Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

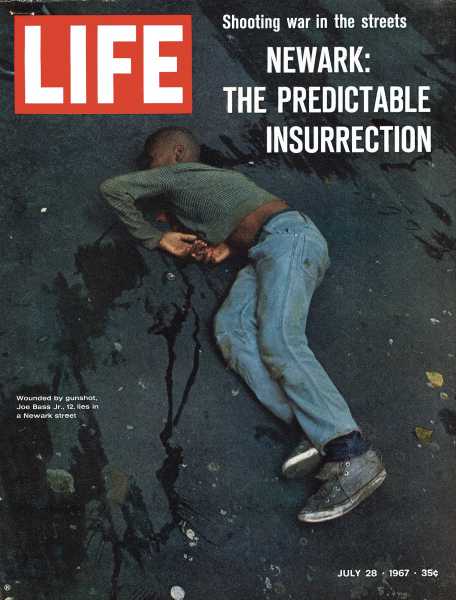

In a photograph that appeared on the cover of Life’s July 28, 1967, issue, a twelve-year-old boy named Joey Bass, Jr., lies contorted in the middle of a street in Newark, New Jersey. His bluejeans and high-tops look stained—muddied, perhaps, from playing in the grass earlier that day. Blood pools around him, following a jagged course on the concrete beneath his body. The magazine’s logo, in the top-left corner, partially obscures the boots of a hovering police officer. Bass was wounded that summer as Newark law enforcement attempted to suppress an uprising sparked by the beating of a Black cabdriver. After the unrest began, on July 12th, the police director Dominick Spina, through the city’s mayor, had asked Governor Richard Hughes to deploy state police and the National Guard. Hughes instituted a citywide curfew, and Spina, in a chilling directive issued over police radio, instructed his officers to use a gun if they had one. “This is a criminal insurrection by people who say they hate the white man but who really hate America,” Hughes told the Times. In the end, twenty-six people died over a four-day period, while hundreds more were injured; no officers were ever indicted.

Bud Lee’s photo of Joey Bass, Jr., a twelve-year-old wounded by police gunfire, on the July 28, 1967, cover of Life. The image won Lee a News Photographer of the Year Award in 1968.

The family of Joey Bass, Jr., at their home in Newark.

The photographer who captured Bass, Jr., for the cover of Life was Bud Lee, a twenty-six-year-old who had spent the past three years as a military photographer for Stars & Stripes before being recruited to Life by Peggy Sargent, the magazine’s photo editor. Prior to the Newark assignment, he had been dispatched to document the first legal abortion in the United States, in Denver. (The magazine never printed the images.) On the day he was assigned to cover the events in Newark, he had been shooting a portrait of a Wall Street stockbroker. The summer meant a dearth of other available photographers, and he was asked to step in, accompanied by the reporter Dale Wittner.

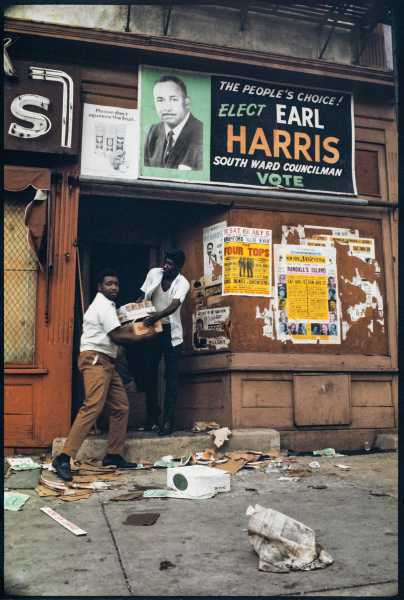

Billy Furr (right) and friend hauling cases of beer out of Mack Liquors on Avon Avenue.

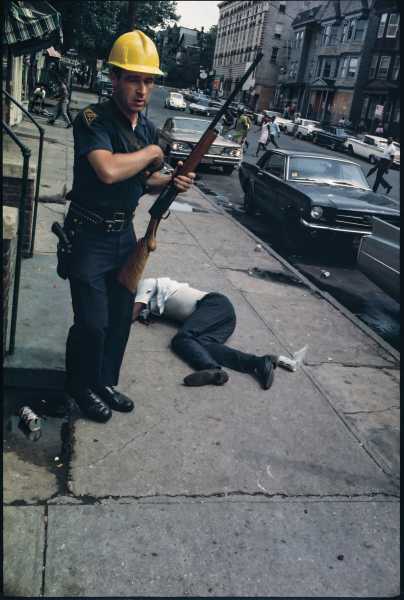

A Newark police officer stands over the body of Billy Furr.

