Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Early in 1947, the Swiss-born photographer Robert Frank boarded a liberty ship in Antwerp, Belgium; almost a month later, he arrived alone in New York, to make his way as an artist. There he met his first American friend, a fellow-photographer, Louis Faurer. The two men regularly convened at night to traverse Manhattan with their cameras. Frank, who published his famous collection “The Americans” in 1958, and became one of the twentieth century’s most influential photographers, often praised Faurer for the way that he could see into and reveal people of the sort they encountered together.

Robert Frank making a portrait for Allen Ginsberg’s “Collected Poems,” 7 Bleecker Street, 1984.Photograph by Brian Graham

One person Faurer memorably captured, in 1947, was his friend Frank, fresh off the boat and out on the job, beginning to search his new country for photographs. In Faurer’s portrait, Frank is part of a crowd gathered to watch an unfolding off-camera event. As the pedestrians crane and peer, Frank stands with hands in the pockets of his weathered pinstriped suit, quietly taking them in. The picture conveys Frank’s uncanny skill at blending with his surroundings, a form of tradecraft that enabled him to photograph strangers up close, unposed and uninhibited. Faurer’s subtle composition places Frank in line with the other figures, yet also offers him richer focus, setting him apart as someone of intrigue. He exudes potential energy, primed as a piston to point and click. It’s as though Faurer had been waiting for just the right chance to capture his friend as he already knew him to be.

Photograph by Brian Graham

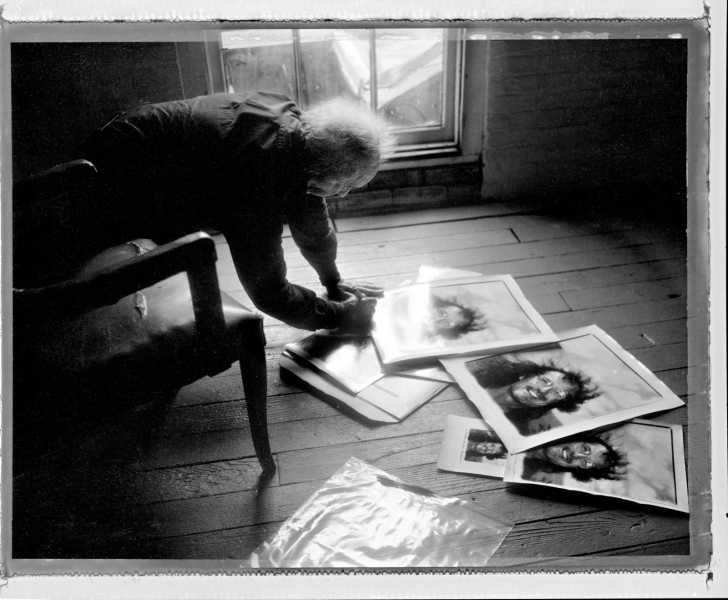

Robert Frank in Brian Graham’s darkroom at 101 Crosby Street, New York, 1987.Photograph by Brian Graham

So many other photographers would go on to photograph Frank that such portraits became a near-rite of professional passage. In 1952, Elliott Erwitt caught Frank dancing in a Spanish kitchen with his first wife, Mary, and flexing in his underwear while wading off the Valencia coast. Walker Evans made many Frank images, including one with Frank behind the wheel of a parked Buick Roadmaster, and another in which he sits at a rustic wooden table. Richard Avedon’s renditions of Frank glowering back at him, from 1975, imply what was true—that Frank considered Avedon a celebrity chaser, not an artist. (After the notably kempt Avedon’s session with the invariably uncombed Frank, Avedon made his most dishevelled self-portraits, as his biographer Philip Gefter observed.) Frank’s uncompromising ways intimidated many people, but, across the next seventy years, a number of younger photographers—including Danny Lyon, Danny Seymour, Jim Goldberg, Michal Rovner, Ed Grazda, Mellon Tytell, Ayumi Furuta (A-CHAN), and Chad Tobin—felt close to him, and (successfully) asked to take his picture.

Mabou, Cape Breton, 1979.Photograph by Brian Graham

Part of Frank’s willingness to submit was likely noblesse oblige; during his Zurich boyhood, he’d slept under a portrait of Franklin Roosevelt, and he preferred to photograph those he referred to as “outsiders,” especially “held back” women and men of all races and backgrounds. Frank’s private spirit was, like his chosen art form, essentially democratic. He enjoyed helping people. But the mercurial psychology running through him was as complex as the emotions he found in the faces of those he photographed himself. “Sometimes he’d forbid it and say No!” Gerhard Steidl, who publishes Frank, recalled recently. “But, other times, he’d become an actor in front of the camera.”

