Leningrad in the nineteen-seventies was a closed, stultifying world all to itself, a microcosm of the Soviet Union: a universe of muted grays and beige, where nothing much seemed to ever change. An artist who existed outside the system had about as much a chance to get published or show his paintings as he did of strolling the grands boulevards of Paris. Sergei Dovlatov—a writer who would reach fame only in emigration, or more correctly, only in death—stewed in this milieu, a literary and artistic subculture of great intellectual vibrancy but which offered virtually no outlets to express it.

“Dovlatov,” which was released last March in Russia and in October, with English subtitles, on Netflix, is less a bio-pic than the evoking of a historical mood—albeit one with discouraging familiarity. At one particularly dispiriting moment, the film’s Dovlatov, played by the twenty-eight-year-old Serbian actor Milan Marić, is cheered up by one of the many women who float in and out of his life. “You know how much courage it takes to be nobody and be yourself?” she asks him. It is not so much a question as an invocation, a summons to an inner reservoir of humanity, a demand to not give in to lethargy, cynicism, and the ersatz success of the Soviet Writer’s Union.

“Me and my writing friends can’t get published, at least not the things that we were writing sincerely and in earnest,” Dovlatov explains in the film’s opening scene. “We are taboo.” Dovlatov would come to be one of the most beloved Russian writers of his generation, cherished for his unadorned, subtly comedic prose and wonderfully acute eye for all the poses and compromises and petty survival mechanisms on which humans rely. But in the seventies, the period shown in the film, he is a literary outcast, a virtual nonentity with no official career. Alexei German, Jr., the film’s director, has made a number of art-house projects that have been well received on the European festival circuit. With “Dovlatov,” he has made a deeply personal movie, a kind of cinematic letter and homage to his father, Alexei German, Sr., a Soviet director who struggled to have his movies made in the way Dovlatov failed to get his stories printed.

German, Jr., and I met for lunch in Moscow last spring, shortly after the Russian release of “Dovlatov.” We spoke about a scene at the end of the film, when Dovlatov has had yet another story rejected and has failed even at conformism, unable to produce a minimally suitable poem for a trade publication for Soviet oil workers. He sits on the floor in the hallway of his communal apartment, in a dark and hopeless mood—he appears doomed to the repeated frustrations of an author who can only “pisat’ v stol,” as the Russian saying goes, “to write for the desk,” or toil over stories that won’t end up anywhere but a desk drawer.

“Like Dovlatov, my father was also a big, strong guy, tall, with a large presence,” German, Jr., told me. “But when his film ‘Trial on the Road’ was forbidden from being shown”—the movie, about the redemption of a wartime traitor, complicated the official narrative about the Second World War, and was kept out of theatres for fifteen years—“he didn’t talk to anyone for three months, he just stayed laying in bed. It was a trauma.” In “Dovlatov,” German, Jr., presents that feeling of trauma with a tinge of romance—the poetry readings in cramped living rooms, the accumulation and discarding of both lovers and vodka bottles with equal listlessness, the long, uneventful, repetitive days with nothing to do but debate art and literature—a black hole that sucks up one’s energy and best years.

Yet seeing Dovlatov and his clique solely as victims, the passive subjects of an overbearing regime, is to miss the subtler truth of their existence outside society’s formal ideas about success and validation. Yes, Dovlatov and his friends had essentially no hope of official recognition, of being able to do work that both held meaning for them and fit with the paths for self-advancement on offer. (The film doesn’t soft-pedal the ugliness of this condition: in “Dovlatov,” a poet, repeatedly barred from publishing his work, slashes his wrist with a shard of broken glass.)

Yet to live in such obvious and unambiguous exclusion from the official system was also, in a sense, to be free from it. There was no career ladder to climb, no commercial reception to sweat over—all that mattered was one’s internal artistic motor, and the voices of a handful of like-minded and equally frustrated comrades. Dovlatov and his friends did not define themselves in opposition to the regime; even that act would offer it a form of recognition they couldn’t muster. And so, although they suffered under the Soviet state, they did not oppose it in the manner of Solzhenitsyn or Sakharov.

“You couldn’t call us dissidents,” Igor Yefimov, a writer and editor who was close to Dovlatov in Leningrad, said. Yefimov published Dovlatov at his émigré press, Hermitage, after they both arrived in U.S. in the late-seventies. “In our understanding, dissidents were people who pronounced they knew better than the authorities how things should be, how to rule the country,” Yefimov told me. “We didn’t believe we knew that. We were simply concerned with speaking and writing how we thought and felt.” German, Jr., told me something similar in describing what he sees in Dovlatov. “He is honest and truthful about everything, but talks about his country with love,” he said. “So many Russian writers tend to preach, but he simply converses.”

To remain apart from the binary of loyalty and opposition was a kind of workaround, a way to eke out a private space that functioned as a partial simulacrum of freedom, a life hack for late socialism. The Russian word for this state of existence is vnye, or being outside, though less in terms of the physical than the psychic. In “Everything Was Forever, Until It Was No More,” a brilliant study of the many paradoxes in the language and rituals of the last Soviet generation, Alexei Yurchak, a Russian-American professor at Berkeley, devotes a whole chapter to the concept of vnye. Yurchak defines vnye as the condition of “being within a context while remaining oblivious to it” and “simultaneously a part of the system and yet not following certain of its parameters.”