A National Guardsman sleeps in a Newark storefront.

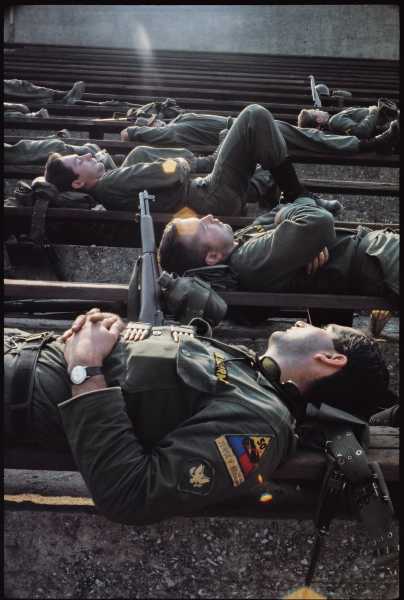

National Guard soldiers sleeping on the bleachers at the Newark Schools Stadium.

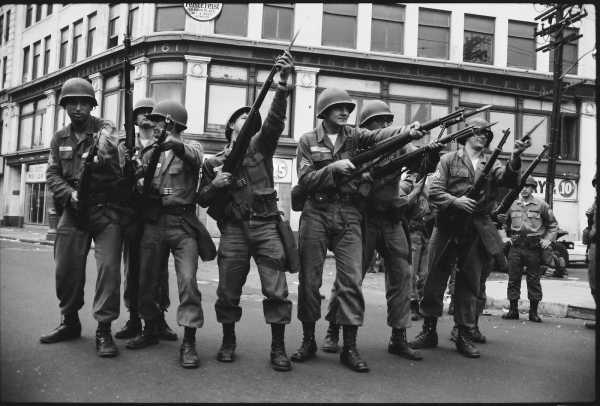

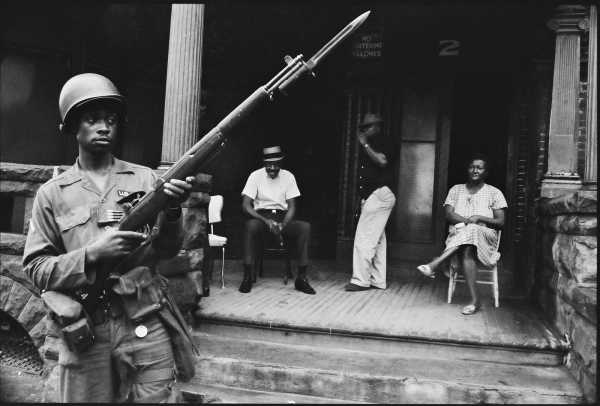

A book of Lee’s images from Newark, titled “The War Is Here,” was recently published by Z.E. Books, drawing on a large archive of unpublished photographs that Life returned to his family in 2016. (Ras Baraka, the mayor of Newark, provides a foreword in which he recalls that his father, Amiri Baraka, was detained during the uprising and struck over the head by a police officer who had once been a schoolmate.) In Lee’s pictures, the young soldiers of the National Guard appear bemused, with Newark’s landscape stretching out before them like a foreign war zone. They nap in storefronts and lie on bleachers. In one image, they stand with their bayonets pointing in the air, trained on an invisible target.

Lee studied painting at the Art Students League of New York, the National Academy of Design, and Columbia University, and cited the landscape compositions of the Dutch master Pieter Bruegel the Elder as an influence. Newark was the first time he shot in color, working exclusively on color slide film rather than the more common color negative. The journalist Chris Campion, who edited the new volume, notes that this allowed less flexibility when shooting documentary photography. But this technical disadvantage produced haunting results. A photograph of Bass’s family at their home in Newark is underexposed in a way that evokes oil painting, and its subjects are posed in almost Mannerist style: mother, her gaze fixed somewhere in the distance, a cherubic baby in her lap; father, reclining in a chair; two children at his feet, and one standing at the back. All of their bodies are elongated and partially illuminated by a lamp, which casts one half of the picture in brightness. Only Bass’s sister, on the floor, seems to be looking at the camera lens, perhaps sensing the strangeness of the situation—the unsettling notion that, as in the magazine cover image of her wounded brother, Black pain has to be seen to be believed. In another photo, taken during a press conference at Baraka’s Spirit House, James Rutledge, Sr., the father of a young man shot thirty-nine times by Newark police, holds aloft a picture of his son’s lifeless body. Lassie, the boy’s mother, is photographed looking downward, with a black veil shielding her face.