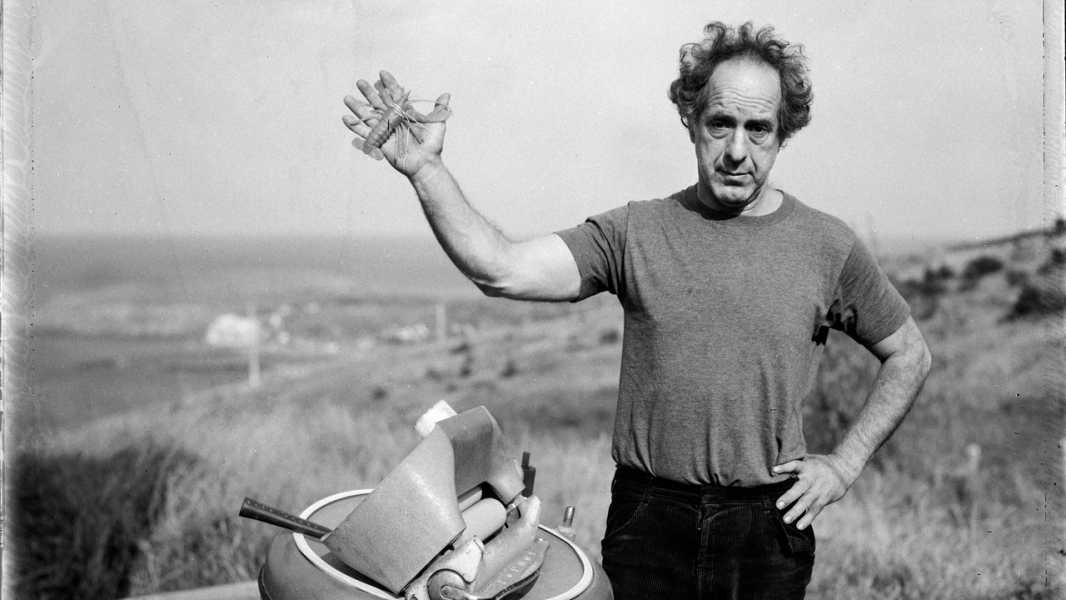

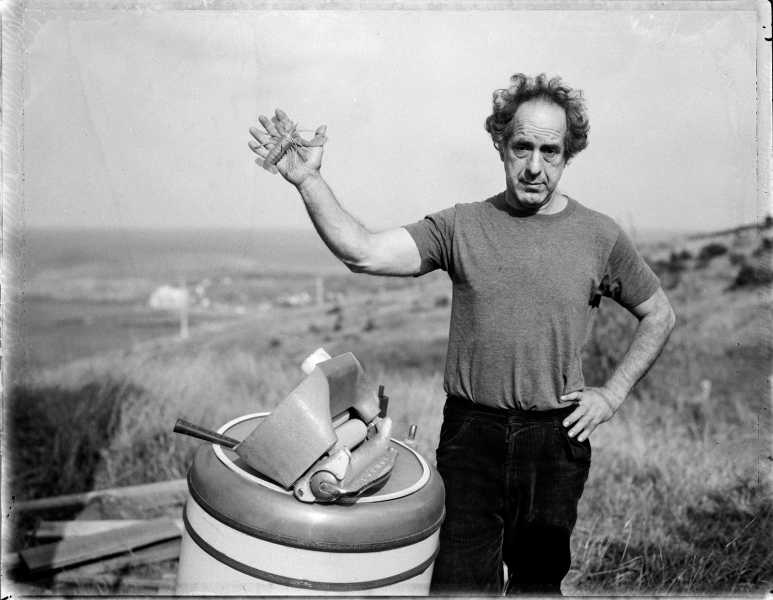

The photographer to whom Frank was most magnanimous was Brian Graham. Graham’s new book, “Goin’ Down the Road with Robert Frank,” also published by Steidl, documents the forty years he knew the man he called the Chief, from 1979 until Frank’s death, in 2019. In the nineteen-seventies, Frank had retreated from fame by living much of the time in a ramshackle cliff-top farmhouse on the remote island of Cape Breton, in northeastern Nova Scotia. Graham was from Glace Bay, a rough Cape Breton town of closed mines and struggling fisheries. His father was the mechanic at a bowling alley; Graham worked on off-shore and Alberta oil rigs, and taught school. He learned that “an important photographer” lived on Cape Breton; he’d begun taking photographs of Glace Bay, and decided to show him his photographs.

