In the early nineties, I worked briefly as an assistant editor at Aperture, a job that involved considering unsolicited submissions of photographs. It was my good fortune that one such set of submissions was delivered to the office by the photographer himself, Milton Rogovin, and his wife, Anne, a writer and teacher. They lived in Buffalo, Anne’s home town, where Milton, a Jewish New York City native, born in 1909, was once a practicing optometrist and had long been photographing residents of his adoptive city’s relatively poor neighborhoods. The Rogovins brought a batch of his recent photos, from Buffalo’s Lower West Side, near where he had an optometry practice; some of his earlier work had been published by Aperture, and I hoped the same would happen with these newer images. It didn’t happen, but a spate of books from other publishers nonetheless followed, starting in 1994, showcasing an extraordinary body of work and with it an extraordinary couple—Milton wielded the camera, but the life project that his images embodied was a joint venture of his and Anne’s.

“Untitled (Grandfather and Granddaughter),” 1973.

“Untitled (Grandfather and Granddaughter),” 1984.

“Untitled (Grandfather and Granddaughter),” 1992.

A longtime Communist and an official with the Party in Buffalo, Milton faced persecution and was subpoenaed by the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1957. His political activism—at a time when the Communist Party made racial equality a prime issue, during an era of rampant discrimination—connected crucially with his artistic endeavors. He made photographs during trips with Anne to Mexico and to mining towns in Appalachia; Aperture published a series of his photographs taken in Black storefront churches in Buffalo in 1962, with an introduction by W. E. B. Du Bois. But it was in Buffalo’s ethnically diverse Lower West Side that his artistic methods reached their full flowering.

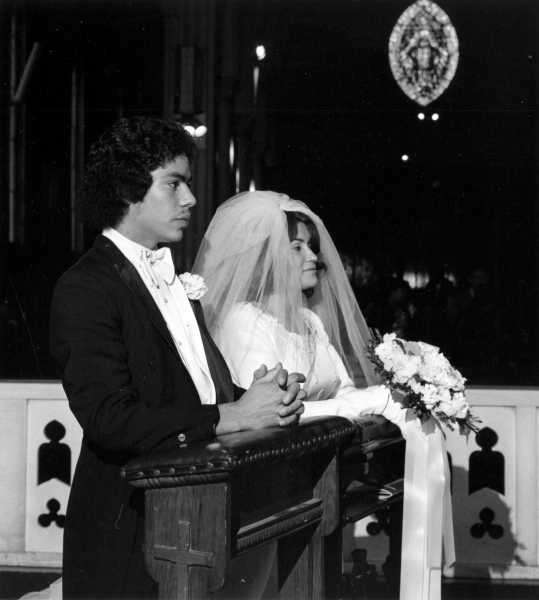

“Michael and Pam,” 1972.

“Michael and Pam,” 1984.

“Michael and Pam,” 1992.

“Michael and Pam,” 2002.

