The text message came just before 7 A.M.: “Mandatory evacuation for the entire city of Malibu.” I grabbed my car keys, wallet, phone, laptop, writing stuff, and a change of clothes. It was Friday, November 9th. I was not worried. Malibu gets a fire nearly every year. Never do they creep down the Santa Monica Mountains, leap the Pacific Coast Highway, and take out homes where I live, in Point Dume.

But this one did. And it took out my home with an almost personal vengeance. Watching KTLA news with a friend in his Venice Beach studio the following evening, he pointed at the screen. “That looks like your house.” The camera zoomed in. “That’s definitely your house.” The shot—a firefighter blasting water at my inflamed bedroom—would play on repeat throughout the weekend. I became a kind of poster child for the Woolsey Fire.

The next few days threw into sharp relief my conflicted relationship with Malibu life. Many of my fellow-evacuees landed comfortably in Venice and Santa Monica. I received invitations to festive dinners and brunches at upscale eateries. Designer fashion labels offered free clothes to folks who’d lost their homes. A two-hundred-and-fifty-dollar gift certificate for luxury bedding showed up in my in-box. Compared to the extreme loss of life in the Camp Fire, it felt way too easy. Even in evacuation mode, we kept up our tenor of self-congratulation.

Meanwhile, I could not get back in to Malibu. Roads were closed on the north, south, and valley sides. The “stayers,” several of them surfer friends of mine, posted on social media about “never feeling a stronger sense of purpose” and “being honored to serve their community.” The Point Dume Bomberos, a vigilante group that formed in the fire, were saving houses. Supplies were coming in by boat; surfers were paddling them to shore on longboards. Malibu moms were cooking up hot meals in jury-rigged kitchens. I was hit with a sense of FOMO/shame. I’d got out of the fire, and now all I wanted was to get back into the fire.

I got in the following day with a makeshift press pass. Driving west past Surfrider Beach, the Pacific Coast Highway eerily quiet, I watched a set of waves peel across First Point, no riders. Malibu is one of the most crowded breaks on earth. The road closure would create empty lineups akin to the pre-“Gidget” days. I reached back and pawed the nose of my five-ten twin fin.

I passed places of great personal significance: the surf spot where I got my first tube, in 1978; the former home of the Malibu Inn, where in my tormented teens I consumed a half decade’s worth of soggy oatmeal and burnt coffee hoping to get closer to a particular waitress; the rocky outcropping where my late wife and I shared one of our last meals together, a picnic of cheese and avocado sandwiches, the shore break slapping and hissing below our feet. I started surfing in the late seventies. Malibu was my playground; it’s as close to my heart as any geographical place I can think of. But to be a surfer is to be a traveller. In my early twenties, I started travelling, and pretty much kept travelling.

The first sightings of the fire were just north of Pepperdine University. The charred hills took on a certain vulnerability, vegetation gone, trees skeletal, bald black curves in the midday sun. Born and raised in L.A., now fifty-two, I have come to understand that it’s essentially a race between the Santa Ana winds and the rain. If the rain comes first, the fire hazard is mitigated. But, if the fires come first, as they had now (and as they did last year, with the Thomas Fire and the ensuing mudslides in Montecito), we’re in big trouble.

A fire truck screamed past, behind it a S.C.E. truck, and behind that a Caltrans vehicle. Downed telephone poles obstructed the No. 2 lane. I’d been warned about hot power lines. To my right were charred black hills; to my left the blue Pacific shimmered almost smugly. I passed the former home of my friend Strider Wasilewski, a pro surfer, husband, and father of three young boys. The wooden A-frame, their dream home, had burned to the foundation.

I turned left on Heathercliff and left on Dume Drive, my street. Some homes were perfectly intact; others had burned to a physics-defying flatness. There was an odd randomness to it; you could almost see the embers flying over one roof and inflaming the next. The ugliest house on the block, a gaudy faux-Tuscan McMansion, still stood. I remembered the Voltaire quote: “God is a comedian playing to an audience too afraid to laugh.”

The homes leading up to mine were gone, and so were the homes across the street. I pulled into the gravel driveway and got out of my car. The burning smell was like a punch in the face. There was nothing left of the front house, a ranch-style home where my neighbors—a husband, wife, twin thirteen-year-old daughters, and two loud dogs—had lived. I followed the winding concrete footpath back to my guesthouse. It used to be shaded by a canopy of trees, but the trees were no longer. Ditto the surfboard rack that held a half-dozen prized boards. I’d never seen a burned surfboard before. The foam had disintegrated, but the fibreglass husks remained. They resembled shed skin, or cocoons.

