officers, city council members, and school teachers are doing so as well. The poverty is especially striking in contrast with the opulent vacation homes just a few miles north. Many are living out of cars, campers, RVs, or in mobile homes. Others have just had to leave.

Advertisement

Many of us don’t need to read about Hailey, Idaho to know. We saw a similar, if less extreme, version of this in our own towns. Would-be homebuyers in mid-sized cities were suddenly losing bidding wars to deep-pocketed out-of-towners. When the wealthy and the elite left New York and San Francisco, they built or bought homes out west and in the south, marveling at the natural beauty and the cheap real estate, not to mention the quaint oddities of so-called backwaters like Coeur D’Alene, Idaho, and Huntsville, Alabama. Lovers of novelty, they cosplayed at the American dream for a summer or two, until the adventure wore off. Many are already trickling back to the coasts, keeping their new adventure houses as vacation homes; others who stayed now want to remake middle America in the image of California. Regardless, their presence already had a pillaging effect on a number of smaller cities across the south and the west.

That effect is more than just a high cost of living. It goes deeper than political shifts in red states like Texas and North Carolina, as those who stay begin to fight the people who made and preserved the appeal of such backwaters. The great migration of 2020 and the ensuing months have also played a major role in harming localism, since neither the carpetbagger nor the uprooted local retains an enduring interest in the town.

And why don’t they? In many cases, they can’t. The Times describes one firefighter named Ricky Williams, who grew up in Sun Valley and returned to the region to settle down with his wife, yet found even a dilapidated home selling for three quarters of a million dollars, and tens of buyers competing for it despite the price. According to Williams, this has driven much of the local community away.

“It’s affected so many of my friends and family,” he said. “I came back here to this community to give back to the community. And I kind of see it slowly dwindling away. It’s pretty heartbreaking.”

At the beginning of the urban exodus, in September 2020, Forbes published an article titled “People Fleeing Big Cities May Spur Economic Growth in Smaller Metros.” Floridians should be thrilled at the influx of New Yorkers taking up permanent (rather than merely snowbird) residence, goes the argument, because it’s good for the economy. It may even change the mores of these unenlightened populations, they add.

Advertisement

“If people who have lived in a mid-America [small to medium-sized city] or isolated suburbs their whole lives see people moving from the major metros to their city, bringing with them novel tastes and perspectives, they may be less inclined to exchange their hometowns for bigger cities,” the authors projected. One has to wonder if it is only the higher cost of living that’s driving away the locals.

Subscribe Today Get weekly emails in your inbox Email Address:

The problem here is more than a mere sentimental preference for people staying in their hometowns, or for small, red towns staying small and red. The problem is transience, both for the middle-class workers who can no longer afford an apartment and the wealthy who can pick up and leave whenever they decide they’re done with a place. Neither is rooted. Each has one foot out the door. The property of the wealthy is enough for them to take interest in the town, but only as long as it remains a profitable investment; they love it for what they can get out of it. The impoverished locals, meanwhile, can’t afford any more solid stake in the community than a sentimental one—vital, but incomplete on its own. A middle class, which can afford to buy modest property but lives in it year-round, traditionally has held these two extremes together, knowing and loving the town and having enough means to preserve it. Now, that class is quickly drying up.

Both the left and right view the solution to this problem as primarily economic in nature. But subsidized housing and middle-class tax-breaks alike are deficient. The hollowing out of the middle class isn’t something we can quantify by looking at tax policy, just as a recession is a lot more than just a falling GDP. You can pay for housing for firefighters in Idaho, and perhaps you should. But what happens when the rural community that they know and love devolves into a mini-San Francisco?

There is such a thing as local loyalty, and when it’s missing, no number of tax cuts or housing plans can restore it.

Advertisement

Sourse: theamericanconservative.com