The thirty-one-year-old photographer Robert Hickerson is an aficionado of horror films, choosing his props and color palettes from a canon of cult classics. For one of his first exhibitions, in college, he stretched opposite ends of a huge spandex tube over the faces of his mother and father, who’d recently divorced, and then filmed them trying to solve a jigsaw puzzle in the wan half-light of a living room. The Surrealist scene was inspired by David Lynch’s series “Rabbits.” Hickerson, who identifies as queer, relishes the gaudy Expressionism of genre films. He likes to describe horror as a “history of the other.” For the past decade, he has collaborated on much of his work with his mother and her spouse of sixteen years, a woman. The couple often turn over their suburban home for his editorial commissions and indie music-video shoots, letting Hickerson fill the garage with sand or burn a chandelier in the back yard. More recently, with Hickerson’s encouragement, they have appeared in front of the camera. A few years ago, after noticing a spate of anti-gay hate crimes in the news, the three of them dressed up to shoot a series about a family of werewolves who are terrorized in the night by intolerant village people.

“Death Approaches by Moonlight.”

“An Idea Strikes Loudly.”

Hickerson’s latest project is an ode to the campy brutality of “Suspiria,” the 1977 giallo classic directed by the Italian auteur Dario Argento. The film, which is one of Hickerson’s most formative inspirations, centers on an American dancer who travels to Freiburg to train at an élite ballet academy, only to discover that it is a front for a coven. The film’s plot is “intentionally ridiculous,” as the Times noted upon its première, but its style—distinguished by psychedelic lighting and lush bloodletting—helped earned Argento his reputation as the “Italian Hitchcock.” (A remake, directed by Luca Guadagnino and starring Tilda Swinton, was released in 2018.) Hickerson’s own series—titled “The Mother of Sighs,” after the name of the coven’s “black queen”—adopts the visual language of “Suspiria” to present a sumptuous retelling of the film’s creation.

“My Mother as Dario Argento (Screen Test).”

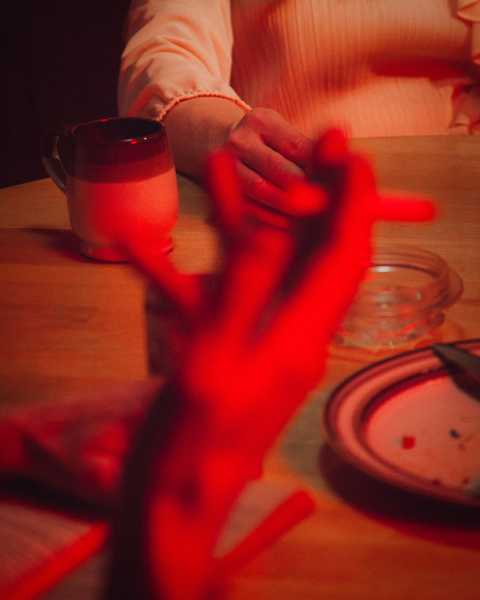

Many of Hickerson’s photographs mimic shots from the film’s set, in which Argento looms over actresses splayed in poses of death or duress. Hickerson dolled up his mother in a wig and facial prosthetics to play the gangly, shaggy-haired aesthete. In one image, she mounts a stack of boxes to fuss with a cord wound around the neck of a young ballerina who has caught on to the coven and been hanged through a stained-glass skylight. The original photos were shot in black-and-white, but Hickerson’s are rendered in the bruised blues and lurid reds of the film’s gloriously disorienting color scheme. They make a point of including Daria Nicolodi, Argento’s frequent collaborator and onetime wife, with whom he co-wrote the screenplay. Portrayed by Hickerson’s stepmother, Nicolodi has been slyly inserted on set, holding up a clapperboard at the edge of her famed husband’s mise en scène.

“Behind the Scenes III.”