Lassie Rutledge (right), the mother of James Rutledge, Jr.

James Rutledge, Sr., holds up a photo of the body of his nineteen-year-old son, James Rutledge, Jr. The young man was shot thirty-nine times by police.

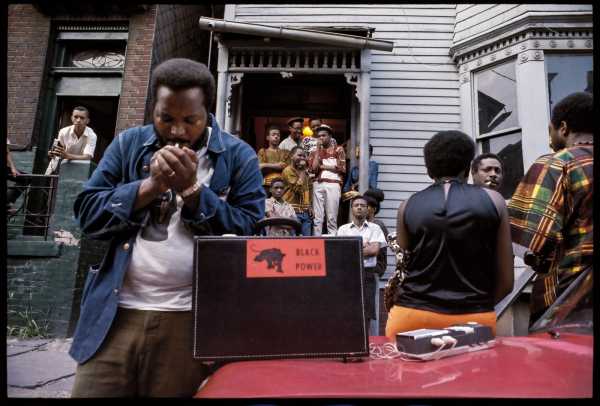

Outside Amiri Baraka’s Spirit House in Newark’s Central Ward, during the first National Conference on Black Power, in July, 1967.

After Lee’s Newark assignment, Life sent him to cover the unrest in Detroit in July, 1967, and the funeral of Martin Luther King, Jr., in 1968. “I was like their golden boy,” Lee later remarked. Eventually, he grew weary of documenting so much national trauma. He went on to photograph the scene around Andy Warhol’s Factory and worked briefly as an on-set photographer for Federico Fellini and Arthur Penn. In the early seventies, he was sent by Esquire to Los Angeles, to cover the city’s occult scene after the Manson murders. Around this time, he experimented with drugs and experienced thoughts of suicide. “He ended up having a bad acid trip,” his son Thomas, who oversees his archive, told me recently. “He was looking for a way out of that whole life.” After undergoing treatment at a veterans’ hospital in Iowa City, Lee settled in Florida, where he became a schoolteacher and lived until his death in 2015.

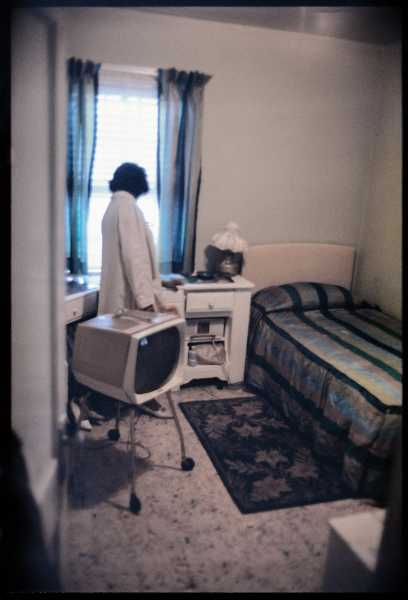

According to Lee’s widow, Peggy, Lee remained “haunted” by what he had seen in Newark. That summer, he had photographed a twenty-four-year-old named Billy Furr outside of a looted liquor store as Furr and other men carried out cases of beer. When a squad arrived, Furr ran up the block. Police fired at Furr, killing him and wounding Joey Bass, Jr., in the same spray of bullets. On the final day of Lee’s assignment, he visited the Montclair home of Furr’s mother, Joyce. In one photo, she stands in her son’s room looking out the window. Her back is turned to the camera, and the walls are unnervingly spare. The bed is made, but with a slight depression on one side that suggests the recent presence of a body. Joyce’s hand rests on a table, as though she is steadying herself. She is waiting.

Joyce Furr, the mother of Billy Furr, stands at the window of his room in Montclair, New Jersey.

Sourse: newyorker.com