Raoul Hague’s cabin, Maverick Road, Woodstock, New York, 1988.Photograph by Brian Graham

The two became friendly. Later, Graham received a postcard from New York inviting him down to the big city: Frank had kept a space in a flophouse on Bleecker Street, and, eventually, he and his second wife, the artist June Leaf, bought it. Graham drove south in an old truck, and ended up staying on at Bleecker Street for years, helping Frank renovate the building, processing and printing Frank’s work, and looking after the property when Frank was away. “You couldn’t help but like Brian Graham,” Leaf told me. “Real Cape Breton. Kind of shy.” Graham said, “Maybe he liked me because I am the real Cape Breton.” Still, Frank’s patience with him had a limit, Graham said. “Robert hated it when I took a self-portrait of us. I’d crossed the line. His revenge was to scratch on the negative.”

Photograph by Robert Frank

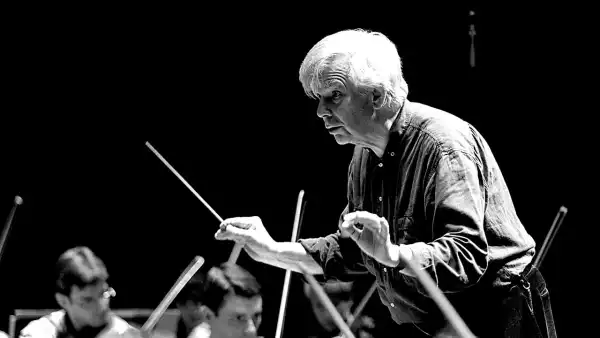

Another person who took Frank pictures, in the nineteen-sixties, was Tod Papageorge, who is not only an excellent photographer but among the finest writers on the form. I went to see him the other day to show him Graham’s book. “The Americans” meant a great deal to Papageorge, and he was curious about what Graham had seen during those decades of observing Frank. He opened Graham’s collection and took in the unfolding moments of a photographer’s life: Frank, stoic on the set of Rudy Wurlitzer’s and his film “Candy Mountain,” and Frank with a stay-off-my-land look in his eye while hammering patches into the Bleecker roof; Frank cavorting with Leaf, and Frank keeping busy among such friends as Wurlitzer, Allen Ginsberg, Jim Jarmusch, Harry Smith, and Tom Waits. “He’s definitely responding to Graham differently,” Papageorge said, looking at the portraits. “He’s more relaxed. And when he isn’t completely relaxed, you feel him trying to be the person young Brian knows. He’s almost struggling to be himself, but he’s doing a pretty good job of it.”

