In order to see “The Battle of Atlanta” more or less the way that it was meant to be seen, you must take a short escalator up to a platform that stands about a third as high as the panoramic painting itself, which is nearly fifty feet tall and is now housed in a specially constructed room at the Atlanta History Center. The landscape circles all the way around you, its sky receding out of sight, its foreground populated by mannequins of soldiers on a dirt floor below. The lights dim, and a short film, projected onto the painting, begins to describe the critical moment, at a quarter to five in the afternoon, on July 22, 1864, when the Union General John A. (Black Jack) Logan decisively pushed back advancing Confederate forces as they stormed across a rail line outside of Atlanta, helping to hasten the end of the Civil War.

Moving pictures did not exist in the eighteen-eighties, when “The Battle of Atlanta” was painted, over the course of five months, by seventeen beer-drinking German artists employed by the American Panorama Company, in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Cycloramas were the cutting edge of history-as-entertainment. Many of these giant canvas paintings portrayed key moments from the Civil War: Gettysburg, for instance, or the Battle Above the Clouds. (A Gettysburg cyclorama is still displayed at a museum near the site of the battle.) “The Battle of Atlanta” was meant to depict a moment of glory for the North. The German artists consulted with Civil War veterans, striving for accuracy in the details of uniforms and locations, many of which they visited. When the painting was unveiled, in Minneapolis, in 1886, William Tecumseh Sherman declared it to be “the best picture of a battle on exhibition in this country.” Two years later, supporters of Benjamin Harrison, the Republican nominee for President, got him added to the painting before the cyclorama was displayed in his home state of Indiana. Harrison did not fight in the Battle of Atlanta—though he did fight nearby—and the cyclorama manager who’d allowed the repainting later resigned. (Harrison lost the popular vote but won the election; he was removed from the canvas more than a century later.)

In 1890, the painting was sold to a circus hustler named Paul Atkinson, who moved it to Chattanooga and altered its details so that it would appeal to Southern audiences: Confederate prisoners of war and a captured Confederate flag became Union P.O.W.s and a captured Union flag. Atkinson marketed the cyclorama as “the only Confederate victory ever painted.” It was not the revisionist cash cow that he hoped it would be, though. According to a recent piece, by Jack Hitt, in Smithsonian Magazine, Atkinson sold it, in 1893, for nine hundred and thirty-seven dollars, to the businessman Ernest Woodruff, who would later lead a group of investors who bought the Coca-Cola Company. Woodruff then sold it to a lumber merchant named George Gress, who moved it to Atlanta’s Grant Park neighborhood, which was also home to the recently created Atlanta Zoo. In the nineteen-thirties, a newspaper illustrator named Wilbur Kurtz added a number of proudly waving Confederate flags and soldiers to the painting. Legend has it that when Clark Gable visited Atlanta for the premiere of “Gone with the Wind,” he told Kurtz that the only thing he didn’t love about the cyclorama was that he wasn’t in it. So one of the soldier mannequins was painted to look like him.

Interest in the cyclorama waned, but, in 1979, local officials pushed to have the painting moved to the site of Stone Mountain, a massive carving, twenty miles east of Atlanta, which depicts Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis, and Stonewall Jackson astride their horses—the Confederate-sympathizer’s answer to Mount Rushmore. Atlanta’s first African-American mayor, Maynard Jackson, noted that the cyclorama portrayed “a battle that helped free my ancestors” and vowed to keep it in the city. James Earl Jones recorded a new introduction to the painting, which was once again seen not as a Confederate monument but as a tribute to the right side of history.

MORE FROM

Culture Desk

Unearthing Black History at Green-Wood Cemetery

A Buddy Guy Soundtrack

The New R. & B. Is Here, Reflecting Confused Modern Love

A Restaging of “Lolita, My Love,” the Musical “Too Dark to Live”

What to Do in N.Y.C. This Weekend: Phoebe Waller-Bridge, Rennie Harris, and Rhode Island-Style Pizza

Mort Gerberg on Fifty Years of Cartooning

It was during this period that Gordon Jones, the military historian and curator at the Atlanta History Center, first saw the cyclorama. “It didn’t do a thing for me at the time,” he said on a recent afternoon, as he looked at the restored and relocated painting, shortly before its public unveiling, in late February. “It was just a curiosity kept over by the zoo.” The painting attracted far fewer visitors than a famous ape, Willie B., who, for years, lived nearby.

