“Carousel,” now in revival at the Imperial Theatre, is the saddest of all American musicals. Twenty-four years ago, at Lincoln Center, I saw Nicholas Hytner’s fabled production, which was obviously cast for acting ability. As I recall, Hytner’s leads—Julie Jordan the textile-mill worker and Billy Bigelow the carnival barker—couldn’t sing or dance much. But they could act, and they made you feel what it must have been like to live as a dollar-a-week laborer in a coastal New England town in the late nineteenth century. Around the middle of the show, one of the actors says that there’s a big, limitless sky above them, and that, beneath it, they are just specks or sparks or something, waiting to be eliminated. How many times have you heard that sentiment expressed? But in “Carousel” it’s true. As the show opens, the sailor boys and factory girls, all of them looking to be about seventeen, are at the local carnival, having a happy night out. Then—oops—the curfew sounds, and the girls rush back to their dorm. Except one, Julie. She and Billy meet outside the fairground and confess that they’ve had their eyes on each other for a while now. They kiss, and, though there is no wind, blossoms fall from the sky. That’s Mother Nature speaking. The lights go out. When the lights go on again, both Julie and Billy have lost their jobs, and Julie is pregnant.

If Hytner’s production was for actors, the current revival, directed by Jack O’Brien, seems to have been created for dancers and singers, a logical choice given the cascade of heart-shredding songs created for it by Rodgers and Hammerstein. For the role of Julie’s kind, pie-baking, older cousin, Nettie Fowler, the producers snagged Renée Fleming, who, though she is probably still America’s most celebrated homegrown operatic soprano, was probably glad, at fifty-nine, to have something new to do. She gave the grand, Mormon Tabernacle-esque hymn “You’ll Never Walk Alone” everything it asked for, and those audience members who had not previously been digging in their pockets for a Kleenex were doing so now. But even more exciting, because the show is about youth, were the vocal performances of Jessie Mueller, as Julie, and of Lindsay Mendez, as her best friend, Carrie. When Mendez passed from her chest voice to her head voice in “Mr. Snow,” you practically fell out of your seat.

Renée Fleming, probably still America’s most celebrated homegrown operatic soprano, gave the hymn “You’ll Never Walk Alone” everything it deserved.

Photograph by Julieta Cervantes

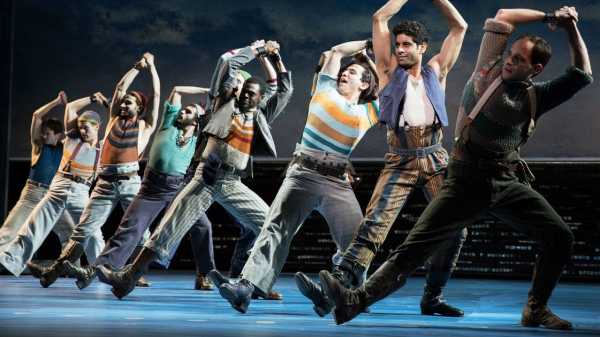

Almost as important was the dancing. I don’t know how much control the show’s choreographer, Justin Peck, had over the casting, but I’ll bet it was a lot, because the fabulous twenty-four-person ensemble was clearly chosen by a knowing hand. When the show opens, the carousel is staffed not by plaster horses but by dancers, and they give the scene a lift and a loft—ginghams, bloomers, jumps and turns forever—that does your heart good, and makes you very sorry when, like the youth and pleasure it symbolizes, it ends too soon. The ensemble’s other remarkable appearance—actually, it’s more remarkable—is the number “Blow High, Blow Low,” for the sailors on the wharf. Not since “West Side Story” have I seen such an unself-conscious display of hormonal fireworks. How happy these young men are to be young men!

Something especially moving here is the role that Peck created for Amar Ramasar, as Jigger Craigin, the man who lures Billy Bigelow into crime. Ramasar is Peck’s colleague: they are both members of New York City Ballet. (Ramasar is a principal dancer; Peck is a soloist, and the company’s resident choreographer.) Peck seems to have given himself the challenge of finding the very limit of what Ramasar could do. Surprise! He can act, he can even sing, and, boy, can he dance, heedlessly climbing over the wharves and jetties and wrecked old boats, king of his domain. He’s certain that the robbery he has planned will go fine. It doesn’t. He gets away. (Guys like Jigger always get away.) And Billy, in despair, cuts his own throat.

This was a new one on me. The Billys I knew had always done something less existential, like fall on their knives, and I think the purpose of the change was to add some heft to Billy’s role. Not that you fail to notice this Billy, played by Joshua Henry. For one thing, he is African-American, whereas his Julie is white. (The casting is color-blind.) But Billy doesn’t really have much to do in the second act. Basically, the women are the heroes of this show: Julie, Nettie, and, in the last section, fifteen years after the crime, Louise, the daughter whom Billy fathered on Julie before he died. These are the ones who walk through the storm, and in the second act the three of them, sitting in a row at Louise’s high-school graduation ceremony, reprise “When You Walk Through a Storm” to remind you of that. But, confusingly, much of Act II is about whether Billy, now that he’s dead, will be saved. He is, but why? What did he ever do but get Julie in trouble? (And hit her, a matter that the show does not throw a veil over.) For a while, he stands by as Louise—the excellent, leggy Brittany Pollack, another N.Y.C.B. dancer—performs a maybe-yes-maybe-no duet with a man (Andrei Chagas) who has wandered in. At the end, we see her doubled up and weeping, but the emotion governing the pair for most of their dance is vacillation. The same goes for Billy: he just sort of fades away.

This imbalance is typical of Justin Peck’s work. His group choreography is unbeatable. He seems to have known how to do it when he was born, so fresh it is, so natural, and yet so well made. But in his duets—which is where the center, the nut, of a ballet is usually to be found—there is something weirdly missing. And this has been true in many of his thirty-odd ballets. It’s as if he didn’t know what people do when they go home together. I’m sure he does, but the gift for showing this, like the gift for creating rousing ensemble dances, is not evenly distributed among choreographers. Maybe that’s O.K. for “Carousel”—the ensemble dances make up for a lot—but Peck is being discussed, among others, as a possible successor to Peter Martins, who recently retired as the artistic director of New York City Ballet amid allegations of various forms of misconduct. Interestingly, Martins, too, rarely managed to make much out of a duet. Peck can at least do group dances. But is that enough for the ballet company?

Sourse: newyorker.com