The paragon of vnye in nineteen-seventies Leningrad was Joseph Brodsky, the towering poet who would go on to win the Nobel Prize in Literature, in 1987. German, Jr.’s, film presents him and Dovlatov as intimate pals, brothers in literary angst, but that is a greatly exaggerated storytelling device. (Upon their arrival in America, Brodsky once chided Dovlatov for addressing him in the more informal Russian “ty”, rather than the formal “vy.” “What bullshit,” Dovlatov wrote in a letter relaying the episode to Yefimov.)

Nonetheless, the two writers indeed floated in the same circles in Leningrad, and Dovlatov observed Brodsky’s state of vnye in action. “He did not struggle with the regime. He simply did not notice it. He was not really aware of its existence,” Dovlatov wrote of Brodsky’s relationship, or lack thereof, to the Soviet state. “He was certain that Dzerzhinsky was alive. And that Comintern was the name of a musical group.” At one point, Dovlatov relays, the façade of Brodsky’s apartment building in Leningrad was decorated with a six-metre portrait of Vasil Mzhavanadze, a Georgian political boss and member of the Politburo in the sixties. Brodsky was confused. “Who is this?” he asked. “He looks like William Blake.”

Dovlatov was a much more human writer, and person, interested in the terrestrial world in all the ways that Brodsky orbited somewhere among the stars. “Brodsky made an appeal to the unknown, to the metaphysical,” Yefimov told me. “Dovlatov did not feel drawn to that side of life.” Dovlatov had a sharp and ironic eye for people, and for the absurdity of life that unites everyone in society, from prison-camp guards to newspaper editors to fartsovshchiki, black-market traders who sold everything from blue jeans to Nabokov. That inevitable absurdity is levelling and humanizing, binding us all together in a shared existence—this is the great insight, hilariously rendered, in my favorite of Dovlatov’s books, “The Compromise,” a loosely fictionalized account of his time as a reporter for a newspaper in Soviet Estonia in the seventies.

This was Dovlatov’s own form of vnye: an ironic detachment that allowed him to participate in society’s obligations while also gently mocking them. In “Dovlatov,” he is assigned to write a piece on a film the employees of a Soviet shipyard are preparing in honor of the launch of a new vessel. They dress up as Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky and offer canned greetings to Soviet citizens. Gogol, the factory’s mustached chief economist, has a weakness for drink, hitting the cognac on set before morning filming begins. Dovlatov’s bosses at the paper implore him to write a “sincere” article, but, in their vernacular, that means the opposite. Instead, Dovlatov writes a piece leavened with his own understanding of sincerity—that is, with humor and candor—which gets him fired. He diagnoses the problem faced by him and his circle of writers and poets and painters. “The things we were talking about didn’t exist,” he writes. “I mean, they did in real life. But the authorities pretended they didn’t.”

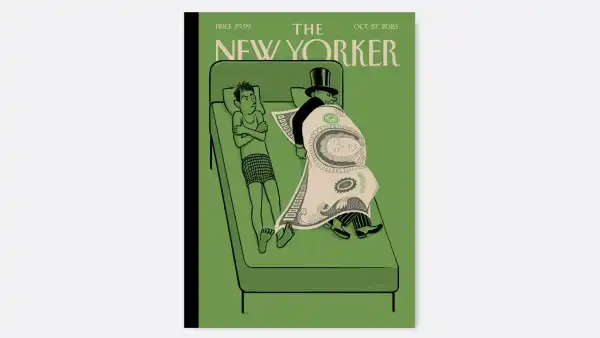

With time, the traits that kept Dovlatov from being published in the Soviet Union brought him success in America: not any sort of brave political stance but simply an acute eye for tragicomedy, an awareness of human weakness and self-delusion. Dovlatov loved a particular slice of the twentieth-century American canon—Faulkner and Hemingway and Salinger—for its plainspoken honesty, straightforward language, and lack of heavy-handed moralizing. Brodsky, who became a global literary sensation in America, introduced him to The New Yorker, where Dovlatov published his first story in 1980. He would publish nine more and a dozen books in English.

Dovlatov only became famous in Russia after his death, in 1990. (The Soviet Union outlived him by sixteen months.) German, Jr.,’s, film is further testament to his posthumous recognition at home, and a sign that contemporary Russian audiences find something relevant and instructive in his persona. When I saw the film in Moscow, last spring, the screening was followed by an audience discussion. People wondered what the lesson of Dovlatov and his circle was for those left feeling vnye in Putin’s Russia: How should an artist behave under authoritarianism? What are the constraints, and responsibilities, of that condition? Is the reach of the state ever escapable?

Nobody had any firm answers, other than to acknowledge all the ways that the Putin system differs from its Soviet antecedent: its demands on artists are, on the whole, more subtle and postmodern, allowing unencumbered expression in some niches while snuffing it out in others with behind-the-scenes economic and administrative pressure. For his part, German, Jr., bristled at the comparison in an interview with a Russian journalist. “If we were in the Soviet Union, you would have been fired for half the questions you asked me, and I never would have filmed anything at all,” he said. That may be true, but so are the prosecutions of the punk group Pussy Riot and the avant-garde theatre director Kirill Serebrennikov.

Dovlatov’s true subject, rather, is all the incredible and tragicomic ways people make do in whatever system they’re stuck with—the compromises and adaptations that make us all a little bit complicit, but, for that, entirely human. And that this humanity offers a refuge of freedom, however limited or imperfect, in a world that may offer little of it.

Sourse: newyorker.com