Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Pickles are a dollar each. Sugar-free cough drops go for a nickel. The sub special with three meats and two kinds of cheese is just $5.50. Only the newborn doesn’t have a price tag—serenely asleep, swaddled in a hospital blanket, she’s posed by the cash register of the Amish market. On a counter of faded disarray, a time capsule of both hues and prices, the baby alone looks new. But, as it turns out, not only is she not for sale, she’s not even real. The cashier, hardly visible except for her hand and apron, collects dolls and happened to have this startlingly realistic one with her the day that photographer Adali Schell came calling.

The baby doll is one of the many secrets in Schell’s extraordinary “New Paris” series. Some of those secrets are comic, others tragic, but all are absorbing. For starters, Schell’s Paris is more faux than nouveau: all these funny, fragile pictures were taken in and around an Ohio village on the Indiana state line named not for the French capital but for Paris, Kentucky, from which the village’s first residents migrated in the early nineteenth century. Schell, who is twenty-three, was born and raised and is still based in Los Angeles, but his mother is from the Buckeye state, and he grew up spending some of every summer there. Six years ago, when his grandmother died and his parents divorced, his mother left California and moved home for good, so he now spends even more time visiting.

When I spoke to Schell recently, he explained how divorce and death were the two great catalysts for “New Paris.” We talked just after he’d finished a shoot with the singer Amy Allen for the Times, an encore of sorts after photographing the comedian Conan O’Brien and the actor Austin Butler a few weeks before—the kind of assignments he’d dreamed of as a kid. “If you’d asked me at twelve,” he told me, “I would’ve said I just wanted to be a photographer for a newspaper or magazine.” That wasn’t long after he first got an iPod Touch and discovered that it had a camera. He carried it everywhere, documenting strangers, spending hours every day perfecting the art of street photography on Hollywood Boulevard, and then, when “he ran out of strangers,” moving on to friends and family. “I was a nervous, anxious kid growing up,” Schell said, “but taking pictures is a socially acceptable compulsion, so I’d just click, click, click.” The camera became “a kind of coping mechanism,” a safe way of interacting with the world.

Eventually, though, Schell began to think about the photographs only he could take, and since 2020, outside of commissions, he’s focussed his work on friends and family in Ohio. “No one’s making pictures of my mom responding to her divorce and working two jobs and raising my adopted sister on her own,” he told me. “No one’s making pictures of my grandfather smoking in his chair or visiting my grandmother’s grave.” Schell knows that the familial crises he has spent the past few years documenting are tragically ordinary—separation, sickness, grief, financial precarity—but some of his favorite photographers, from Richard Billingham in “Ray’s a Laugh” to Nan Goldin in “The Ballad of Sexual Dependency,” found similar inspiration in chaos close to home.