Hickerson’s project strives, in part, to rescue Nicolodi’s influence on “Suspiria.” In a recent essay on the film’s “multiple authorship,” which Hickerson shared with me, the critic Martha Shearer argued that a preoccupation with Argento’s “status as an auteur” has demoted Nicolodi from the role of a co-creator to that of a mere muse. Nicolodi, who died in 2020, long insisted that the idea for the film was hers, going so far as to state that “everything belongs to me in ‘Suspiria.’ ” To magnify her artistry, Hickerson staged scenes of imagined sparring between Argento and Nicolodi. He and his mothers rented a spooky chalet in upstate New York, where the duo ad-libbed arguments about the script while Hickerson followed them around with his camera.

“A Short Night of Broken Plates.”

“The Shallow Threat of Six Pointing Directions.”

“Anger Saunters on High Heels.”

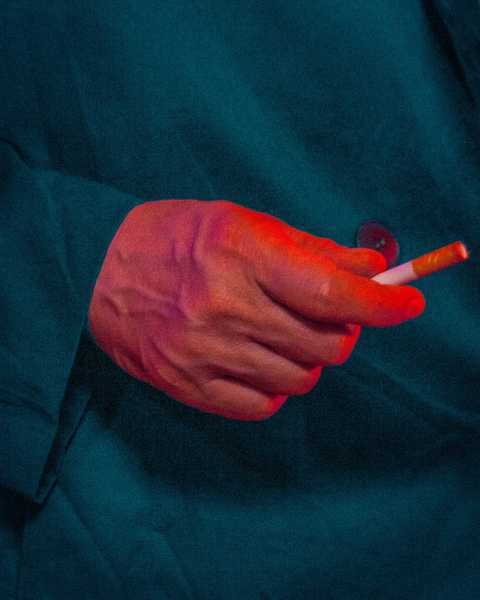

“The Mother of Sighs” broadens into a speculative exploration of the film’s origins, fixing Argento and Nicolodi in moments of artistically charged domestic strife. The couple exchanges glares as Nicolodi clears dirty plates from a dinner table. Later, while Argento sleeps, she steals outdoors to enjoy a cigarette in the dead of night, her frame backlit by the smoky glow of an arched window. The most striking images situate Nicolodi as different doomed students in the film. Like the protagonist Suzy Bannion, who roams the ballet academy after hours, roused by suspicions of witchcraft, Nicolodi skulks through Hickerson’s series in search of inspiration for her film. In one photograph, she stops to contemplate her reflection in black glass. The shot recalls an early scene of “Suspiria” in which the story’s first casualty, who has fled the dance academy, raises a lamp to a bedroom window to find bodiless eyes staring back at her. In “The Mother of Sighs,” black magic is not hokey witchcraft but the haunting force of an unrealized masterpiece.

“Death Is a Trilogy Waiting to Happen.”

“Perfection Solidifies in the Darkness of Night.”

“A Vice Made Fire.”

“Blood Drips Thicker Than Water.”

When Hickerson first showed his mothers “Suspiria,” he had to pause the film at regular intervals to warn them of coming gore. “They’re scared of scary movies,” he told me. For years, they were equally squeamish about appearing in their son’s work. Hickerson’s biological mother is a retired high-school teacher who now works in human resources; her wife is a corporate lawyer. The women came of age at a time when “queer” was a slur, whereas for Hickerson the horror genre has long represented “a queer safe space.” Hickerson told me, “They don’t have that experience, and I wanted to share it with them.” In shooting “The Mother of Sighs,” Hickerson hoped to show his mothers that the otherworldly elements of horror could be as freeing as they are obscene. In his earlier projects, the women’s faces were usually turned from the frame or obscured by masks. The “Suspiria” series is the first in which they face the camera. When I spoke with Hickerson, he was preparing to visit his mothers for a new shoot, about a demonic advertising agency. “My biological mom is going to be a vampire C.E.O.,” he told me, laughing. “They’re really into it now—but it took a while.”

“Burning Mask II.”

Sourse: newyorker.com