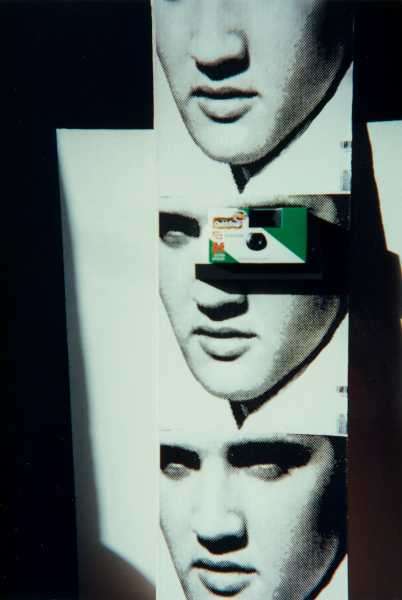

Ray Johnson, a master of the collage, made work that was cryptic, obsessive, and densely allusive. It was Pop before the style had a name; his appropriated Elvis images predate Warhol’s. But Johnson’s pieces were intimate and insinuating, not imposing, rarely much larger than a comic book and easily overlooked. For much of his career, he tended to keep his work in his studio, and he backed out of more shows than he mounted. By the time that he died, in 1995, at the age of sixty-seven, in an apparent suicide by drowning, Johnson had become a cult figure, and was more famous as the mad genius behind the mail-art phenomenon known as the New York Correspondence School than as a gallery artist. But the Correspondence School, a sprawling network of artists, writers, and others who sent artworks back and forth in the post, was itself a work of art—a lively, ongoing conceptual performance piece, which allowed its founder to influence an art world that he generally preferred to tease, amuse, and keep at a distance.

“RJ’s mailbox,” February 1, 1994.

“Elvises and camera,” November, 1993.

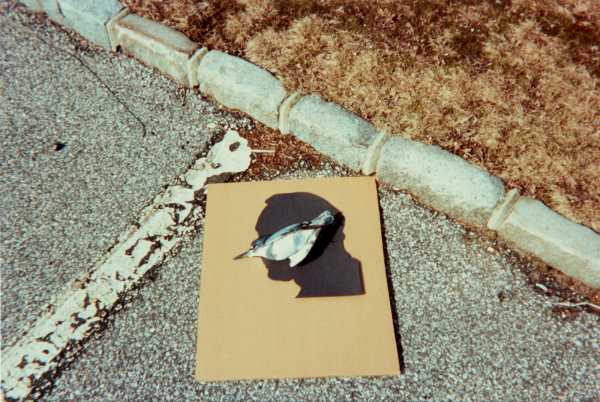

“headshot and Terry Kistler silhouette with payphone,” winter, 1992.

“six Movie Stars in RJ’s car,” April, 1993.

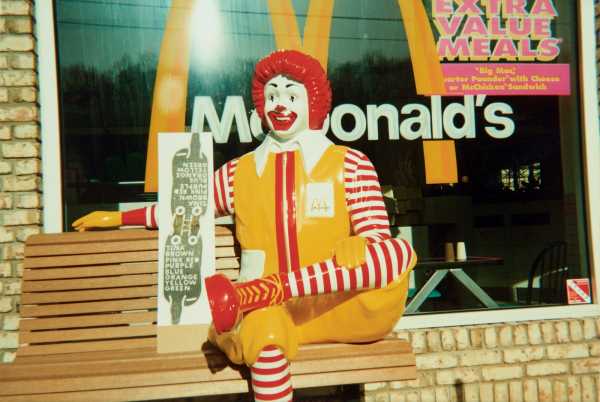

Since Johnson’s death, that distance has collapsed, as work that he’d squirrelled away at his home in Locust Valley, Long Island, has been unearthed and exhibited. The latest trove—more than five thousand small color snapshots made during the last three years of his life—forms the basis of “Please Send to Real Life: Ray Johnson Photographs,” an exhibition currently at the Morgan Library & Museum, accompanied by an excellent catalogue from Mack Books. Although many of his collage elements were photo-based, photography was never Johnson’s medium. In the case of these late photo works, it was primarily a means to an end—an easy way for him to document momentary interventions that he made in the local landscape. After constructing placards and signs in his studio, he’d place them on a parked car, a trash can, a cemetery, or a bench next to a life-size Ronald McDonald statue, and then take their pictures.

“Ronald McDonald with Tina Brown Movie Star,” March 31, 1993.

“tar seam in parking lot,” spring, 1992.

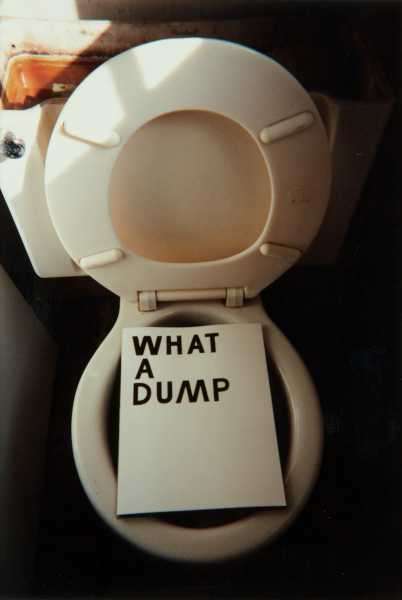

“WHAT A DUMP on the toilet,” March 1, 1994.