Jones began to think about the painting again when he was a graduate student at Emory. He wrote a paper comparing the cyclorama to Stone Mountain, in which he described Stone Mountain as “a cultural white elephant in the middle of a themeless theme park,” and the cyclorama as “a wonder in search of resonance.” His point, he told me, was that the painting “had lost any kind of historical relevance that it had ever had—that all it had become was a battle story, crass entertainment. And that there was a lot more that we could make out of this.”

Standing in the painting’s new home, Jones, a white man in his mid-fifties who wears metal-framed glasses and a bushy gray beard, reflected on the still-roiling debates concerning Confederate monuments in the South and elsewhere. “We’re not going to be able to address these divisive issues in our country unless we can discuss the past,” he said. “If you can’t talk honestly about the past, there’s no way you can take on the present.” He added, “This painting can’t talk by itself, but it’s a start. By resurrecting this artifact and looking at all these different ways that it’s been used and interpreted, we’ll make people think. Thinking is good.”

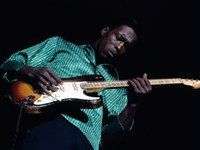

The painting depicts between three and six thousand people. Many of the faces, when you peer at them up close, are a little fuzzy.

Photograph by Jason and Natalie Hales / Atlanta History Center

Looking at the painting, as an Atlanta native, I recognized, in a general way, the rolling, tree-covered piedmont landscape and blood-stained red clay. I was struck, too, by the chaos—rather than falsely imposed order—of the battle scene, where men from both sides lay strewn about, as their comrades sought revenge, refuge, and deliverance using the rifled muskets and sabres of their day. Most of the thousands of faces in the painting were generic renditions of martial agony, ecstasy, or battlefield boredom. Jones once counted everyone in the painting; it depicts between three and six thousand people, depending on how you define individual figures. Among those thousands, there is just one African-American man, astride a horse. There are no women. Many of the faces, when you peer at them up close, are a little fuzzy. One of the exceptions is General Logan, a giant with a mane of dark hair. “Logan had star power,” Jones told me. “He’d draw an audience.” Indeed, the only recognizable figures in the original painting were Union officers known to Northern audiences: Logan, Sherman, a few others.

The painting had to be rolled up so that it could be lowered into its new, specially constructed room at the Atlanta History Center.

Photograph by Jason and Natalie Hales / Atlanta History Center

Moving the painting to its current location was an enormously expensive ordeal. After reading a story about the cyclorama in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, in 2013, a local real-estate entrepreneur named Lloyd Whitaker offered ten million dollars toward its preservation and transportation to a more fitting home; after that pledge, Sheffield Hale, the president and C.E.O. of the Atlanta History Center, raised another twenty-five million dollars in private contributions. A new, cathedral-like room was built; the painting’s fading blue skies were expanded, brightened, and angled slightly to create a hyperbolic shape heightening the illusion of battlefield reality. Three missing sections—cut out to accommodate smaller display locations over the years—were replaced, adding nearly three thousand square feet. More than a hundred three-dimensional diorama figures were restored in the foreground. The viewing platform was positioned in the middle of the room for visitors to take it all in.

The painting had to be rolled up so that it could be lowered into the newly constructed room, and Hale told me he had a recurring nightmare that it would all be for naught. “I thought when they unscrolled it, it would be blank,” he said. “Paint chips on the floor.” He shuddered. But the unrolled scrolls were not blank: they were full of detail, both historical and fabricated.

When I stood on the platform with Jones, before the unveiling, some schoolchildren were there. After the introductory film played, one of them, a black girl who told me that she was in the fourth grade, turned to Hale, who is, like Jones, a white man in his fifties, and who stood nearby. “My favorite part was all the history from what happened years ago,” she said. She added, “There was a lot happening back then.”

Sourse: newyorker.com