In 2014, Slate published ten photographs from a work in progress by the artist Brenda Ann Kenneally, documenting the lives of a group of twenty-first-century American teen-agers in Troy, a city in upstate New York. The subjects in her images were not doing much: in one, an obese teen-age boy lay on a mattress in a homeless shelter, disconsolate; an exhausted child at a kitchen table waited for his bottle to be filled with coffee, his favorite drink; a young woman named Kayla, one of Kenneally’s central subjects, smoked a cigarette as she held her baby son.

Some of Slate’s readers responded to these scenes with expressions of anger and disgust—they indicted the choices of the people depicted and accused Kenneally of exploiting them. Usually, people living in poverty are newsworthy only when their actions are criminal—meriting a few lines in a police blotter—but now it seemed that living was an offense in itself. The debate surrounding the work became the story, reducing the photographs with obfuscating commentary, like grime. The images had been in the public domain for years by then, but never in a way that could be so easily and thoughtlessly consumed. The attacks on Kayla’s parenting became so malignant that Kenneally asked that the photograph of her be removed.

Tony Stocklas was three months old when his mother, Kayla, returned to high school.

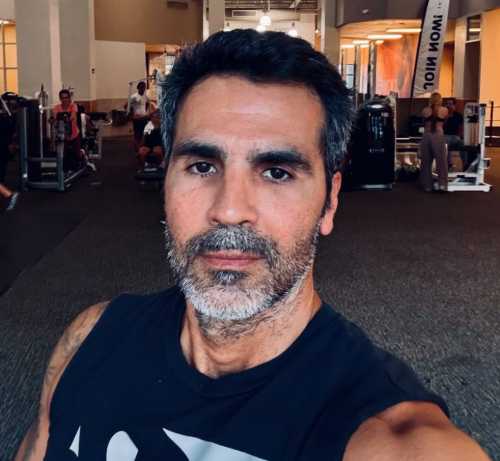

Kenneally was born in Albany, but she left the area when she was a teen-ager and didn’t return for many years. In 2002, she and I worked together on a magazine assignment that brought us to the city. She had recently finished a book that she’d been working on for ten years, about a community in Brooklyn. I had completed my own ten-year project, about an extended family from a poor section of the Bronx. Our upstate assignment, for the Times Magazine, stemmed from that work. Kenneally met Kayla on our first trip to Troy; after that, she couldn’t stop going back.

Big Jessie celebrated her twenty-third birthday with pellet guns, which were given to her by a girlfriend.

As she writes in a newly published book of the resulting work, “Upstate Girls,” Troy was once a wealthy industrial city, the kind of place that “embodied the idea of America as a land where every person’s dreams were realized.” But, by the time Kenneally was a teen-ager, in the nineteen-seventies, the industrialization that originally distinguished the city had contributed to its demise, as factories left the region to chase overseas deals. Except for one aunt, who became a teacher, no one in Kenneally’s family had any higher education. Kenneally herself quit high school and hitchhiked to Miami when she was around the same age that many of her subjects were when she met them. But she found her way to A.A. and then, through her sponsor, to photography; the process of applying to college, where she studied sociology and photojournalism, further transformed her life. All of this granted her enough perspective to keep her from being destroyed by misplaced shame.

DJ with her oldest daughter, Little Vic, on her prom day, in June, 2009.

Laurie with her son, Darien, and her daughters, Megan and Katie.

“Upstate Girls” has taken many forms over the years—hundreds of hours of video and audio, an archive of local vocabulary, collaborations with the local historical society, a nonprofit arts camp, even a museum. Kenneally launched the North Troy Peoples’ History Museum in 2016, with “Upstate Girls” as its inaugural show. The museum was housed in an apartment where several of her subjects had once lived, until the bank foreclosed and they had to move; their absentee landlord had stopped paying the mortgage. Other subjects had lived next door, and down the block. While Kenneally hoped that the museum might bring middle-class residents into a neighborhood they ordinarily avoided, and in so doing seed an exchange, she most wanted it to give the kids she’d documented a perspective on their own lives, and to do so in the places where both she and they had been raised.

Tony was in crisis—he was hyper, wouldn’t sleep or eat, and his medical trials had intensified. Playing video games was one of the only ways to quiet him down.