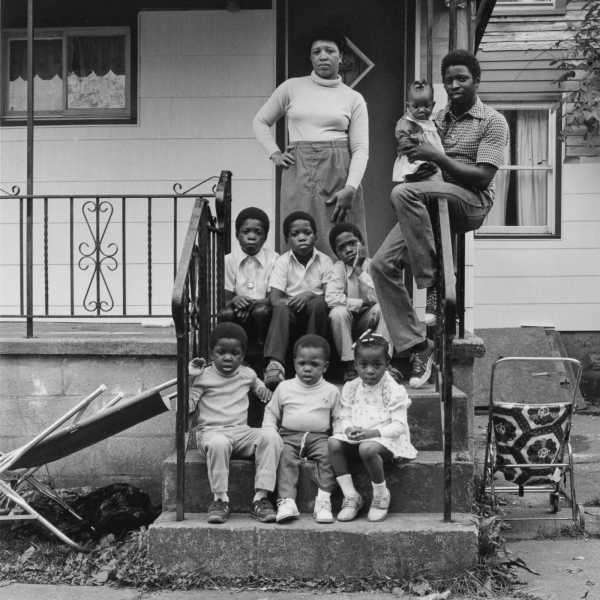

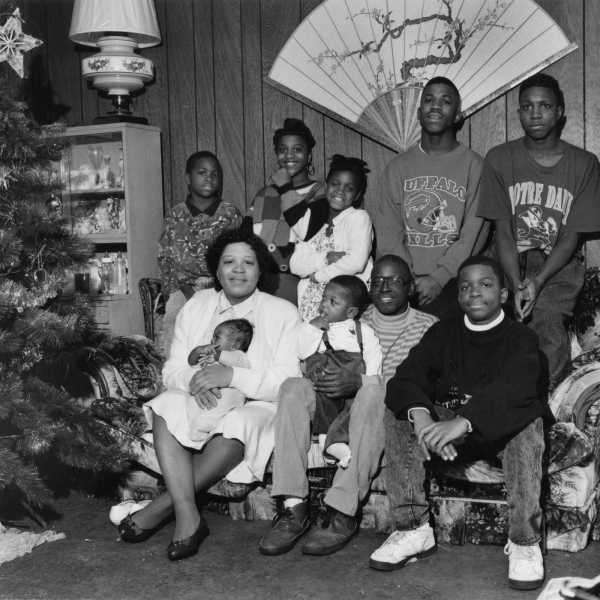

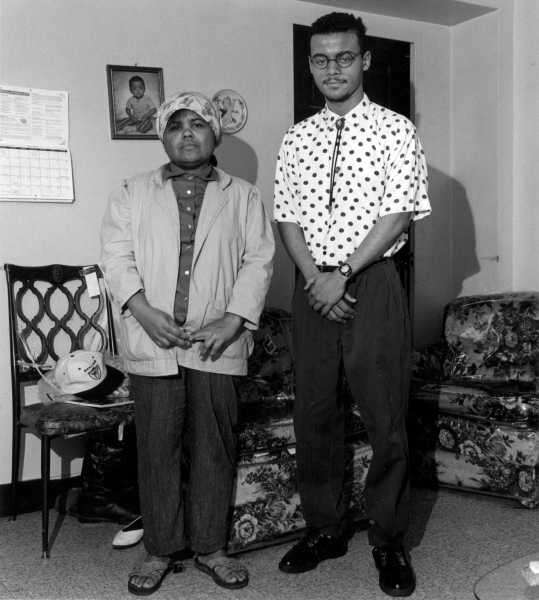

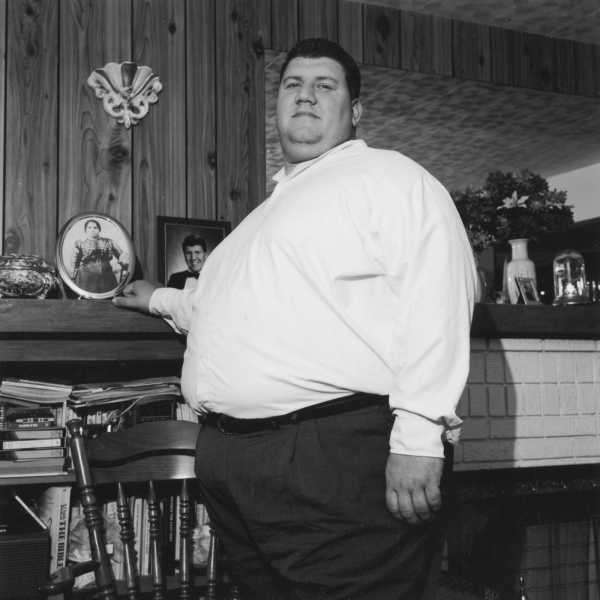

Milton’s photographs from the neighborhood originated in 1972, when he was invited to visit the home of a patient, and continued as he and Anne developed relationships with others they met. The elements of personal connection and social history, implicit in Milton’s earlier images, are rendered explicit in his series “Lower West Side Triptychs” and “Lower West Side Quartets.” For those projects, the Rogovins sought out people Milton had photographed in the nineteen-seventies and photographed them again during the course of three decades. The triptychs link the earlier images to ones from the Rogovins’ return visits to the neighborhood in the nineteen-eighties and nineties; the quartets feature an extra installment made in 2002, when Milton was ninety-two. (Anne died the following year; Milton died in 2011.) Each set is presented chronologically, in a row, revealing the changes in individual lives and family circumstances through the years, while also reaching deep into grand abstractions of nature and time—the cycle of life, with deaths and births, absences and arrivals, deterioration and maturation.

“Mother and Son,” 1974.

“Mother and Son,” 1985.

“Mother and Son,” 1992.

Milton’s photographs have a simplicity—a repetitive, even obsessional unity—that extends his photographic methods into an artistic philosophy that meshes with his social ideals. His distinctive style goes far beyond portraiture; he photographs his subjects in casual settings, often at home or outdoors, but with a plain formality that evokes a planned occasion rather than mere happenstance. Milton and his subjects face each other, in mutual awareness—and they do so from a distance that is itself as mark of his respect, in several regards. The distance implies an incommensurable gap in experience that the camera, and even personal acquaintance, can’t overcome.

“Grandparents and Baptism Boy,” 1974.