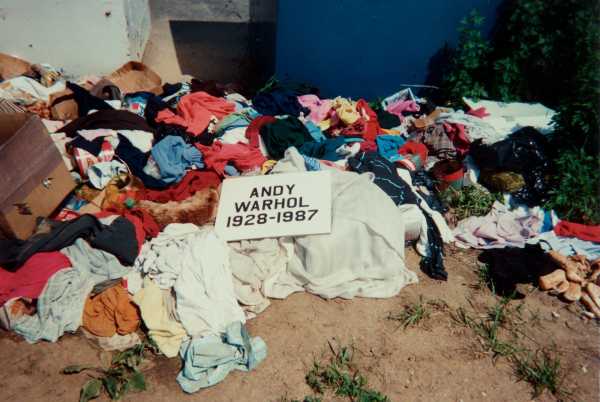

“Andy Warhol life dates on clothing,” May 31, 1994.

Some of the signs were simply hand-drawn, all-caps phrases: WHAT A DUMP (on an open toilet); ANDY WARHOL 1928-1987 (before a stack of funeral flowers and again on a pile of old clothes). More typically, Johnson’s texts were incorporated into cartoon-like drawings of his signature mutant bunny, which was variously labelled Max Ernst, James Dean, Horst, Long Dong Silver, and Pablo Picasso. The bunnies, together with portrait photos (often of Johnson himself), were arranged on long slats of corrugated cardboard, which the artist carted around and photographed in groups and individually, like totems or grave markers. Johnson referred to these as “Movie Stars,” and at the Morgan a number of them are set side by side on a high shelf, like a crowd of onlookers vying for attention.

“William S. Burroughs silhouette and kingfisher,” winter, 1992.

Even when Johnson avoided direct self-portraiture, his quirky fixations were always evident. (In an essay for the exhibition catalogue, the curator Joel Smith refers to “the low-key but constant thrum of odd motivation” behind all of the artist’s work.) In one of the collages on display, William Burroughs’s profile nearly eclipses that of the nineteen-fifties movie star turned gay icon Tab Hunter, and both are all but obscured by a swarm of pebble-like fragments and bits of collage. Johnson was forever constructing miniature sets for his own delirious theatre of the absurd: puzzles within puzzles. The sensibility is not unlike Joseph Cornell’s, minus the romance and period nostalgia. Johnson worked in another sort of outsider vernacular—at once banal, vulgar, campy, and deeply sophisticated. Like John Baldessari, he favored artless lettering and crisp graphic design. The cardboard slats, especially, might be mistaken for portable Baldessaris.

The Morgan show is based on previously unexhibited photographs—two hundred of which flash by on a video loop on the wall—but the curator is careful to provide examples of the artist’s use of the medium throughout his career. A photograph of Johnson at Black Mountain College, in 1948, opens the show on an unexpectedly tender note. It shows the artist from behind and in soft focus, so that his head, all but shorn of blond hair, looms in the landscape like a glowing planet. In other photos, he faces the camera, often in a photo booth, nearly always wearing a deadpan expression. No matter how present Johnson is in much of his work, he remained enigmatic and nearly impossible to pin down. The late photographs, all four-by-six-inch commercial prints, are full of information about Johnson’s daily life and the places he occupied or stopped in. None of these are especially revealing, though. Johnson’s take is reliably sly and allusive.

“tree trunk beside driveway,” April 7, 1993.

“palm frond on sand,” winter, 1992.

Sometimes, though, his landscapes—a cactus garden, a becalmed Long Island Sound, a broken palm frond, a shadow on the snow, and a roadside mailbox—seem in conversation with a whole school of photographers, from Walker Evans and William Eggleston to Wolfgang Tillmans, who all made the quotidian landscape and its fortuitous juxtapositions their focus. Johnson made this conversation explicit by name-checking or picturing Evans, Lee Friedlander, Duane Michals, and Richard Avedon—the latter pops up here in a picture on a book cover, which Johnson has topped with a pirate’s tricorne hat. There’s no question that Johnson knew the arena he was playing in, even if he was mostly happy to remain on the sidelines. In the guise of a suburban outsider, he continued doing what he’d always done so brilliantly, right up until the end: observing, commenting, sniping, and keeping it all to himself.

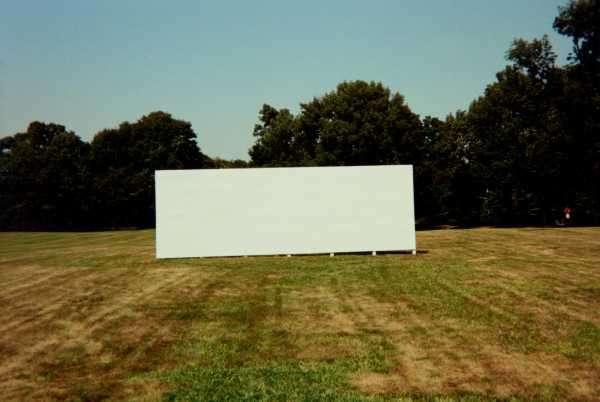

“billboard,” summer, 1992.

These photographs are drawn from “Please Send to Real Life: Ray Johnson Photographs.”

Sourse: newyorker.com