Fifty years ago this week, the Democrats held their National Convention in Chicago (August 26th to 29th), an assembly torn apart by pro- and antiwar factions in the hall and violent clashes in the street. It was the convention that, in effect, turned the country over to Richard Nixon and led to six more years of war in Vietnam. From a contemporary point of view, the only element that redeems the event from complete sorrow is the scathing and poetic book that Norman Mailer wrote about it, “Miami and the Siege of Chicago,” one of the essential works of American reporting.

Mailer got going as a political reporter in 1960 when he covered the Democratic National Convention that summer—the Kennedy convention—for Esquire. His piece was called “Superman Comes to the Supermarket,” and it caused a sensation. Here was this hipster intellectual and novelist from New York, immersed in the city’s literary life, in the Beats, in Dostoevsky and Hemingway and Faulkner, facing down the great American dullness of delegates and mediocre speeches and the booze-and-cigar fog of compromise and bargain. What was he doing among such fellows?

A convention is a gathering of established and occasionally insurgent people from big cities, suburbs, and small towns, and from all levels of income and power. For Mailer, it was fascinating—the faces, the bodies, the voices, the sound of crowds, the décor and smell of the gathering places, the backwash, the undertones, the unconscious of the event. The very ordinariness of convention politics was richly significant if you bothered to wonder what it all meant. Mailer unlocked his powers of evocation, and, by the time he was done, no one, not even the wrathfully witty H. L. Mencken, had ever written of political people—both hacks and powers—with such uproarious verve, with so tactile a command of surfaces and so great an interest in the national mysteries. Mailer had the richest sensibility in American prose (Gore Vidal, by contrast, seems dryly witty and ungenerous). In this report, Mailer functioned as a critic of souls.

At the center of the convention, there was John F. Kennedy, who was something of an enigma—an unknown who nevertheless gave hope:

Kennedy seemed at times like a young professor whose manner was

adequate for the classroom, but whose mind was off in some intricacy

of the Ph.D. thesis he was writing. Perhaps one can give a sense of

the discrepancy by saying that he was like an actor who had been cast

as the candidate, a good actor, but not a great one—you were aware all

the time that the role was one thing and the man another—they did not

coincide, the actor seemed a touch too aloof (as, let us say, Gregory

Peck is usually too aloof) to become the part. Yet one had little

sense of whether to value this elusiveness, or to beware of it. One

could be witnessing the fortitude of a superior sensitivity or the

detachment of a man who was not quite real to himself.

Seven years later, with Kennedy dead and the country in turmoil, hope had become fleeting and ever more precious. In October, 1967, Mailer went to the March on the Pentagon—an ebullient protest against the war in Vietnam—and produced his nonfiction masterpiece, “Armies of the Night.” The text was composed of two enormous magazine pieces (for Harper’s and Commentary), and I’m hardly alone in considering it one of the great American books. Despite Mailer’s despair over the war in Vietnam (four hundred and seventy-five thousand Americans were there in late 1967), “Armies” is an amazingly sprightly book. At the Pentagon, the intellectual and spiritual heart of the antiwar movement (the political people, the professors, the students radicals) were joined by hippies from New York and California reciting Hindu chants—an attempt to levitate the Pentagon three feet off the ground and cleanse it of its evil. Why not try it? Nothing else had stopped the Vietnam War. The march was propelled by an antic spirit of creativity and daring. Mailer was charmed by what he saw; stirred, too, by the courage of the resisters, some of whom stayed the night and got clobbered in the morning by military police. He was even moderately pleased with his own behavior, since he did not run from the police but charged into their midst and got himself arrested.

In “Armies,” Mailer thrust himself into the narrative as actor as well as observer. It was the halcyon days of the New Journalism, when such writers as Tom Wolfe, Hunter S. Thompson, and Truman Capote used fictional techniques to make narrative journalism come alive with temperament, observation, and opinion. But Mailer’s writing reached heights of complication that the others didn’t try for. As an observer attentive to everything, he was hit from moment to moment with new perceptions, which changed his consciousness as an observer, forcing him to make still fresh observations and new distinctions—a positive feedback loop whose results were closer to Faulkner and Joyce and Whitman than to journalism of any kind. The writing was literally inimitable.

