Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Robert Cumming, a pioneering wizard of West Coast photo-conceptualism, died in 2021, at the age of seventy-eight. He achieved brief semi-stardom in the nineteen-eighties, when he mounted solo exhibitions at both MOMA and the Whitney, but he failed to achieve the kind of lasting fame accorded to his close contemporaries in the L.A. scene, like Ed Ruscha, the master of deadpan Pop, or John Baldessari, Ruscha’s wackier counterpart, or even Cumming’s close friend and studio-mate William Wegman. Posthumously, though, Cumming has been experiencing a much deserved mini-revival. At Jean-Kenta Gauthier gallery, in Paris, a recent three-part series of exhibitions amounted to something like a retrospective. A new book, “Very Pictorial Conceptual Art,” edited by the writer and curator David Campany, collects Cumming’s photographic work from 1968 until 1980. The filmmaker Noah Rosenberg is making a feature-length documentary on Cumming, “On Closer Inspection,” a truncated version of which screened during this year’s Paris Photo art fair.

Cumming was born in Worcester, Massachusetts, in 1943, and raised in a technically minded family. His father was an electrical engineer. His siblings went on to work in medicine and nuclear science. When asked in a 2013 interview how he was inspired to become an artist, he responded, “I have absolutely no idea. I wasn’t aware that you could be an artist as a profession until I was a senior in high school.” But Cumming’s creative work was a weird science all its own. As an artist, he was an inveterate tinkerer who, for a period, taught himself a new fabrication skill every year, which would later come in handy when making the props that he used in his photographs. He was stubbornly inquisitive, often following his ideas wherever they led him, even—or especially—if it was impractical or absurd. Cumming is strongly associated with the West Coast, but he spent his early years as an artist living in New England, where he studied at the Massachusetts College of Art, in Boston, with a focus on painting. There he met Wegman, the future photographic jokester and Weimaraner portrait photographer, and the two promptly became creative companions. “Parallel play they call it, with children,” Wegman recalls in an interview in the forthcoming Cumming documentary. “So that’s who we were: artist children, parallel-playing. And we did very well together for many years without doing coffee-house arguing about the significance of what we were doing. Just that. And that’s quite wonderful, I think.”

“Bad Memories of Improper Electrical Application,” 1975.

“Decorator Test,” 1974.

“Foundations Students, Hartford Art School,” 1980.

Cumming and Wegman went on to grad school together at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, where Cumming learned photography with the landscape photographer Art Sinsabaugh and initially used the camera as a way to document his sculptures. But in the following years it dawned on Cumming, as it had dawned on photographers like Man Ray before him, that the documentation of his sculptures might be more interesting than the sculptures themselves. Wegman and Cumming both landed teaching jobs in Southern California, in 1970. At the time they shared a heady, hilarious approach to picture-making that was both thought-provoking and thoroughly unpretentious. What set them apart, though, was their execution. Wegman’s pictures were somewhat slapdash and perfunctory, in line with the “de-skilled” art of most photo-conceptualists of the day. Cumming, however, was almost preposterously exacting, making elaborate preparatory sketches when ideas came into his head, then manufacturing props as necessary and working with a cumbersome eight-by-ten-inch view camera to produce prints in astonishing detail.

“Watermelon/Bread,” 1970.

Cumming released his first self-published book of photographs, “Picture Fictions,” in 1971. On its cover was a work that would become one of his most famous, “Watermelon/Bread.” In it, the titular fruit rests on a patterned plate in a cluttered kitchen. The scene would be ordinary enough if not for the flank of the watermelon, into which Cumming has nestled a slice of store-bought white bread like some absurdist domestic Excalibur. The picture became something of an aesthetic calling card, encapsulating his work’s goofy rigor and strange cool. His creations seemed to invite the question, “What kind of person would bother to make such things?” (Cumming had a pithy rejoinder to such lines of thinking, saying, in a 1983 interview with Artforum, “In relation to singing toilet-paper dispensers and vitamin bottles shaped like Fred Flintstone, they’re often very usable.”)