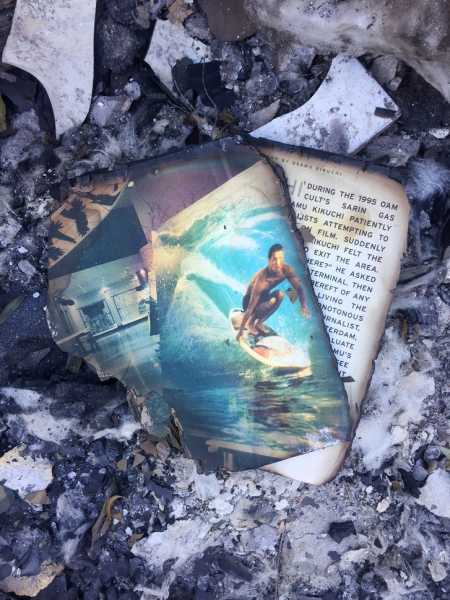

My house was pretty much what I expected: burned to the ground, save for the collapsing front wall. There were hot spots still smoldering. There were thousands of nails. I walked across the corner of the room where my bed used to be and rummaged through the jumble of charred books that had spilled from what had been a built-in shelf. The pages were scorched in a way that suggested the passing of time. They looked solid, but crumbled at the touch of my hand. I found some of my longhand writings on a legal pad. I unearthed a book and flipped to a picture of a surfer riding a blue wave, black char closing in on him from all four sides.

Photograph by Jamie Brisick

I did not feel some colossal sense of loss. It felt oddly familiar. In 2013, my wife of nine years died suddenly, in a cycling accident. After many years in New York, I moved back to Los Angeles with little more than a backpack over my shoulder. I crashed on my sister’s couch in Culver City. When the opportunity to live in a cheap guesthouse in Malibu arose, I jumped at it. Living in Malibu was a luxury I never imagined. I wrote, surfed, rode my bike in the hills above Zuma Beach. It felt almost too good. And, perhaps, having experienced firsthand the way our lives as we know and love them can disappear overnight, it felt temporary.

That evening, I gathered with other Malibu residents who had stayed around at the Point Dume Marine Science Elementary School. The parking lot had been turned into an emergency-operations center. Ash-covered firefighters lined up for chow. People I’d seen around town but never spoken to scooped up salad, rice, curried chicken, vegetables, cake, and ice cream. Smiles abounded. Hugs lasted a little longer. “How’d you do?” had become shorthand for “Did your home survive?”

I ran into a few of my surfer friends. “I show up and my house is gone, and there’s a spot fire in the house next door, and there’s a house—your house—burning,” my neighbor Keegan Gibbs told me. “Those immediate tasks, and that emotional connection with all these people.” He nodded toward our fellow parking-lot gatherers. “That’s what has allowed me to be O.K. with all this.”

“It’s nice to be appreciated for being a big, dumb guy with shoulders that can swing an axe for a couple of days,” a Zuma Beach resident Charles Smith said. Charles went on to tell me how, in the several dozen burned-down homes he’d encountered, nearly every one had some surviving memento or totem. “One house would have a little Jesus statue, the next would have a smiling, laughing Buddha. It was almost fated; the one thing that people needed to see had escaped the flames.”

Pretty much everyone gathered in that parking lot looked physically beaten down by the around-the-clock firefighting. But their spirits were exuberant. The sense of community, the sense of coming together for the larger good (corny as that sounds), was palpable. Normally, the big fish of Malibu are the rich and famous, the ones who own the five-million-dollar homes. The fire had turned this hierarchy on its head. These guys—these surfers—were the new heroes. At least for the time being.

Another surfer pal, Andy Lyon, walked up. Andy’s face was covered in ash. His boots were caked with mud. I’d been following his Instagram feed. He’d spent his fifty-sixth birthday putting out hot spots around his house, and ultimately saving it from burning.

“So sorry about your place,” he said.

“Thanks,” I told him. “But I’ll be fine.”

Andy gave me a knowing look. He knew there might be more to say, but didn’t ask.

Sourse: newyorker.com