The show’s artifacts and ephemera included letters and art from incarcerated loved ones, receipts for furniture leased from rent-to-own businesses, prescriptions for the medications dispensed—in formidable doses—to the kids. One bedroom housed a library of scrapbooks made by the families who’d grown up in Kenneally’s photographs. There were also historical pictures of children in orphanages and in the crowded assembly lines on factory floors. A time line hung in the living room, like a monstrous mobile, tracking the decline in public health alongside once-lauded American products—tobacco, high-fructose corn syrup—and their code-switching, class-based marketing campaigns. These products had a particularly ruinous impact when they trickled down to North Troy residents, whose safety nets were being eroded by attacks on public education and other social supports. Kenneally had been studying inequality long enough to know that countering arguments about “personal responsibility” required that she expand the frame of her work to show exactly how lies about meritocracy cloak, and normalize, corporate greed. She obsessively gathered evidence—she calls it “hoarding”—to make us see these lives as she saw them, and to memorialize them as part of our nation’s history. At the Peoples’ Museum, this exhaustive contextualizing made it impossible to treat her subjects with contempt.

Terri and Big Jessie in their home.

Robert Stocklas on his twentieth birthday, after a fight with his baby’s mother.

The museum’s exhibition spread into every corner of the apartment, but it still represented only a portion of Kenneally’s sprawling multimedia archive. There are so many bodies in her images, in cramped back yards and on mattresses; exhausted, sleeping, loving, playing video games, dulled by pills, busting out, giving up, being born. So many bodies contained in physical spaces without enough light, or fresh air, or room to thrive.

While Big Jessie was in jail, her sister Stacey became pregnant.

Dasaun, Billie Jean, and Nanny Rose in the basement room at Deb’s.

Once shuttered and neglected, many of the buildings of Troy are now stirring again, reviving hope, as they are gutted and reclaimed by a wave of gentrification. Creatives—having pushed northward after getting priced out of Brooklyn—have begun making homes downtown. The young arrivals want the same thing that the subjects of Kenneally’s series want: a job, a home with a yard for the children, a safe neighborhood and a decent school, a place one can lay claim to. Is there a vision for the city sufficiently expansive to encompass former residents and newcomers alike?

During the winter of 2005, Kayla had been infatuated with Pops.

Dana Schubart nurses her baby.

Just as the book was going to press, one of the most ambitious young mothers in “Upstate Girls” was blindsided by the arrest of her husband, who is currently in detention, awaiting trial on numerous charges of rape and sexual abuse, including sexual assault of a child. (He denies them all.) Kenneally thought that “Upstate Girls” might be her parting gift to Troy, but this devastating news compelled her to return. She has been photographing the young woman—newly tattooed—and encouraging her to write through the crisis, to use art, as Kenneally had, to become an activist in her own life. How do we teach ourselves to fully apprehend the horrors we live among?

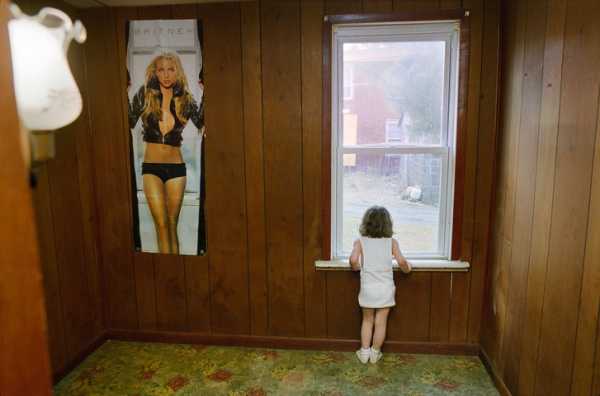

Destiny looks out the window of her new bedroom.

Shaming people who live in poverty is an old reflex in America. Kenneally reminds us that the fault lines of capitalism are everywhere within our nation, running through the very foundation we keep building upon. Her excavations blast through any attempt to deny it. In her book’s opening essay, she refers to her photographs as “new fossils.” With taking pictures, Kenneally writes, “comes the power to manufacture a record that future generations will consider fact.” Whether we choose to look or not, these images are facts.

Dana and Elliot in the supermarket.

Diana Jean lives with her mother, her two sisters, and her brother, in Troy.

Laurie’s daughter Katie found her Spider-Man costume among the boxes packed for the family’s move from their last apartment in Troy.

Sourse: newyorker.com