Last week marked the fiftieth anniversary of the East L.A. “blowouts,”

in which thousands of Mexican-American high-school students protested

their crowded, understaffed classrooms and outdated textbooks with an

organized walkout. At the time, George Rodriguez was a

thirty-one-year-old photographer working at Columbia Pictures. It was a

good job, working on the publicity stills of stars like Frank Sinatra

and Jayne Mansfield. Rodriguez, who is also Mexican-American, had grown

up at a different time, and in a different part of the city—South L.A.,

not the Eastside, which was the hotbed of the burgeoning Chicano

movement. But he recognized that something important was happening.

During lunch breaks, he grabbed his camera and drove across town to take

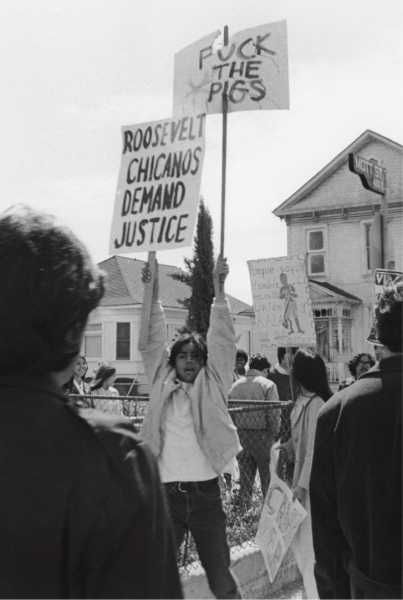

pictures. Who else would document this moment? One photo features a

teen-ager, his hair parted down the middle, holding a sign in each hand:

in the right, roosevelt chicanos demand justice; in the left, fuck the pigs. A visual

reminder, in light of the recent Parkland student protests, that

teen-agers have long been at the forefront of demanding political change.

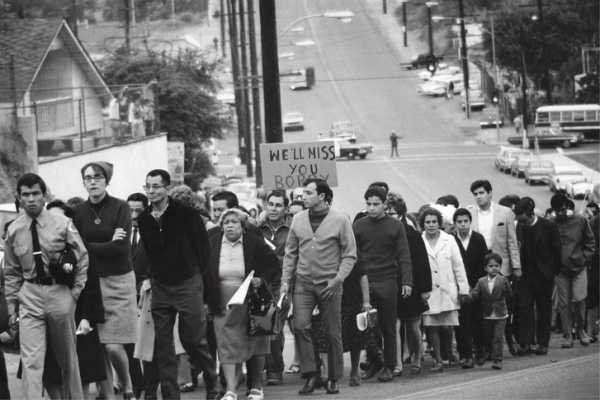

The student walkouts, known as “blowouts,” in Boyle Heights, 1968.

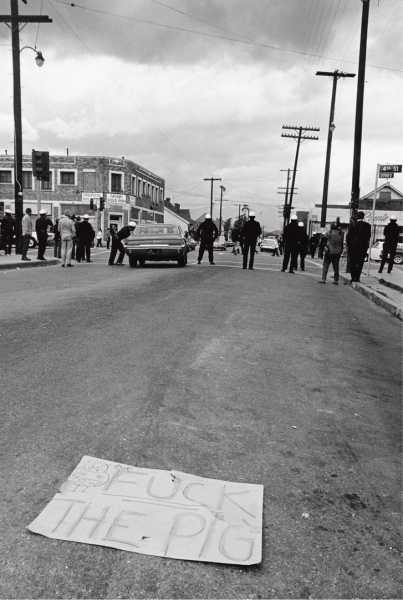

The Chicano Moratorium, an anti-Vietnam War demonstration, in East Los Angeles, 1970.

