Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

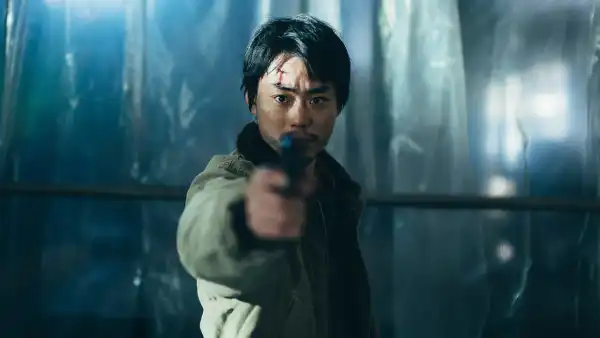

Ryosuke Yoshii (Masaki Suda), the thirty-year-old central character of the mesmerizing Japanese thriller Cloud, is happiest when he’s sitting in front of a computer. Some people would understand that, but Yoshii—slim, handsome, and aloof—is not your typical guy. In a dimly lit, small Tokyo apartment, he settles in close to the screen, studying rows of identical blinking icons, each representing a product for sale online. Within minutes, almost all of his inventory has sold out. Yet Yoshii, though hundreds of thousands of yen richer, barely smiles. It’s not the wealth itself that bothers him so much as the cool, competitive atmosphere of e-commerce: the cozy glow of the screen, the silence and privacy of the transactions, and the speed with which those icons change color and status—all blinking confirmations of a job well done.

Yoshii is an online salesman who buys goods in bulk and resells them at grossly inflated prices. The goods themselves—counterfeit designer handbags, limited-edition collectible dolls—are as unimportant to him as the suffering of those he defrauds. In the opening scene, Yoshii offers an elderly couple (Masaaki Akahori and Maho Yamada) thirty medical therapy devices for ninety thousand yen, or about six hundred US dollars, far less than he will ultimately charge for a single device. The salesmen protest, recognizing that they are being deceived but also realizing that they have no other choice. Yoshii ignores their anger and begins loading the devices into his truck. What is evident in these and other actions is not simply an indifference to emotion, but a clear impatience with it and a growing desire to eliminate extraneous human interactions entirely.

This includes dealing with people who until now considered themselves his friends and colleagues. The film’s opening scenes are tense variations on a cynical theme: a stone-faced Yoshii repeatedly ignores quiet, desperate pleas for help, mercy, or just basic respect. As his business prospers, Yoshii decides to quit his day job at a garment factory, to the shock and disappointment of his boss, Takimoto (Yoshiyoshi Arakawa), who has just offered him a promotion. Longtime friend Muraoka (Masataka Kubota), who introduced Yoshii to the business, tries unsuccessfully to persuade him to invest in the new venture. In each of these acrimonious, increasingly hostile encounters, it is not what Yoshii says but what he doesn’t say—about his intentions, his methods, his success—that earns the scorn and resentment of those around him.

Soon, Yoshii begins to receive ominous warnings—a dead rodent left outside his apartment, a tripwire strung across his motorcycle path, an intruder at his front door—and decides it’s time to leave Tokyo. He finds a house in a remote wooded area, spacious enough to serve as a base for his ever-expanding business. There’s also room for his girlfriend, Akiko (Kotone Furakawa), though her presence in the house and in his life is peripheral at best; Yoshii pays little more attention to her than he does to Sano (Daiken Okudaira), a newly hired young assistant who takes to the job with a touching, sometimes intrusive zeal. Yoshii tolerates the presence of others only as long as they don’t interfere with his work or add too much color to his new home, which, despite its picturesque views, has the feel of a particularly drab, impersonal office.

“The Cloud” is the latest effort from writer-director Kiyoshi Kurosawa, who has spent much of his four-decade-plus career intertwining genre conventions with the social and spiritual norms of modernity. Kurosawa is so prolific—he has exhaustively explored the boundaries of supernatural horror, apocalyptic science fiction, detective fiction, and other thrillers—that it makes the auteur’s usual game of pan-creative contrasts and comparisons especially difficult. Still, there are moments in “The Cloud” that, to my mind, echo Kurosawa’s “Pulse,” a deeply unsettling ghost story that came out in Japan in 2001. In it, the director, in a dark probe of the then-nascent arena of the Internet, poses a series of techno-philosophical riddles: What if our screens are portals to a crowded underworld of hell? What if the isolation of final online existence were a prelude to the “eternal loneliness” of death?

(Note: Pulse was released in American theaters in 2005, by Magnolia Pictures. Before that, it spent four years in limbo at Miramax Films, which, rather than release it, poured its resources into an English-language remake—an act of product acquisition, suppression, and watering down to make Yoshii's brokering scam seem fairly innocuous.)

Pulse was born on the last legs of the floppy disk era, and although its action

Sourse: newyorker.com