Fifty years ago this month, hundreds of feminist activists, most of them from the political-resistance group New York Radical Women, arrived in Atlantic City, New Jersey, to protest the Miss America pageant. Marching along the boardwalk, the activists expressed their dissatisfaction with the pageant’s objectification and sexualization of its contestants—and, by extension, of women more generally—with signs bearing slogans such as, “Let’s Judge Ourselves as People,” “All Women Are Beautiful,” and “If You Want Meat, Go to the Butcher.” A sash-wearing sheep accompanied the marchers, as did a carnivalesque Miss America puppet, its face frozen in a rictus grin, and a “freedom trash can” into which women were encouraged to toss implements of feminine oppression: girdles, makeup, high-heeled shoes. Later, protesters stormed the pageant hall and unfurled a “Women’s Liberation” banner, after which several of them were arrested.

“The Miss America Pageant Protest,” 1968.

“The Miss America Pageant Protest,” 1968.

“The Miss America Pageant Protest,” 1968.

One of the protest’s attendees was Bev Grant, a twenty-six-year-old member of New York Radical Women, who not only participated in the action but also captured its unfolding in photographs. “Until 1967, I was leading a very conventional life, in terms of the role of women,” Grant, who is now a vibrant seventy-six, told me when I spoke to her recently. Originally from Portland, Oregon, she married young, and moved with her husband, a jazz musician, to New York, where she did “the cooking, the cleaning, and working at the same time,” holding a day job as a secretary. Joining a feminist consciousness-raising group that later merged into New York Radical Women proved decisive. “The women’s movement was life-changing for me,” Grant said, a bit wistfully. “I started to discover who I was—that I was worthy.” She separated from her husband and, in a move that she modestly describes as “happenstance,” learned how to take and develop pictures.

“The Miss America Pageant Protest,” 1968.

Grant joined Newsreel, a left-wing filmmaking collective, and went on to take thousands of black-and-white stills, documenting loci of political resistance in and outside of New York, from the sympathetic vantage of both participant and observer. But her career as a photographer was short-lived. By 1972, she had begun to focus on making music—first folk-rock, and, later, world beat—a medium through which, in the following decades, she expressed her ideological and artistic convictions. Her photos, meanwhile, remained unknown, many of them never even developed. Earlier this year, the curator and writer Alison Gingeras, who was researching late-sixties radical-feminist groups, was introduced to Grant and, in collaboration with the curator and editor Cay Sophie Rabinowitz, selected a handful of images, most taken in 1968, to exhibit at Rabinowitz’s East Village project space, Osmos.

“Rockefeller Center, New York,” 1968.

