The Poison Squad: One Chemist’s Single-Minded Crusade for Food Safety at the Turn of the Twentieth Century by Deborah Blum, Penguin Random House, September 2018, 352 pages

We are living in a time when many see “deregulation” as a goal in itself. Red tape is obnoxious and counterproductive, and government should just leave businesses alone. That goes for an expanding array of consumer choices. When it comes to food, for example, an odd combination of the crunchy left and libertarian right now bridle at laws limiting their right to access “natural” commodities, like raw milk.

But they are complaining from a position of great fortune—an era when we can generally trust the food we are putting into our mouths. We take it as a given that our groceries contain what they say on the labels (and we have a right to raise hell if they don’t). I’m confident that my bread, for instance, isn’t full of plaster, and that my honey isn’t just corn syrup tinted with dye.

For earlier generations, this was not the case. There was a time when the government did little to regulate food production—and the results weren’t pretty.

- In Defense of Slow, ‘From-Scratch’ Cooking

- Time for Conservatives to Break the Anti-Environmentalist Mold

In the early 20th century, regulation of food focused on tariffs and weights, not whether what was in a jar labeled “honey” had ever been near a bee. Producers were not obliged to reveal ingredients and consumers took their chances, sometimes paying with their lives. Deborah Blum’s forthcoming book explores how food laws in America were created largely through the work of one man.

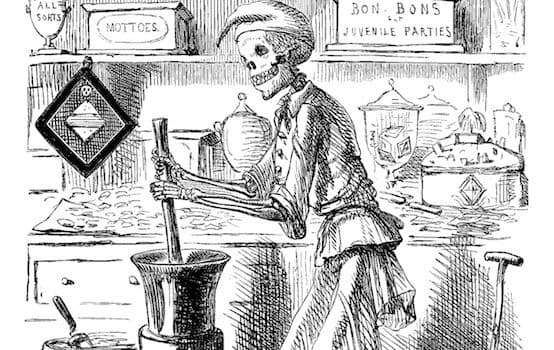

The Poison Squad is about Harvey Washington Wiley, who dedicated his career to trying to improve food safety. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, there was little limit on what could be sold as food (or medicine). Packaged foods commonly included lead, dirt, straw, and various toxic chemicals. These substances were a result of sloppy manufacturing, or deliberate admixing, to save money and/or make products last longer.

I only made it to the second page without gagging. There Blum explains how milk was often adulterated in the late 19th century. It was watered down, and chalk or plaster powder was mixed in to get the color right. To replace the layer of cream on top, pureed calf brains could be used.

The public were not oblivious to the fact that food was often tainted. Books were even published giving instructions on how to test for food fakery, using simple kitchen experiments. But there was not a lot they could do. When samples of candy were tested, for instance, over 90 percent of those on the market contained dangerous levels of arsenic or lead. Cake frosting was similarly risky. Reading about how food was adulterated does give a different spin to reading Edith Wharton—imagine all those fancy candlelight dinners, full of bromide salts, with arsenic in the candies, dirt in the coffee.

Given the amazingly high rate of food adulteration, it is possible that many consumers had never even tasted the real flavor of most common foods (coffee in particular tended to be full of chicory, flour, sticks, and dirt; tea was padded out with random leaves, grass, and dye). The rate of contamination was partly the fault of modern food supply networks. Urbanization and industrialization created the conditions for fatal contamination on a mass scale because food from one dairy or slaughterhouse might be distributed widely across the country. Meanwhile, the necessity of transport over long distances meant producers turned to dubious methods of synthetic preservatives.

In the case of milk, formaldehyde was a favored option. Commercial products such as “Preservaline” hit the market for precisely this purpose. Added to fresh milk, it could prevent curdling for days, the same way it could preserve dead bodies. Sadly, it didn’t have quite the positive effect on the living children who consumed it. Clusters of child deaths in various cities in the late 1890s turned public attention to what was being put into milk. Blum suggests dozens of children died, particularly those in orphanages and hospitals, which bought the cheapest supplies.

Along with man-made toxicity, agricultural products carried the risks of various natural pathogens in the flesh and soil. Slaughterhouse practices—exposed by Upton Sinclair in The Jungle—were unsanitary beyond belief. Rotting meat was mixed with fresh, the whole place was awash in e.coli and salmonella, and some unwitting consumers were even supplied human flesh along with their ground beef when an unlucky worker fell in front of the machinery.

