“The Yamamoto family values were forged in small spaces,” the Japanese photographer Masaki Yamamoto told me recently. For eighteen years, his family of seven coexisted in a one-room apartment in Kobe. His father drove trucks, and his mother worked as a cashier in a supermarket. They and their five children all slept in the same space, a room the size of six tatami mats, limbs overlapping amid a pile of ever-multiplying junk. When you looked up, you couldn’t avoid meeting the eyes of someone else, Yamamoto, the second-oldest of his siblings, said, adding, “The one place you could be alone was the bathtub.” “Guts,” his new photography book, is a celebration of his family’s everyday existence in these close quarters.

In the West, Japan is often characterized as an island of loneliness—of family-renting industries, of sexless youth, of the unwanted elderly shoplifting out of a longing for the social comforts of prison. At first glance, Yamamoto’s photographs might seem to provide further evidence of a claustrophobic solitude. In one image, his sister sits in the bathtub, her thin knees folded close to her chest, a Rodin immersed in a tiny tub filled with milky water. It is a sombre scene, until we read the caption and find that she had jokingly drawn her knees up so that she would look like she had huge breasts.

The Yamamoto family.

The power of Yamamoto’s photos lies in this subversion of the viewer’s expectations. Yamamoto is clear-sighted and un-nostalgic about his family’s precarious economic circumstances. When he was eight years old, the family was evicted from their previous apartment in Kobe. They all lived out of a car for a month, and Yamamoto and his siblings spent time in a children’s home before being reunited with their parents. In one photo, Yamamoto shows his mother playing rock, paper, scissors with her husband, to decide whether their money should go to his pachinko games. The camera focusses on the bills clenched tightly in her fist. Yamamoto also confronts the difficulties of growing up with little personal space or privacy. He told me of his sister’s struggles with hikikomori, the Japanese word for becoming a social recluse and refusing to leave the home; his younger brother dropped out of high school. “And there’s a thing called puberty,” he added.

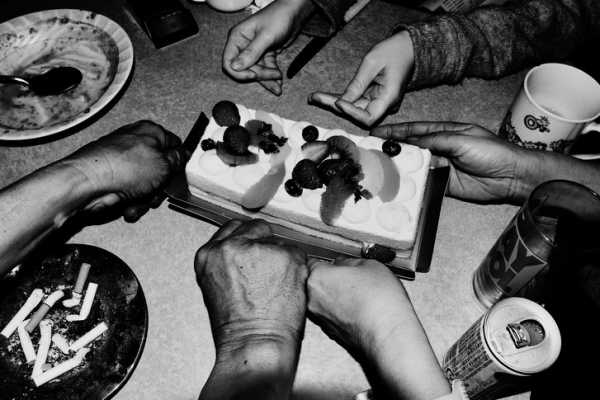

Fighting over who gets to cut the cake.

At the same time, Yamamoto said that he’s drawn to photographs that seem to say, “Yes, we’re poor, but.” His photos are distinguished by his subjects’ performative, gleeful lack of self-seriousness. Through his lens, his family members are competing jesters in their one-room kingdom. Sons and mothers enjoy moments of playfulness, cheek against cheek. “I take photos when I’m laughing,” Yamamoto said. “When they’re in front of me, when they’re behind me, when we’re all laughing.”

Mother and son.

Upon seeing the Yamamotos’ domestic clutter, the viewer might instinctively wish for Marie Kondo—the Japanese empress of decluttering—or for dozens of Hefty bags. To feel that, and then to question that feeling—while witnessing the ease with which the Yamamotos find joy amid their mess, in the thinginess of things—seems, to me, an integral part of entering Yamamoto’s world. A mother licks melted mochi off her fingers, and her family, and the viewer, delight in how disgusting it looks. A few pages later, she stretches out alongside her daughter, next to a pile of unwashed dishes, empty shochu cans, crinkled newspaper, and drying orange peels, to play video games. In Yamamoto’s black-and-white images, I sense a gentle but prickly anti-Kondo spirit, a Japanese world far more dynamic than Kondo’s bourgeois one of bare white walls and tidy, unpeopled floors. In one photo, Yamamoto’s mother carefully applies her makeup while looking in a mirror resting on top of the barbecue hot plate used for the previous night’s dinner; in another, Yamamoto is busy witnessing the bonelike beauty of a calcified apple, forgotten for months underneath a bed.

“My younger sister gets her hair cut at home.”

Last year, after a lifetime of living in budget apartments, Yamamoto’s mother found a leaflet advertising a real house, with two floors and Western-style toilets, for a rent they could afford. After they moved, the first thing his mother did, Yamamoto said, was to paper their new bathroom walls with his photographs of their former apartment, “so that they will never forget the spirit of the Yamamoto family.” Within two days, the photos peeled off of the wall, sticking in large, loose rolls onto the bathroom floor. His mother eventually put them away, with grand plans of pasting them up again. But she can no longer find them, he said. His photographs are now lost, part of the accumulating stuff of their new home.

“My little brother trying to prove that he can dive underwater for one whole minute.”

“My father shaves his head in the kitchen.”

Playing video games.

An average afternoon.

“Failing the one-minute diving challenge, my brother pops out of the water.”

“My mother doing her makeup on top of an electric hot plate used for grilling meat.”

Leaves of a Japanese radish growing near the kitchen sink.

“My younger sister puts her knees up to make it look like she has big breasts.”

“My younger sister eats ramen from the pot.”

“My little brother after a surgery on his eyelids.”

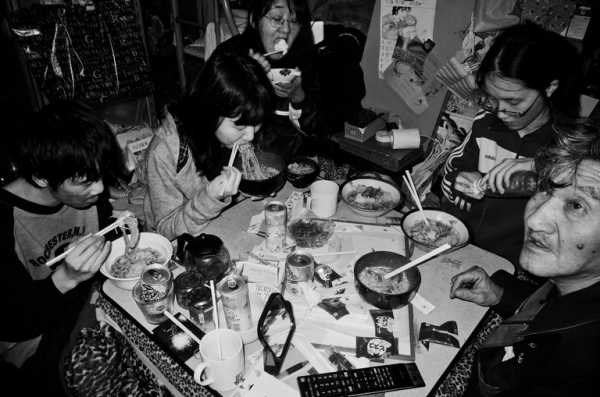

Eating “year-crossing noodles” on New Year’s Eve.

“My father and mother play rock, paper, scissors to decide whether he gets an extra thousand yen to play pachinko.”

“When my little brother went to night high school, he liked to take his time in the mornings.”

“My mother licking her hands stuck with sticky rice.”

“My mother takes a picture of her eye after retinal-detachment surgery.”

“My eldest brother caught a yellowtail and brought it home.”

Sourse: newyorker.com