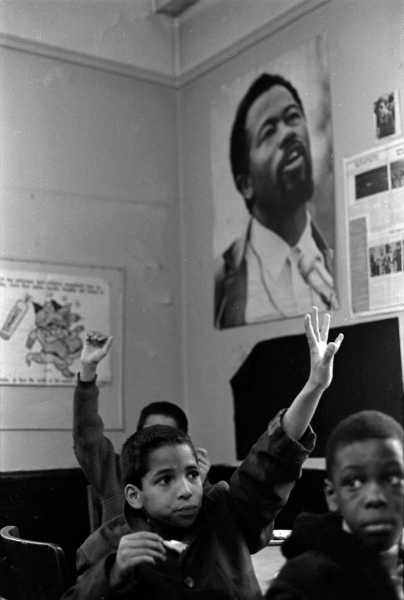

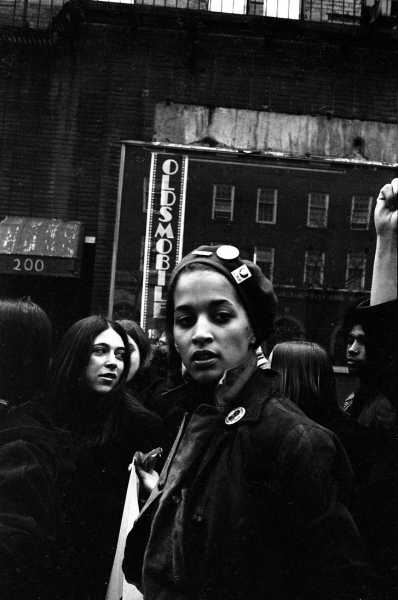

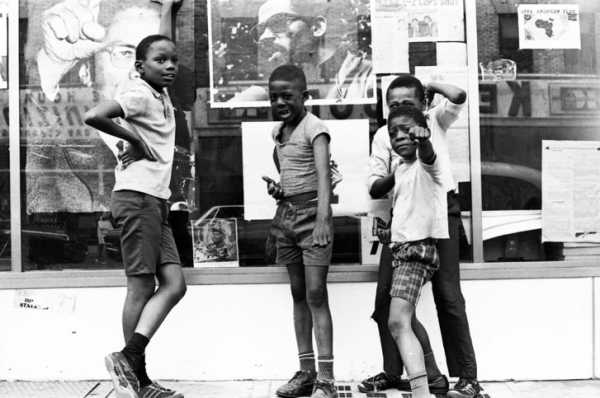

Grant’s first-ever exhibition includes several pictures from her Atlantic City Miss America series, along with other scenes of sometimes quotidian, sometimes dramatic strife. Through her work as a photographer, Grant told me, she was “exposed to different political struggles that were happening in the city and in the world, and it drew me into understanding my own oppression.” Meanwhile, her plight as a woman, she said, “helped me have empathy toward the things that were going on in the black community, and in the Puerto-Rican community. I understood the struggles of people different than myself.” In recent years, there has been an increasing reckoning with second-wave feminism’s exclusion of the concerns of women of color. (As bell hooks recalled, in 2014, “From the onset of my involvement with the women’s movement I was disturbed by the white women liberationists’ insistence that race and sex were two separate issues.”) Grant’s pictures, however, reveal an acknowledgement of a diversity of life experiences and ideologies within the protest movement. In one, a group of protesters, black and white, gather to call for the release from prison of the activists Ericka Huggins and Bobby Seale; in another, under a large portrait of a smiling Eldridge Cleaver, three boys dine on a free breakfast provided by the Black Panther Party; in another, a beautiful woman, a member of the Puerto-Rican Young Lords Party, gazes into the middle distance in the midst of a demonstration. Gingeras told me, “What struck me so profoundly was the fact that Grant prefigured this whole notion of intersectionality.” Grant’s images, Gingeras said, “tell the story of this utopic moment before things got very divisive and polarized. And the echoes of the struggles she documented are still being heard right now.”

“Poor People’s Campaign,” 1968.

A memorable humanism binds Grant’s images. Her subjects are coeval with, rather than subsumed by, their political action. When we look at a picture of a protester marching down an avenue, her skewed glasses are just as interesting as the anti-imperialist stance that she shares with her fellow banner-carrying demonstrators. “I never thought of myself as a quote-unquote photographer,” Grant told me. “I still have to turn my head when someone calls me an artist. But I do realize that I should stand up and be counted, and acknowledge that this was something I did that had value.” She paused for a moment. “I’m proud of the work, and I’m proud of my life.”

“Anti-Imperialism March,” 1968.

“Black Panther Party Free Breakfast for Children Program,” 1968.

“Joudon Ford, Minister of Defense for the Black Panther Party, Brooklyn,”1968.

“Young Lords Member Denise Oliver,” 1969.

“W.I.T.C.H. Hexes Wall Street,” 1968.

“G.I.s Against the War in Vietnam,” 1968.

“Boys in Front of the Black Panther Party Office,” 1968.

“Free Erika Huggins & Bobby Seale Demonstration,” 1968.

“Young Lords Party Garbage Offensive in El Barrio,” 1969.

Sourse: newyorker.com