The hopeful mood did not survive the dreadful Spring of 1968. First, President Lyndon Johnson announced that he would not run for another term (March 31st), which produced a moment of euphoria. But that blessing was followed, in merciless succession, by the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., (April 4th); riots in more than a hundred cities; students at Columbia University erupting (April 23rd), which ended with the cops beating heads; and the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy (June 5th). By summer, the country seemed to be unravelling. In early August, in a reactionary attempt to ravel it back up again, the Republicans held their convention in Miami and nominated Richard Nixon and Spiro Agnew. The Democrats followed, and nominated Hubert Humphrey and Edmund Muskie. Humphrey, the former liberal lion, could not bring himself to break with L.B.J. and turn against the war, an intellectual and moral failure that doomed his campaign from the start.

Settling into Miami, Mailer savages the humid city, a place that had once been a wilderness (“The vegetable memories of that excited jungle haunted Miami beach in a steam-pot of miasmas”). Then he goes to work on the Republican delegates, the Nixonites:

Their bodies reflected the pull of their character. The dowager’s hump

was common, and many a man had a flaccid paunch, but the collective

tension was rather in the shoulders, in the girdling of the shoulders

against anticipated lashings of the back, in the thrust forward of the

neck, in the maintenance of the muscles of the mouth forever locked in

readiness to bite the tough meat of resistance, in a posture forward

from the hip since the small of the back was dependably stiff, loins

and mind cut away from each other by some abyss between navel and hip.

Such rigidly sexless people, Mailer says, were locked into their belief in an American infallibility blessed by God, and they couldn’t begin to question the war. They couldn’t even see the war; Nixon helped them not see it. But then Mailer gives the devil his due, noting with chagrin (many of us felt it) that Nixon was intelligent, sometimes subtle—the 1968 version of him was an improvement over the obvious phony and opportunistic anti-Communist demagogue he had started out as twenty years earlier. Mailer prints excerpts from Nixon’s acceptance speech, engaging in a line-by-line dialogue with it. Not all of Mailer’s remarks are satirical or hostile, and he leaves the convention in a puzzled state. Was Nixon evil or not?

The Chicago section begins with a description of the city’s magnificence. The architecture, the river, the blood-drenched stockyards (which were then still open)—Mailer outdoes Upton Sinclair in the mucky poetry of slaughter. The stockyards were not so far from the International Amphitheatre, where the convention was held, and the fabulous Mailer nose, which never slighted an interesting odor, registers the acrid scents of butchery. It is the first of many apocalyptic metaphors. L.B.J. controlled the Democratic machine for his fawning Vice-President—the nomination was never in doubt—but the convention was still a very disorderly affair. Angry delegates roiled the hall, Yippies promising revolution and anarchy (“L.S.D. in the water!”), disaffected student radicals hurled bricks at the police. It was the Pentagon crowd aroused this time by violence and nihilism.

Part of the ill temper was produced by the death of Bobby Kennedy only two and a half months earlier. Kennedy would almost certainly have bested Humphrey to the nomination and, if beating Nixon, would likely have turned the country against the war. A film about him is shown to the delegates, and Mailer notes:

As the film progressed, and one saw scene after scene of Bobby Kennedy

growing older, a kind of happiness came back from the image, for

something in his face grew young over the years—he looked more like a

boy on the day of his death, a nice boy, nicer than the kid with the

sharp rocky glint in his eye who had gone to work for Joe McCarthy in

his early twenties . . . . He had grown modest as he grew older, and his wit

had grown with him—he had become a funny man, as the picture took care

to show, wry, simple for one instant, shy and off to the side on the

next, but with a sort of marvelous boy’s wisdom, as if he knew the

world was very bad and knew the intimate style of how it was bad, as

only boys can sometimes know . . . . Yet he had confidence that he was going

to fix it.