“Grandparents and Baptism Boy,” 1985.

“Grandparents and Baptism Boy,” 1992.

“Grandparents and Baptism Boy,” 2002.

At the same time, Milton doesn’t employ telephoto lenses to fabricate visual proximity. He presents his subjects in full-body shots, or nearly so, because, for all his attentive devotion to the expressive power of their faces, his images don’t presume to explore the mystical auras of inner lives. He displays a love of posture and gesture, clothing and décor. He thrills in the expressive power of self-presentation, whether bodily or material. The images show cramped living rooms and cracked pavement, bicycles and baby carriages, graffiti-covered walls and well-scrubbed front porches, in an exploration of circumstance that goes far beyond the reportorial. The style provides a window in time upon realities of all sorts—physical, emotional, material—which are presented with their full measure of inherent dignity. In these photographs, a T-shirt from a chain store has the same grace as a suit; a stance of modest reserve has the same gravitas as one of brazen pride. The formality of Milton’s photos captures the informalities of daily lives, while reflecting the grandeur of ordinary cares and yearnings.

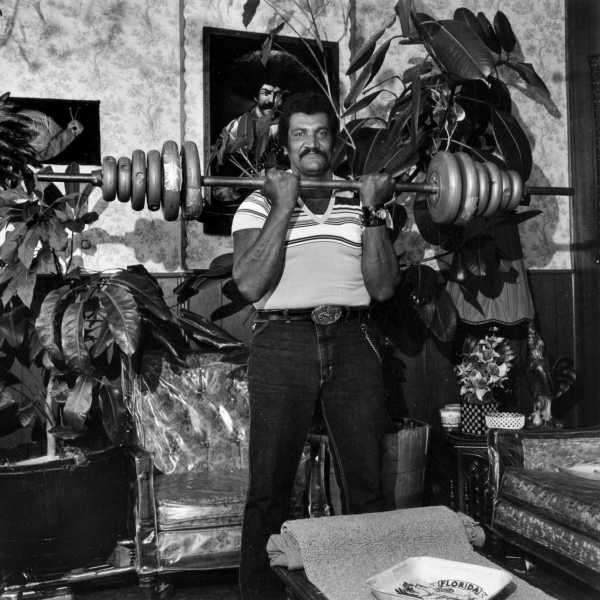

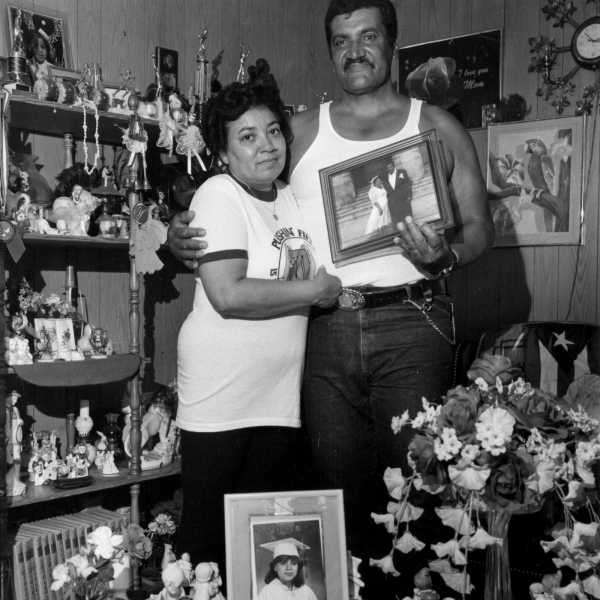

“Felix and wife,” 1973.

“Felix and wife,” 1984.

“Felix and wife,” 1992.

It’s a longstanding pet peeve of mine that the concept of cinéma vérité has largely come to signify the narrow method of filmmakers embedding themselves such that they are rendered seemingly invisible to subjects, who go about their business for the camera while forgetting, or not caring, that they’re being filmed. A similar idea extends to the practice of photography, with much of the art depending on so-called stolen moments—with all the exploitative one-sidedness that the term implies. Milton Rogovin’s images seem to me to provide a crucial model of creative ethics, for photographers and filmmakers alike. As with the founding impulse of cinéma vérité, they’re interactive; his work is transactional, reflecting both the mutual regard and the mutual respect of subjects and artists. In their blend of openness and reserve, personal devotion and respect for privacy, they present the power and the limits of images themselves—an honoring of the enormity of the intimate and cosmic mysteries that they embody. ♦

“Roy and Millie,” 1974.

“Roy and Millie,” 1985.

“Roy and Millie,” 1992.

“Roy and Millie,” 2002.

Sourse: newyorker.com