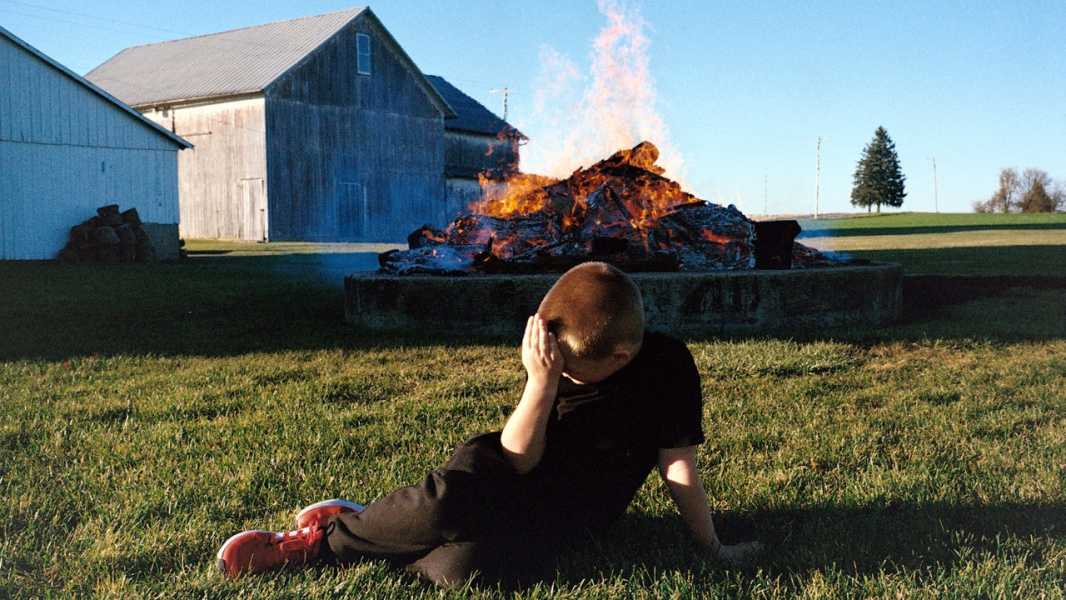

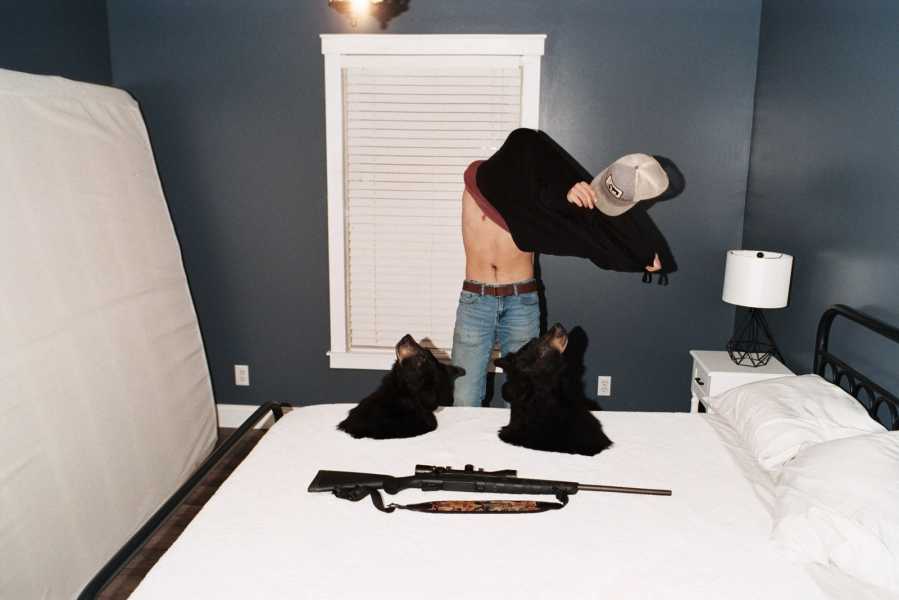

Like those iconic works, “New Paris” conjures a small society all its own. It is a world of mothers, sisters, grandfathers, cousins, and neighbors looking at us, away from us, and through us, framed by the windows, doors, picture frames, and computer screens that mediate everyday life. We watch as Schell’s cast of characters burn their trash, carpet their rooms, clean their guns, watch their televisions, walk their dogs, lead their horses, run their errands, and go about their busy days. Schell does not stage their portraits or engineer tableaux; he just captures the blur of dizzy motion as children play, the chaos of a chicken hurriedly flapping its wings, the hilarious shuffle as a seemingly headless man changes his shirt in front of two taxidermy bear heads, and—not dissimilarly—the exact instant in which a man reclining on the floor appears, chimera-like, with a dog’s head transposed on his own.

Although Schell is a digital native, he now shoots almost entirely on 35-mm. film, slowing down his practice. Instead of hundreds of attempts and outtakes, he watches and waits, trying to “honor the moment at hand.” Sometimes that makes his subjects appear as if they actively, willingly posed for him; other times, they seem wholly unaware of his camera. Often he makes use of a different kind of secrecy, photographing people who are concealed by puffs of smoke or blurs of light or smears of snow, obscurings that remind us of photography’s own limitations and the impossibility of capturing, much less conveying, the entirety of any person. Another artist might feel compelled to render death, divorce, and depression through sorrowful or saccharine poses, but “New Paris,” like the work of Larry Fink or Nick Waplington, is full of visual puns and comic confusions. A look of agony might really be a gasp of laughter; a man and his dog are touching in profile, but cheeky when shot from below, the dog’s rear end parallel to and puckered like the man’s beer belly.

Schell’s deep knowledge of his subjects allows him to show us how each individual is more complicated than the worst thing happening to them. Take the muse of “New Paris,” who appears more than anyone else: Schell’s grandfather, Charles McNally. “He’s impossible and hilarious,” the photographer told me. “He calls me Kenny Kodak, but if I put down my camera and I’m not taking his photo, he’ll be a troll and ask why I’m not taking it. Then he hides his face or tells me to shove it.” McNally once dreamed of being a standup comedian, but, after serving in the Marine Corps in Twentynine Palms and Okinawa, he came home to the Midwest to work as a barber and in a wire factory. He was married to Schell’s grandmother for fifty-five years, and he’s been adrift since she died in 2018, still writing her love letters on white paper plates that he leaves around the house, telling his family every time he sees them that he wishes she were still here. “My grandfather’s a creature of habit,” Schell says. “He has these rituals he follows every day.”

Some of McNally’s rituals are legible in the pictures of him in “New Paris.” When Schell jokes that his grandfather has a healthy routine of waking up to smoke and drink at home and then waiting for the hour of the day when he can smoke and drink at the American Legion, we can see the geography of his addictions and distractions. But other rituals are more hidden. A striking landscape shows Schell’s grandmother’s headstone looking lonely and cold, covered in snow and framed by a fraying Christmas stocking. But however the grave looks in the image, the photographer knows his grandfather visits it every day.

For the first few years, Schell thought he was documenting other people’s grief. Earlier this year, though, his grandfather was diagnosed with Stage IV cancer, and Schell realized how much of the project was about his own grief—unrealized but as certain as the other name already carved beside his grandmother’s on her headstone, awaiting only a death date. Disease is its own kind of secret, of course, one our bodies can keep even from us, and Schell’s photographs humble us with all that we cannot see when we look at one another. Some of our most essential identities—son, brother, grandson—can be as invisible to outsiders as the losses we endure. Schell has such an eye for emotion, and a gift for rendering the complexity, even the absurdity, of inner life and emotional turmoil, most especially his own.

Schell told me he’s related to most but not all of the “New Paris” subjects, but he likes that it’s almost impossible for viewers to know who’s who—another kind of riddle in the relationship between the photographer and those being photographed. Still, he very much wants viewers to know that his grandfather is Charles and his mother is Angela and his sister is Genevieve. He’s always used photography to capture his life, and he hopes that “New Paris” preserves their lives, too. His grandfather’s diagnosis brought even more urgency to his work, but when I asked if he was done photographing this part of the world, he said, “I wouldn’t be surprised if I shoot in New Paris forever.”

Sourse: newyorker.com