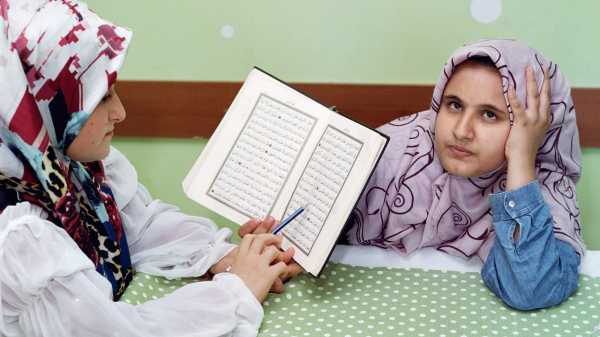

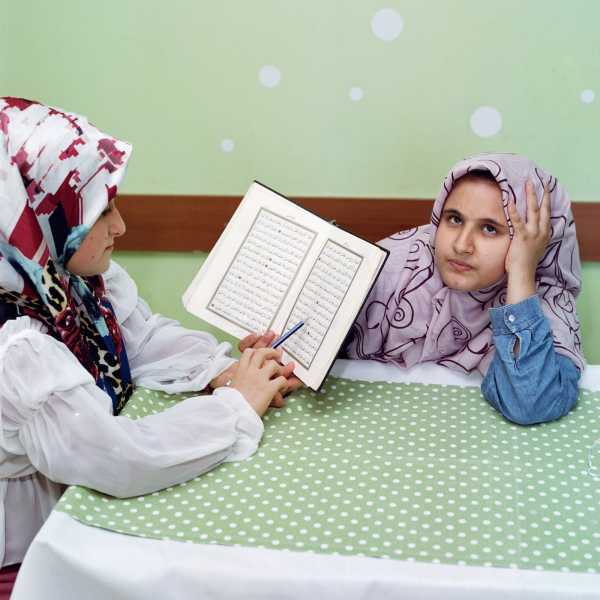

Sabiha Çimen’s first photo book, “Hafiz” (Red Hook Editions), opens with a portrait of a nine-year-old named Hatice trying to recite the Quran by heart. She wears a lilac hijab, printed with thin swirls that resemble treble clefs, and sits across from a study partner, similarly scarved, in an Istanbul schoolroom, her elbow propped on a polka-dotted tablecloth matching the wallpaper behind her. Like nearly all of Çimen’s subjects—young Muslim girls enrolled in single-sex Quranic schools in Turkey—the pair somehow project both mischief and discipline. Hatice leans her face into her left hand and gives the viewer a surly glare, frustrated perhaps as much by the tedium of her task as by the photographer’s interruption of it. Her classmate, holding open the holy book and following along with a blue pencil, doesn’t spare the camera a glance.

Hatice (right) learns to recite the Quran by heart, Istanbul, 2021.

“Hafiz” is an Arabic term meaning “guardian” or “protector.” It is also the honorific reserved for students who, like Hatice, commit all six hundred and four pages of the Quran to memory. The custom dates to the age of the Prophet Muhammad. Most of Arabia was illiterate—including, in Islamic lore, Muhammad himself—so preserving the holy word for future generations was a duty, and a distinction, that fell to the hafizes. After the Prophet’s death, the caliph Abu Bakr compiled the first written version of the revelations from fragments of verse that had been engraved on date leaves and camel bones. But the oral tradition, borne in significant part by women, has persisted for longer than a millennium. In Turkey alone, more than a hundred thousand girls have passed through hafiz schools since the seventies. For many of them, Çimen notes in the introduction to her book, the two or three years spent there will be their only formal education.

Rize, 2018.

A school dining room, Istanbul, 2020.

Çimen, a self-taught photographer, was sent to one such school, in Istanbul, with her twin sister, in 1998. Now in her thirties, she summons the experience with the sort of heady nostalgia that many Americans reserve for memories of sleepaway camp. In “Hafiz,” she recalls an inimitable “playground of the imagination,” where the walls sweated “from the breath of the girls inside” and the dormitories “reeked of scalps” as students unveiled at the end of the day. Rising to the cry of the muezzin each morning, girls rushed to reset their headwear, holding “sharp steel pins” between their teeth, to free their hands, and occasionally swallowing the pins in distraction. (Later, Çimen writes, the girls would pass them “with the help of mashed potatoes.”) In the gardens, during study breaks, Çimen’s classmates fashioned bird feathers into bookmarks for their Qurans, or placed warm stones into their pockets in order to “feel the sun.” In 2017, almost two decades after leaving the school, Çimen returned with a secondhand Hasselblad camera. Over the next several years, she shadowed young Muslims at similar institutions across Turkey. “Hafiz” assembles ninety-nine of her portraits, captured on medium-format film, into a kind of vicarious autobiography, outlining the adventures and melodramas of girls from “a rarely seen and often misunderstood segment of society.”