In 1973, Cumming made a discovery that would reshape his creative approach: discarded collections of old eight-by-ten continuity stills from film sets, detailing what scenes looked like in between takes. The pictures were strange and often vaguely haunting; the spaces in them seemed to have been hastily abandoned in medias res, though a prominently placed director’s slate betrayed that there was artifice at work. Almost immediately, Cumming was inspired to convert his yard in Orange, California, into a kind of rudimentary studio backlot, where he would make artificially lit pictures by night. An emblematic work from this period is “Chair Trick,” showing a chair at the end of a garden path levitating above a piece of plywood. It doesn’t take more than a second to notice that the “trick” in question is rudimentary at best, and that Cumming made no effort to conceal the mechanism behind his illusion: a pane of glass propping up the chair, causing it to appear to float.

“Chair Trick,” 1973.

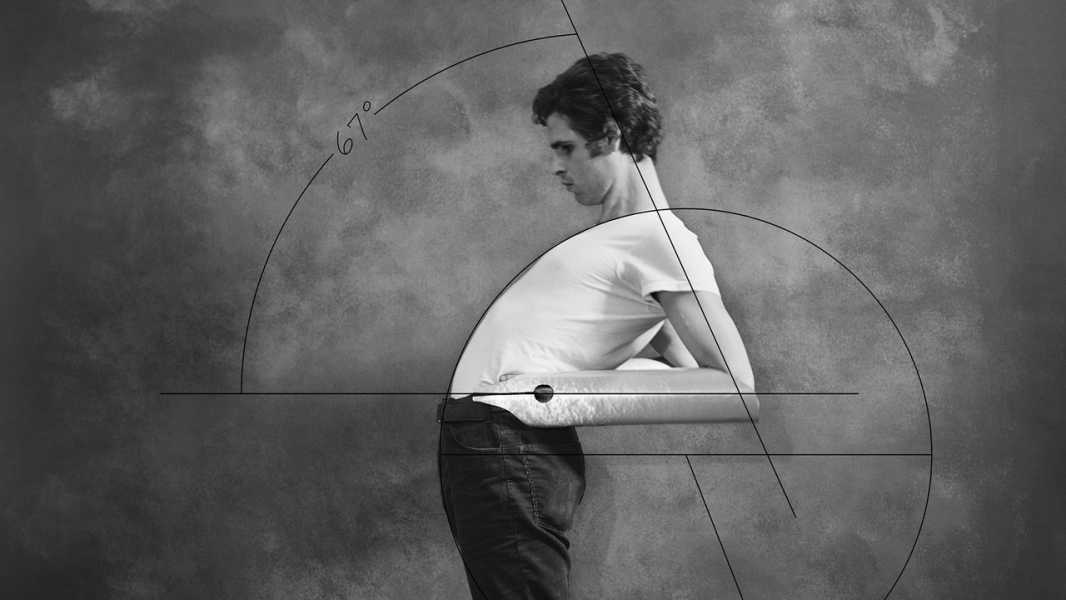

“I don’t do it to be funny,” Cumming said, in a 1976 interview, of this kind of hamfisted perceptual trickery. “I think a lot underneath the humor is it’s about perceptions, different types of perceptions, and that’s mainly what I’m after.” He was interested in the visual effects produced by the camera but also by its corporeal corollary, the eye. In one image, “Quick Shift of the Head Leaves Glowing Stool Afterimage on Pedestal,” for instance, what appears to be the ghostly silhouette of an industrial stool is, in fact, a spray-painted picture, with the can of paint left in the frame to prove it. The camera is able to capture a certain kind of “afterimage,” Cumming seems to say, but it is nothing like the one produced by our eyes. The humor, and perhaps the pathos, of Cumming’s work stems from its recognition that the apparatuses we use to comprehend the world are fundamentally imperfect, and subject to easy distortions.

“Quick Shift of the Head Leaves Glowing Stool Afterimage on Pedestal,” 1978.