Roof repair, 7 Bleecker Street, 1981.Photograph by Brian Graham

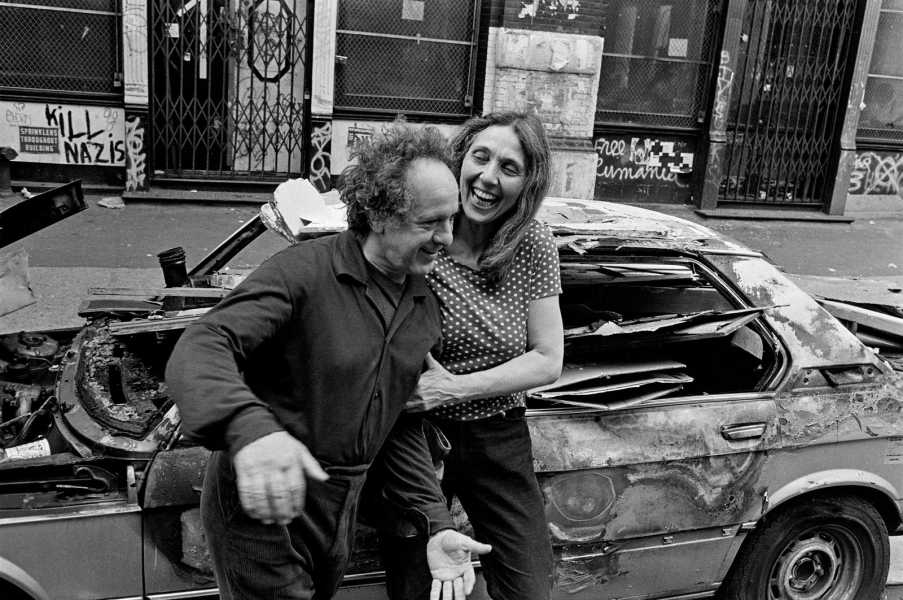

Robert Frank and June Leaf on Bleecker Street, 1982.Photograph by Brian Graham

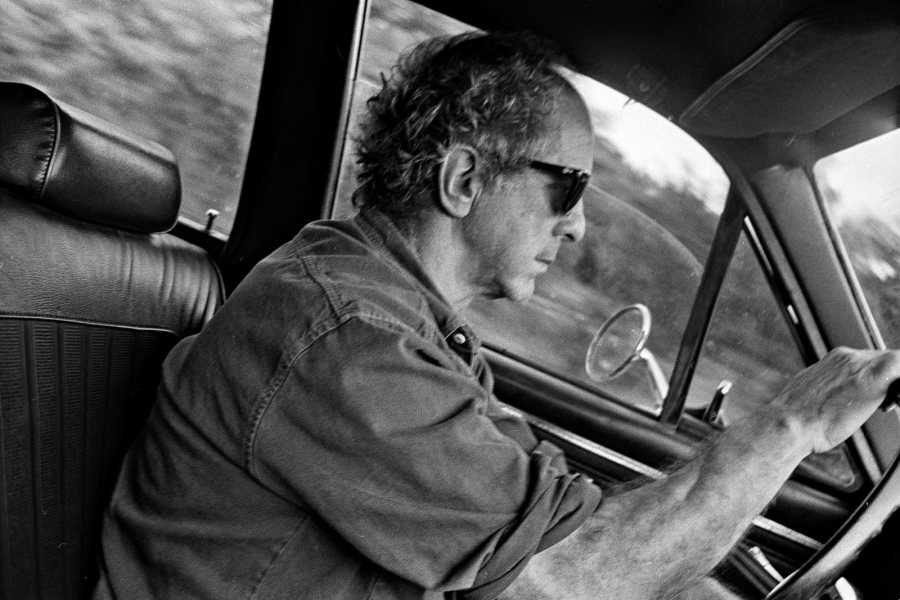

Papageorge considered the most successful picture in Graham’s book to be one of Frank visiting a mentor, the irascible sculptor Raoul Hague, who lived in a cabin in Woodstock. The photograph, taken from outside, shows Frank and Hague seated, facing each other, inside the cabin, framed by separate windows, with an empty window between them. “There’s an idea here,” Papageorge said, “each person existing in a separate cabin of self.” The picture also seemed to gesture to a famous image from “The Americans,” a front-to-back line of white-then-Black faces looking out from a segregated New Orleans streetcar. Frank drove well over ten thousand miles while making “The Americans,” and a picture by Graham, from 1992, of Frank vehemently commanding a Ford Falcon station wagon, made Papageorge say, “You know this guy’s gonna get you there.” It reminded Papageorge of another photo from “The Americans,” of hitchhikers whom Frank picked up in Blackfoot, Idaho. One hitchhiker spelled Frank at the wheel, and, from the back seat, Frank surreptitiously got his picture.

Graham’s pictures inevitably invite comparison, and contrast, with Frank’s—as a recent exhibit, at the Inverness County Centre for the Arts, on Cape Breton, made explicit, displaying the “Goin’ Down the Road” images alongside those from Frank’s last collection, “Good days Quiet,” which is mainly a meditation on Frank’s life in Cape Breton. (Most of the pictures were taken in the seventies and eighties and were never printed until Frank put the book together, toward the end of his life.) Frank was a literary photographer in the sense that his pictures possess narrative and character, hold the emotional resonance of short stories. “Lived experience and vivaciousness,” Papageorge noted of one picture, “real echoes of art history and Virginia Woolf.”

Pablo Frank and his girlfriend Rhonda.Photograph by Robert Frank

Papageorge got out “Good days Quiet,” and flipped to a stunning Cape Breton winter land-and-sea expanse, with footprints in the snow. Frank could locate emotion pretty well anywhere, Papageorge said. “I remember Robert came to Yale once,” he went on. “He got out of the taxi, he looks down at the pavement, and got totally engrossed in the impression a few leaves had left in the concrete.” He added, “With Robert, it’s interesting how still the pictures are even as they express motion. His gift is offering a sense of things about to move, about to happen.”

Then Papageorge was smiling, at a portrait of Frank’s son, Pablo, with his girlfriend, both happy and tender with youth. After Frank’s daughter, Andrea, was killed in an airplane crash at twenty, Pablo descended into mental illness, and eventually died by suicide. Papageorge, too, had photographed Pablo, as a teen-ager, and here he was moved by how sure of each other the two young people had looked. “Not many people can photograph their kid and you’d want it on your wall,” he said. “Robert said of Walker Evans that Evans thought he was superior to other people. He’s probably right, but it’s still unfair. Some people are superior. Evans was superior. Robert was, too.” ♦

Signing prints, Newark, New Jersey, 2002.Photograph by Brian Graham

Sourse: newyorker.com