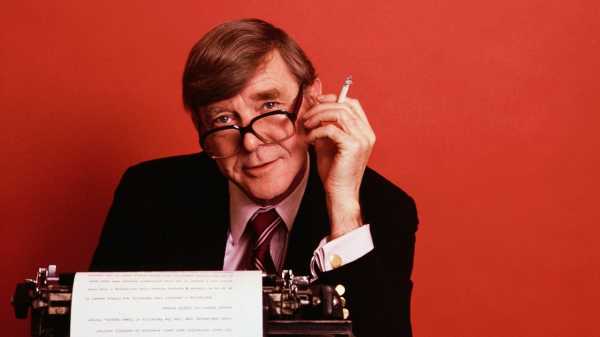

In August, 1968, Time magazine senior editor Peter Bird Martin persuaded managing editor Henry Grunwald to schedule a cover story about Russell Baker. Baker’s wry, self-mocking New York Times column, “Observer,” was carried by scores of newspapers across the country and was required reading for anyone interested in politics—broadly defined, well beyond Manhattan’s precincts—from 1962 to 1998. Baker would go on to win two Pulitzer Prizes, one for the column, in 1979, and another four years later for “Growing Up,” his best-selling memoir about his Depression-era boyhood. Baker’s column subjects ranged widely: from withering criticisms of President Lyndon Johnson and his pursuit of the war in Vietnam to Baker’s own inability to make it through a single volume of Proust; from the wretched excesses of the Super Bowl to the degradations of old age. Devotees used to say that the two best columnists at the Times were “Russell Baker serious” and “Russell Baker funny.” He died on January 21st, at age ninety-three, following a fall.

In 1968, I was the reporter for Time’s press section, and, after telephoning Baker to ask if I might come talk to him, I found myself on a train from New York to Washington, D.C. A taxi took me to the Dutch Colonial house, in suburban Washington, where the famously modest columnist lived with three cats, his wife, Miriam, known as Mimi, and their three teen-age children, Kathleen, Allen, and Michael. It happened to be his forty-third birthday; he was reading Saul Bellow’s “Henderson the Rain King” and smoking Kent cigarettes.

Baker immediately apologized for the length of my journey, because, he said, he didn’t have much to say about political humor. “People who commit humor can’t talk about it,” he said. “E. B. White has a great essay on how you can’t analyze humor. It’s true.” There was a long silence. Then he said that American humor, circa 1968, “owes a lot to the old New Yorker style—the humor of understatement. My writing in college was pretty much plagiarism of The New Yorker and [comedian] Fred Allen.”

A son walked by. “Hello, Allen,” Baker said. “Why don’t you go get a haircut?” The boy mumbled an indecipherable response and retreated.

I asked Baker if he had any lingering aspirations. “No, not really,” he replied. “Doing the column is comfortable. Secure. Though you’re never sure when people are going to start yawning. And it’s as close to what we fatuously call ‘creative writing’ as you can get. It’s good for my ego. But I’m constitutionally unhappy. Sure, I’d like to be out of journalism—write a best-seller and make a million dollars. The only justification for journalism is that you’re continually learning. You’ve got to keep learning. As far as the column goes, I’ve done it now awhile and I’m doing it as well as I ever will. So it, in itself, is not all that important. And I have no delusions that I’m influencing affairs—the journalist’s fatal delusion.”

Baker turned back to my assignment. “This kind of thing,” he said, meaning being interviewed, “is very distressing. Very depressing. You know the Socrates line, ‘The unexamined life is not worth living.’ I think there’s a corollary—if you examine your life close enough, you find it isn’t worth living.”

I suggested that perhaps he wore self-effacement as protective camouflage.

MORE FROM

Postscript

My Debt to Jonas Mekas

Mary Oliver’s Deep, Direct Love for the World

Becoming Francine du Plessix Gray

The Israel of Amos Oz

Super Dave, in Memoriam: Bob Einstein’s Mass-Culture Parody

The Improbable Life of Ray Hill

“No,” he said. “I’m really a very timid person, with the kind of face that people forget. I remember when I was doing police reporting in Baltimore, I was wanted for half the crimes; I fit every description. Even the name, Baker, is quickly forgotten.”

He looked glum, then brightened. “You probably want to know about my hobbies. Well, I’m afraid I can’t help you out much unless you count the time I collected stamps when I had the mumps. I’ve always been depressed because I never had a hobby. But I can’t do any of those things—carpentry, golf.”

Mimi, who had joined us, interjected: “You like to sit in the sand in Nantucket.”

“Yes, but that isn’t really a hobby. A hobby is uplifting. Like I read that David Brinkley does carpentry in the basement. I have a feeling he’s just copping out. He just tells that to interviewers.’’

I told him that, without a hobby, a Time cover was quite out of the question.

“Well, then,” he said. “Does it help that my high school ambition was to be a columnist? It says so in the yearbook.”

I told him that helped a little.

“And I once wrote a novel, when I was twenty-two. I wanted to satisfy myself that I could write a novel, so I sat down one summer and wrote ninety thousand words in six weeks. It was a terrible novel. I sent it off to a publisher and got the standard rejection note.

“Reston doesn’t have a hobby,” Baker added, referring to the longtime Times Washington correspondent, columnist, and editor James Reston.

I took the train back to New York and typed my notes into what Time magazine called a “file”—basically a memo recounting the interview. Ed Warner, the press-section writer, wrote the cover story, and within a week or two, it had gone through the line-editing, fact-checking, and copy-editing system. The story was laid out with photographs; cover art—an illustration of Baker—was commissioned and executed.

Because there was no urgency to run a cover story about Russell Baker and political humor, it languished for weeks, bumped by more pressing, newsier stories, of which there was a plenitude: Vietnam, riots in American cities, a Presidential campaign.

Finally the Baker cover was scheduled for the issue dated November 8th. On October 31st, it went to press. Several hundred thousand copies were printed.

Later that day, President Johnson announced a cessation of the bombing of North Vietnam. Time stopped its presses in the middle of the run, at great expense—a virtually unprecedented happenstance. An illustrated stop sign was quickly substituted for the illustration of Baker, and his story fell out of the issue. Baker would finally appear on the cover of Time, but not until the issue dated June 4, 1979, more than a decade later.

I telephoned Baker to tell him that he would not be on Time’s cover after all. I expected him to be crestfallen, as I was, but he reacted as if I had informed him that rain was forecast for the day after tomorrow. I could almost hear him shrug through the telephone lines. “Just as well,” he said. “Thanks for letting me know.”

Sourse: newyorker.com