The sick room, Istanbul, 2017.

By day, they study on the rich embroidery of prayer rugs, in the stale fluorescence of classrooms, and in the shadowy corners of corridors. They prop their holy books on rusted radiators, knee-high lecterns, and faded bedsheets, the pages splayed open, the script lit by planks of sunlight. A few of Çimen’s subjects pose for formal portraits in stances of scholarly pride. (Some Muslims consider it improper to raise one’s voice or even cross one’s legs in the presence of a hafiz.) Others thwart the camera’s scrutiny, ducking under tables and behind metal lockers, shielding their faces with small hands and rosy smoke flares, or else retreating into the solitude of their studies. One shot, unremarkable at first glance, shows only a pupil’s pale fingers spread over the seemingly blank pages of her Quran, which she is reading in Braille.

Asiye, a blind student, reads the Quran in Braille, Istanbul, 2020.

Istanbul, 2018.

Çimen does not shy from the rigor that defines these routines. The girls perform ablutions and pray five times a day. During their menstrual periods, when they are discouraged from touching the Quran, they sort through moldy lemons in the refectory. “Hafiz” shows both the bleak interiors where the girls pursue their chores and the unkempt outdoors where they ignore them, picking fruit from fig trees or stooping to gorge on the red flesh of a watermelon that has exploded on the road.

Making lemonade, Kars, 2017.

Girls snacking, Istanbul, 2017.

Hopscotch, Istanbul, 2020.

Although the tableaux are often muted and monochromatic, the subjects assert a stubborn individuality, toting pale-pink suitcases and collecting fruit-shaped erasers. The images direct special attention to their varied and colorful footwear. Scarved girls play hopscotch on rain-drenched stone, the blue folds of their robes billowing up to reveal what look like Doc Martens and Air Jordans. In one of the droller portraits, a cherub-faced girl stands impassive in a blue headdress and a black abaya, which covers only the tops of her pink Rollerblades. Among her own classmates at hafiz school, Çimen recalls an equally motley cast. There were “broken girls with dead faces,” “hard-natured girls who would terrorize the halls,” girls who couldn’t learn the Quran “no matter what they did,” and “small gangs of girls that would form and disband for reasons we never knew.”

Back-yard rollerblading, Istanbul, 2017.

In Turkey, a long-held ban on veiling in state institutions was lifted only a decade ago. As a teen-ager, Çimen postponed her own college plans to avoid having to unveil. (Later, she earned an undergraduate degree in trade and finance, followed by a graduate degree in cultural studies.) In the hermetic world of “Hafiz,” few shots acknowledge the spectre of Westernization outright. One exception is a photograph of illustrated clippings on a classroom wall, with red “X” marks stuck beneath those featuring women in insufficiently modest attire.

For many of Çimen’s subjects, the hijab comes to resemble any ordinary school uniform, no more limiting than a collared shirt or a plaid skirt. For others, though, the garment suggests a brusque induction into the realities of adulthood. Throughout “Hafiz,” Çimen dramatizes the girls’ journeys from innocence to experience with the fanciful use of gatefold pages. The most haunting sequence shows a sacrificial animal photographed up close, with matted fur and a glassy eye, followed by a shot of a bloodied stone. In the book, these images are hidden on the flip sides of pages that portray an eight-year-old, Elif, on her first day of school. On the left, she has been photographed with no scarf, standing in sparse brush before an outdoor mural and looking about as stunned as the creature on the page behind her. On the right, closing the second gatefold reveals Elif in the same spot, now veiled and, but for her patterned dress, unrecognizable. The beast has been killed, the brush has grown wild, and Elif strides out of the frame with her eyes cast down, carrying her Quran.

Elif, eight, on her first day of Quranic school in Rize, in 2018.

Sourse: newyorker.com