The maturation of Bobby Kennedy filled in, so to speak, the aloof indeterminacy that Mailer had noticed in his brother Jack eight years earlier. Even in his absence, Kennedy provided an emotional lift to the antiwar delegates that Eugene McCarthy could not provide. Eugene McCarthy! His student followers adored him. Demonstrating great courage in taking on L.B.J., he had declared his candidacy the previous December; he was one of the factors causing the President to drop out, and, after Kennedy’s death, he was the only one who could have stopped Humphrey. But McCarthy seemed fatally indifferent to the task. Mailer recalled his manner at a fund-raiser in Cambridge:

The crowd at the party, with their interminable questions and advice,

their over-familiarity yet excessive reverence, their desire to touch

McCarthy, prod him, galvanize him, seemed to do no more than

drive him deeper into insulations of his fatigue, his very

disenchantment—so his pores seemed to speak—with the democratic

process. He was not a mixer.

McCarthy was maddening. In public, he was diffident, unemphatic, he would not play the game; he wouldn’t even make a rousing speech for his supporters. Mailer visits him at the convention and realizes, however, that he is a not weak at all—on the contrary, he’s extremely tough, fatally tough, a man more intent on holding to his style than on saving the nation in crisis. Even at the time, his temperamental mildness seemed tragic, and something he said at the convention—“We’re not asking for much, just a modest use of intelligence”—is now positively heartbreaking. A modest use of intelligence! The sentiment seems utopian. Even Mailer couldn’t have known how thoroughly intelligence would be destroyed by power in the Trump era.

Against the mildness of McCarthy, there was the vicious power of the Chicago machine controlled by Mayor Richard Daley. The mayor was determined not to have his city, his convention, dominated by Jewish and Wasp media élites from the coasts, by Commies and hippies with their long hair and free sex and foul mouths. Politics is property, as Mailer says, and Daley’s property was enforced by the police on the street and his own goon squad in the hall:

Some of them had eyes like drills; others, noses like plows; jaws like

amputated knees . . . . No small matter to have the Illinois delegation

under your nose at the podium, all those hecklers, fixers, flunkies,

and musclemen scanning the audience as if to freeze certain

obstreperous faces . . . . The guys with eyes like drills always acted this

way, it was their purchase on stagecraft, but the difference in this

convention were the riots outside, and the roughing of the delegates

in the hall, the generator trucks on the perimeter of the stockyards,

ready to send voltage down the line of barbed wire, the police and

Canine Corps in the marches west of the Amphitheatre.

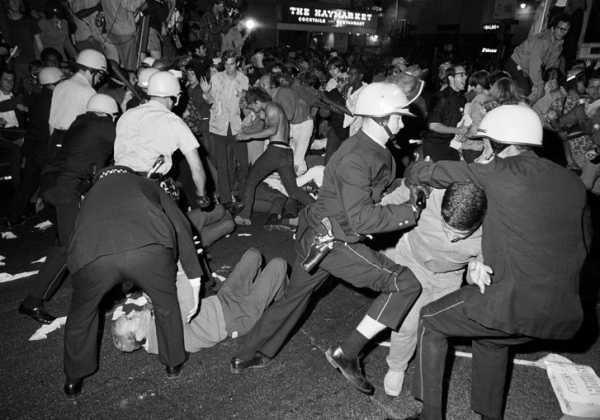

Fist fights break out in the hall between pro-war and antiwar partisans, Dan Rather and other media figures get roughed up, while Daley’s forces in the street use barbed wire, clubs, and tear gas to quell the demonstrators, some of whom were provocative and taunting (“Dump the Hump!”), others no more than indignant.

Police attack protesters outside of the Hilton.

Photograph from Bettmann / Getty

On the night of August 28th, in front of the Hilton Hotel, the Democratic headquarters, the police assaulted demonstrators, including passersby and people merely staying at the hotel. But in all this, Mailer is a witness, not a participant. He ducks the messy demonstrations for all sorts of reasons, the most salient of which is that he’s not going to write forty thousand words for Harper’s in the next few weeks if he gets clubbed on the head. But he also wonders if he isn’t simply “yellow”—too old and too established to fight. He loathes what’s happening during this war but he doesn’t, he admits, loathe his country, which has rewarded him well. He’s forty-five and he has two houses, six children, and a complicated set of obligations to collaborators of all sorts. He’s no revolutionary.