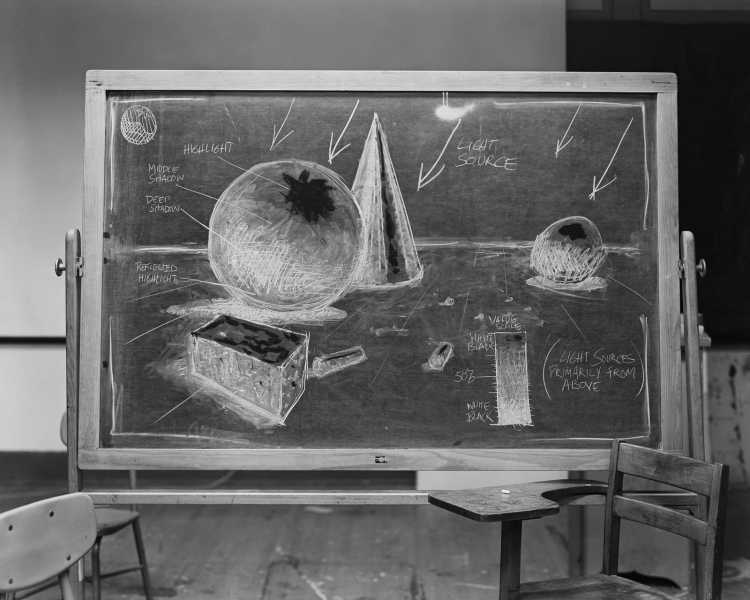

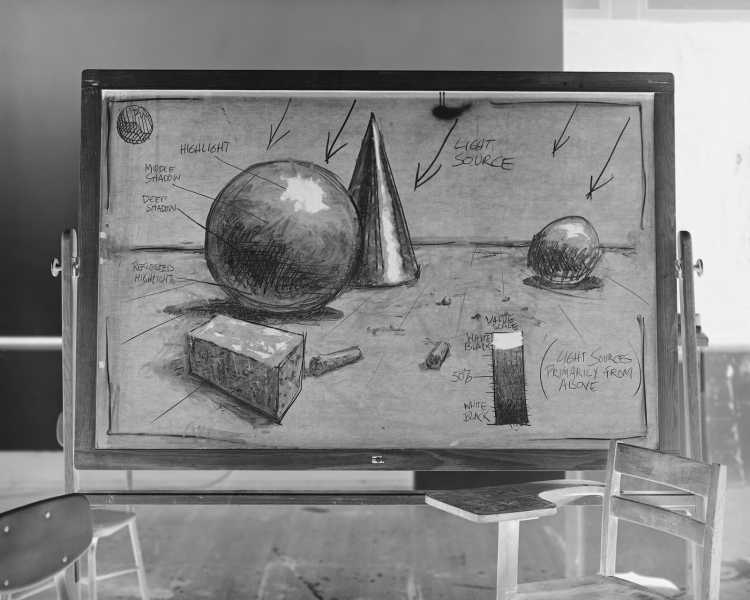

“Academic Shading Exercise,” 1975.

A photograph of a drawing.

“Snow Scene Under Construction; Feature Film, ‘It’s a Wonderful Life.’ – Stage #12,” 1977.

In 1977, Cumming was invited to photograph on the soundstages of Universal Studios, an opportunity that he grasped with vigor, making more than two hundred pictures in a matter of months. Long accustomed to the time-consuming work of staging and fabricating his images, Cumming now, for a series he called “Studio Still Lifes,” had a plethora of high-budget readymades at his disposal. A disembodied shark’s fin attached to a comically elaborate pneumatic submersible–a prop from the movie “Jaws 2”—looked like amped-up versions of his own eccentric fabrications. Other scenes, like ones of a faux-jungle landscape replete with potted tropical plants, shared the kind of wonky perceptual gimcrackery that marked many of his other pictures. But after his time at Universal Cumming found that his interest in what he called “the decadence of artificiality” waned. “It just felt kind of stale,” he recalled in 1983. “The whole thing of building models, staging photos, had become a routine.” Instead, he returned to his work in painting, drawing, and sculpture. When he did gravitate back to the camera, it was to make pictures of things out in the world—an airplane ripped apart by a tornado, a pair of half-melted giant snowballs, a complex piece of farm equipment—that just happened to look like scenes he might have contrived. If there is a message in these later photographic works, it might be that exposure to Cumming’s way of perceiving the world has a way of transforming the world itself.

“Farm Machinery,” 1980.

“Tornado Damaged C-133,” 1980.

Sourse: newyorker.com