As Rodriguez’s career evolved, so, too, did his interest in these

seemingly disparate L.A. worlds: one fantasy-filled and glamorous, the

other gritty and politically attuned. He continued to work for studios

and record labels but also began working as a photojournalist, covering

protests, speeches, even the L.A. riots. As he later remarked, “I was

really living two lives.” “Double Vision: The Photography of George

Rodriguez,” a new book from Hat & Beard Press, puts these lives side by

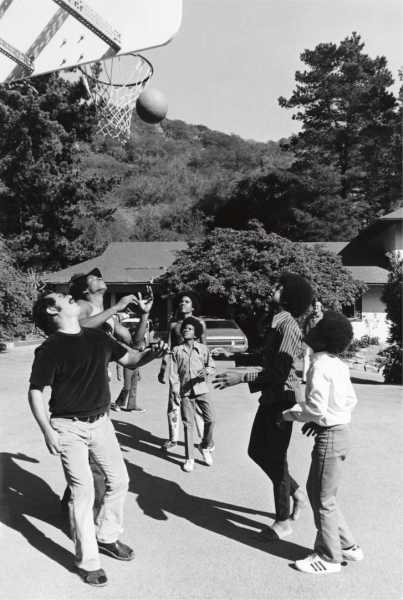

side. There are images of iconic performers: Van Morrison staring off

into space while jamming with the Doors; the Jackson 5 playing

basketball in the driveway of a house up in the hills; Eazy-E with a

“Compton” baseball cap, sunglasses, and leather gloves, trying to look

as tough as possible (a facing image, where you can see the rapper’s

soft eyes, might actually be more chilling). Rodriguez’s work is earnest

and professional, full of the angles and lighting tricks that make

people seem worthy of the album covers and magazine spreads he’d been

commissioned to shoot.

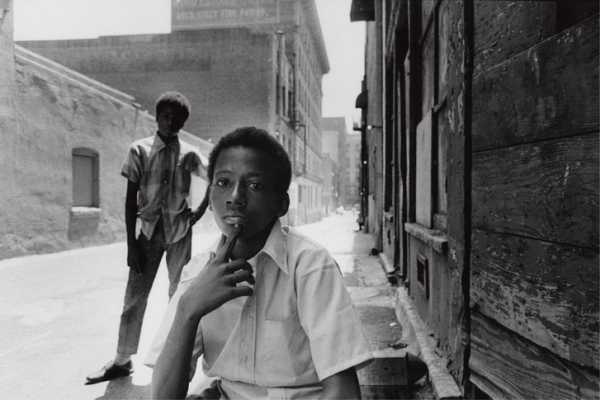

Los Angeles, 1971.

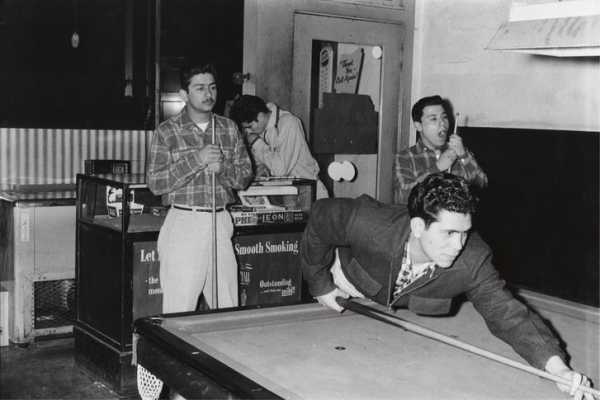

But there are also pictures of everyday people in Los Angeles: a man

leans into the welcoming light of a taco stand; a pool player, resting

on his cue, is caught with his mouth agape, mid-yawn; some black and

brown kids at a rally share a laugh on the side. In one particularly

rich image, Pete Wilson, the governor of California, stands at a podium,

addressing La Opinión, a Spanish-language newspaper; Antonia

Hernández, the head of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Education

Fund, sits to his left, her arms folded, head cocked, trying to destroy

him with her glare. “I was surprised someone named Rodriguez was coming

from the L.A. Times,” the civil-rights and labor activist Cesar Chavez

said when the photographer came to shoot him. Rodriguez ended up taking

an iconic picture of Chavez, in the hallway of his office, in front of a

campaign banner for the late Robert Kennedy, who had supported Chavez

and the farmworkers’ movement.