He stays inside the Hilton, and observes what he can—a lesson in making the most of a specialized perspective. The Hilton, under siege, is coming apart.

The Hilton heaved and staggered through a variety of attacks and

breakdowns. Like an old fort, like the old fort of the Democratic

Party, about to fall forever beneath the ministrations of its high

shaman, its excruciated warlock, derided by the young, held in

contempt by its own soldiers—the very delegates who would be loyal to

Humphrey in the nomination and loyal to nothing in their heart—this

spiritual fort of the Democratic Party was now housed in the

literal fort of the Hilton staggering in place, its boilers working,

all motors vibrating, yet seeming to come apart from the pressure on

the street outside . . . .

The laundry, the elevators, the telephones—nothing in the hotel works well and, in a further indignity, the tear gas unleashed by the police drifts into the air-conditioning system, where it joins the odor of stink bombs thrown by protesters. “Delegates, powerful political figures, old friends, and strangers all smelled awful,” he writes.

Talk about the backwash of the event! This is tragicomedy at a Shakespearean level. The appallingly violated Hilton and its denizens are not only a metaphor for the Democratic Party, they are a metaphor for the nation in a time of war, assassination, riot, and betrayal. Daley turns the police loose. “The police attacked . . . like a chain saw cutting into wood, the teeth of the saw the edge of their clubs, they attacked like a scythe through grass, lines of twenty and thirty policemen striking out in an arc, their clubs beating, demonstrators fleeing,” he writes. A later investigatory commission termed the excessive violence “a police riot.” At the time, people said, “It’s Vietnam, right here on Michigan Avenue.”

Mailer, with student activists, in Chicago’s Grant Park.

Photograph from Keystone Pictures / Alamy

The day before, Mailer had spoken to a bedraggled group of demonstrators. He was apologetic and even chagrined. He had finked, not been with them, and he would not, as we have seen, be with them that night in front of the Hilton. But the crowd cheered him anyway, and, at the end, several people shouted, “Write good, baby!” No kinder sentiment has ever been publically hurled at a writer. “Miami and the Siege of Chicago” is a companion volume to “Armies of the Night”—not as extensive, as grand, but in no way inferior in descriptive and rhetorical power.

Mailer is much out of fashion now, though the Library of America, reissuing his work, is doing its best to keep him alive. Surely his prescience about many things is startling. Consider: at the Republican convention in Miami, Mailer experiences a moment of irritation. He and the other reporters were kept waiting by the Reverend Ralph Abernathy, a disciple of Martin Luther King, Jr.,:

The reporter became aware after a while of a curious emotion in

himself, for he had not ever felt it consciously before—it was a

simple emotion and very unpleasant to him—he was getting tired of

Negroes and their rights. It was a miserable recognition, and on many

a count, for if he felt even a hint this way, then what

immeasurable tides of rage must be loose in America itself?

This modest bit of candor would be of zero significance to us were it not for what follows on the next page. Blacks, Mailer writes, were trying to make whites guilty. But how guilty?

Since obsessions dragoon our energy by endless repetitive

contemplations of guilt we can neither measure nor forget, political

power of the most frightening sort was obviously waiting for the first

demagogue who would smash the obsession and free the white man of his

guilt. Torrents of energy would be loosed, yes, those same torrents

which Hitler had freed in the Germans when he exploded their ten-year

obsession with whether they had lost the war through betrayal or

through material weakness. Through betrayal, Hitler had told them.

This premonition of Donald Trump and of what Trump has “loosed” in his audience was written exactly fifty years ago. At the moment, not one word of it seems excessive. “Miami & the Siege of Chicago” was composed at the worst time in our national life, though the current moment is a close second. Reading it gives not only pleasure of a literary sort but strength and solace. If the country could survive 1968, it will survive Donald Trump, too.

Sourse: newyorker.com