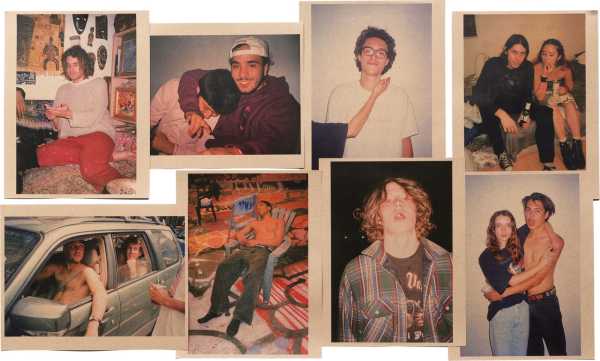

Two varieties of nostalgia merge in Adam Zhu’s photo book “Nice Daze.” The imagery, shot between 2013 and 2020, beginning when the artist was just sixteen, forms something like a yearbook, though not one associated with any institution. An impressionistic chronicle of the recent past, it follows Zhu’s friends and his friends’ friends—a multigenerational group of skateboarders, graffiti writers, artists, musicians, and attendees of crowded parties—around New York’s East Village, Lower East Side, and Chinatown.

“Wiki and Destiny in the deli.”

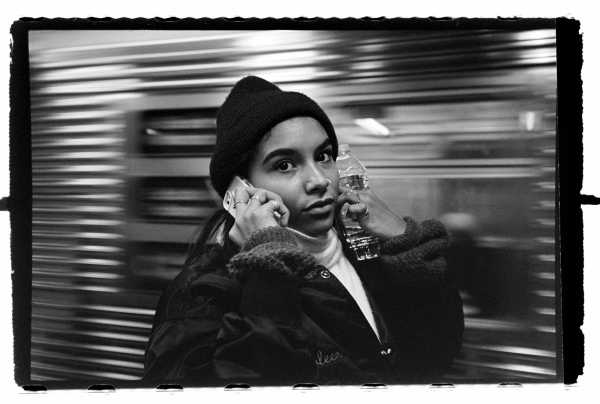

Mostly, it tells a happy story, of people glad to see the kid behind the point-and-shoot. Zhu shows us, in the book’s comment-less, uncaptioned procession of photos, such scenes as five bathers in an inflated kiddie pool on a rooftop, looking up at him, wherever he’s perched; girls striking poses on a crowded D train; an early-career Princess Nokia, with a toothy smile, standing in the aisle of a bodega with a friend while holding crumpled bills in front of vacuum-packed bricks of Cuban-style coffee; and, in a twelve-image grid, a sunlit view of a young man assiduously rolling a blunt, step by step. But, as with anything, really, where youth is so foregrounded, there’s an ever-present note of bittersweetness. As you look at Zhu’s depictions of amorphous and pack-like social configurations, fleeting experiments in style and thrill-seeking, and elevated forms of doing nothing, you feel the clock quietly ticking down to adulthood.

“Sam, Milah, Olivia, Ally Bo, and Arvid at Romeo.”

“Wiki rolling a blunt.”

“Isabel.”

Zhu’s portrait of overlapping subcultures feels wistful for a more remote era, too. In his version of the city, which is notably shot on film, there are no Starbucks or Sweetgreen, no luxury-condo developments, no obvious signs of hyper-gentrification. Here and there you spot an iPhone, but many of the photos, at first glance, could date from decades ago—from the nineteen-eighties, perhaps, when movements and communities took root in grittier downtown terrain, and the ferment included hip-hop, New Wave, No Wave, and the East Village gallery scene. One of the book’s most beautiful two-page spreads features members of the experimental-jazz group Onyx Collective. In the diptych, a saxophonist (holding two of the instruments, one in each hand) and a drummer play in a cavernous space, whose walls and cement floor are covered with graffiti. The performers wear masks cobbled together from what looks like blue repurposed fabric; one wears a punctured paper plate over his face. Against the spray-painted backdrop, their upcycled attire gestures to the work of the artist-rapper-philosopher Rammellzee—his “Garbage Gods” series, initiated in the mid-eighties, was composed of visionary found-object sculptures that could be worn like armor.

“Onyx Collective.”

“Kunle, IRAK.”

Rammellzee, who died in 2010, at the age of forty-nine, is name-checked in an introductory essay to “Nice Daze,” written by Dumar Novyo (also known as Dumar Brown or Nov York), an author and graffiti artist who emerged in the nineties. “We need Rammellzee today more than ever,” Novyo writes, mourning a bygone underground, though he sees its tensions in the not-so-different scene of today. “DIY is still en vogue,” he continues, “& the neoliberal drive to co-opt youthful DIY style & commodify it is still en vogue.”

“Onyx Collective’s first jam in the shed.”

Zhu isn’t naïve to the dynamics of commodification—the marketing of street style or youth culture. (Nor was Rammellzee, who became the first artist to collaborate with the brand Supreme). Zhu is also a creative director, represented by the agency Camera Club, and his work captures the contours of an expansive, hybrid creative community, one inextricable from the city’s—and the world’s—culture industries. As a result, “Nice Daze” reflects a precocious savvy and is peppered with boldface names such as Kembra Pfahler, Earl Sweatshirt, and Harmony Korine. In the back of the volume, though, they are listed only in order of appearance, and the images themselves are presented in varied, nonhierarchical ways—many in collage-like, teen-bedroom-style walls of snapshot-size prints—so that subjects’ identities are incidental unless you happen to know them, too.

“Thebe and Sage backstage.”

“POSHGOD, Sporting Life, and Wiki.”

Larry Clark’s raw explorations of subculture are, in some sense, a precursor to Zhu’s work. Aspects of Dash Snow’s punk materiality and diaristic depictions of art-world-adjacent abjection echo here, too. But the book is comparatively wholesome, free from nihilism, a highly personal record interested not in Gen Z particularities (the group’s bemoaned online-ness or novel transgressions) but in revisiting familiar coming-of-age themes, instead. Aptly titled, the book passes in a nice daze. As to its consequence as a historical document, it’s hard to say—the significance of even exceptional juvenilia hinges on what the artist does next. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com