But industrialization also offered the solution to the crisis. The mass media could generate efforts towards public health and raise awareness. Modern lab equipment could test for impurities. For milk, a solution existed: pasteurization. It was already mandatory in some countries, but U.S. producers resisted on the grounds of cost and hassle. No, it would not allow old milk to stay shelf stable for weeks without refrigeration (something some of the dairy firms were obviously seeking when they used formaldehyde). But it would save consumers from the risks of salmonella, listeria, campylobacter (then known as “infant cholera”)—not to mention formaldehyde itself.

Blum offers a chronological survey of how Wiley, a chemist by training, worked within the Department of Agriculture to clamp down on contaminated food. He faced strong resistance from industry (no surprise) and sometimes from lawmakers (particularly those who represented agricultural interests). But he was aided by the popular press, which made him a national figure for his fight against tainted food.

Many producers saw government regulation as an infringement on their freedom of contract—a similar argument had swayed the Supreme Court in Lochner (1905), which held that laws restricting working hours were against the free rights of the worker. Makers of adulterated food felt that citizens should have the right to purchase what they wanted without government interference (never mind that most consumers had no idea what was in the food they bought, or much choice in the matter).

This is not to say all producers hated the idea. Heinz was one major company that saw a marketing opportunity rather than a threat. They found that pasteurized foods packaged in sterile containers lasted longer than those made with chemical preservatives. They were tastier, too. So Heinz began to focus their advertising on their products being free of heavy metals, formaldehyde, and other additives. Many smaller producers, tired of being undercut by unscrupulous competitors, were also supporters of plans to regulate food production. The “pure food” plan worked for Heinz: even before the safe food laws were passed, they were beating their competition. This suggests perhaps that the market (and consumer awareness) could have driven out the shady operators, but it probably would have taken a much longer time and who knows how many lives.

Fast forward 100 years, and what Wiley campaigned for—packaged, inspected, sanitized food—is now cast by some as an unnecessary government intrusion. Critics rely on the image of some soft-focus imagined past when people ate a healthy “natural” diet. (From a business perspective, the profit that can be made from the word “organic” today means it’s hard to blame those who have jumped on the bandwagon.)

On the health food side, there have been plenty of advocates of raw or unpasteurized dairy and other products, with predictable results. For example, Odwalla used to market their juices on the idea that unpasteurized was more natural and tasted better—until they were responsible for an e.coli outbreak that killed a child and forced them to face the fact that germs are real and pasteurization works. But this image of idealized “natural” food only exists today because of men like Wiley. Because all of us have grown up with the luxury of a safe food supply, we don’t know what it was like for people to regularly die from botulism or child cholera. A clear parallel exists with vaccine attitudes—only those who have come of age since polio ceased to be a threat can be blasé about vaccination.

Case in point: activists use the phrase “real milk” to distinguish something straight from the cow from “fake” milk, which has been pasteurized and can be bought by the carton at your local supermarket. Amazingly, claims are even made for the health benefits of raw milk for pregnant women and small children, when they are among those most vulnerable to food-borne pathogens. I guess they can experience “Real Campylobacter,” too.

According to the CDC, no more than 1 percent of milk consumed in the United States is raw, yet there are more illness outbreaks linked to raw milk than there are to pasteurized milk.

Today we needn’t worry about arsenic in our favorite candy or that the steak in the butcher shop might not be from the animal we thought it was. Blum provides a list of dramatis personae at the front, which is very helpful—there is a large cast of politicians, lobbyists, and scientists over the decades that the book spans. While the narrative at times gets caught in the weeds of who said what to whom and which ballroom of the Denver Grand hotel hosted the meatpacking industry’s annual meeting, it provides a contextual counterpoint to today’s deregulatory zeal. Wiley’s tenacity is one we should celebrate as an American success story.

Katrina Gulliver is a historian who has written for The Spectator, TIME, The Atlantic, Slate, Reason, and The Weekly Standard. Currently she is working on a history of urban life. Follow her on Twitter @katrinagulliver.

Sourse: theamericanconservative.com