“In photography,” the scholar and curator Josh Kun writes, in his

powerful introductory essay, “double exposure typically refers to the

photograph, not the photographer.” It occurs when the film is bared to

light twice during a single shot, resulting in two exposures in a single

image. The effect can be surreal, like a haunting. Taken as a whole,

Rodriguez’s work offers a different kind of double exposure. In dividing

his attention between two worlds that overlap but rarely intersect, he

created one of the truest chronicles of Los Angeles there is.

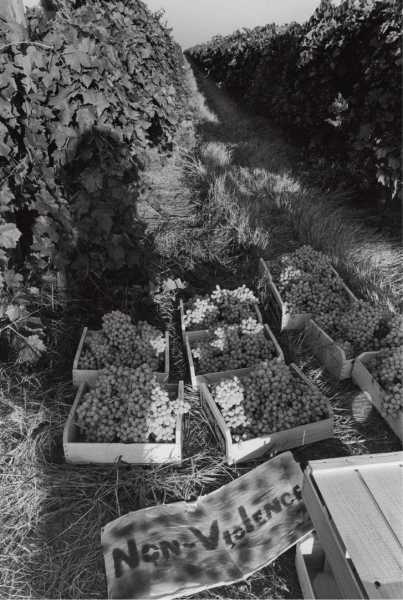

Mexican-American students in Delano, California, a hub for agriculture and the farmworkers’ movement, 1969.

Bravo’s Tacos in Los Angeles, 1970.

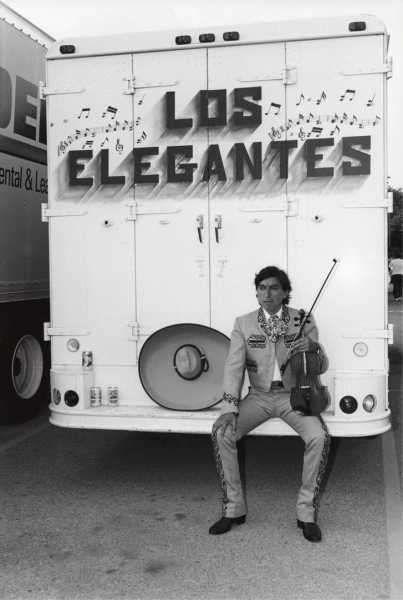

A mariachi musician in Pico Rivera, 1990.

Rudy Rodriguez with the Jackson 5 in Encino, 1971.

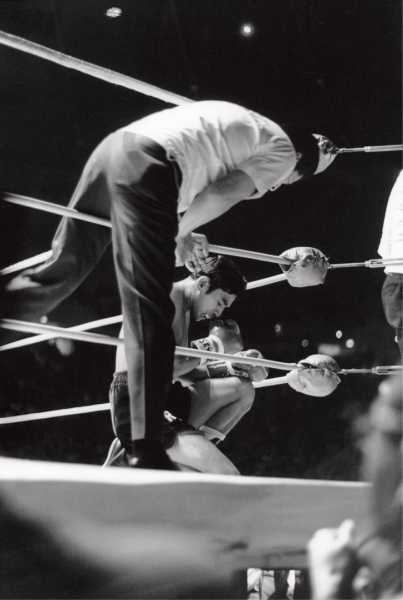

The boxer Rubén (The Maravilla Kid) Navarro at the Forum, in Inglewood, 1968.

The California governor (and former U.S. senator) Pete Wilson speaks to the staff of La Opinión in Los Angeles, 1994.

A farmworker boycott of grape growers in Delano, 1969.

Cesar Chavez in Delano, 1969.

A pool hall in Los Angeles, 1959.

A requiem procession for Robert F. Kennedy, who had supported the farmworkers’ movement, the day after his assassination, in East Los Angeles, 1968.

Sourse: newyorker.com