Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

With the very essence of government crumbling from within, the unusual documentary Drop Dead City focuses on the functions and responsibilities of government by reconstructing in detail New York City's financial crisis of the mid-1970s. By examining the causes of the crisis, its short-term effects, and the difficulties of resolving it, the film raises philosophical questions about the situation—the social ideals that led the city to financial collapse, and the political forces that nearly prevented its rescue.

The documentary’s title comes from one of the most famous episodes of the crisis: in October 1975, with the city on the brink of bankruptcy, President Gerald Ford announced his intention to veto any congressional bailout bill; the next day, the Daily News ran a headline that quickly became iconic: “FORD IN TOWN: DROP DEAD.” Its impact was significant: Ford became the target of protests in New York City, national polls on the bailout turned from negative to positive, and by the end of the year, he had signed a bill authorizing $2.3 billion in federal loans. Despite his retreat, Ford remained an antihero in the city’s popular narrative, and he was remembered. When he narrowly lost the 1976 election to President Jimmy Carter, New York carried the Electoral College and New York itself carried the state.

Drop Dead City is co-directed by Peter Yost and Michael Rohatyn. Yost, a veteran documentary filmmaker, has demonstrated his expertise in handling data; the film masterfully unpacks the complex history of financial nuance and political maneuvering, as well as social and personal backstories, with a deft touch and a lively sense of wonder. He makes deft use of archival footage—partial and selective, but resonant and compelling—to capture the atmosphere of the city at the time. Along with Yost, Rohatyn takes a subject that goes beyond the historical: his father, Felix Rohatyn, was an investment banker who orchestrated the city’s financial rescue. (Felix passed away in 2019, but appears frequently in the archival footage.) Michael is best known as a composer—he wrote the film’s score and can be heard playing keyboards and guitar—and Drop Dead City is clearly a personal project for him; he has mentioned filming 200 hours of footage. Although Michael was only twelve years old in 1975, the story is still part of his world, and the casual candor with which many of the drama's key players speak on camera is no doubt due to their closeness to him.

The story told in Drop Dead City remains compelling even after half a century. In 1974, New York City’s new mayor, Abraham Beame, took office believing the city was $2 billion in debt. He’d been the city’s comptroller for the previous four years, so you’d think he’d know. However, his young successor in the job, Harrison Goldin, conducted an audit and discovered the debt was actually about $6 billion. The financial situation was a mess; at one point, Goldin stumbled upon a huge stack of bad checks hidden in a filing cabinet. The problem wasn’t that the city’s books were wrong, it was that “there weren’t any damn books,” as Steven Berger, who was later brought in to help fix the situation as head of the newly created Emergency Financial Control Board, put it. The story took a New Emperor turn: The city paid its wages by issuing round after round of short-term bonds, underwritten by the banks. In early 1975, John Osnato, a young lawyer representing one of the banks involved, asked the assistant comptroller about the estimated tax revenues needed to back the bonds and, dissatisfied with the answers, found that they were inadequate. The banks promptly refused to underwrite the bonds.

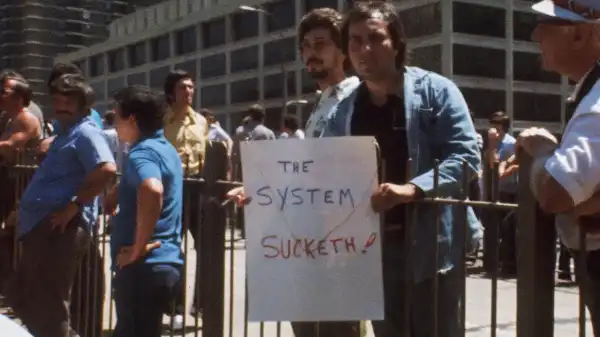

Beame cut spending by laying off city employees, including teachers, police officers, firefighters, and sanitation workers. This led to protests and strikes; trash piled up in the streets, drawbridges remained up, and police and fire unions tried to scare tourists away from the city by spreading rumors of a “City of Fear.” (Former Mayor David Dinkins calls this last maneuver “disgraceful.”) Beame, a longtime club politician, twisted arms: When one union offered to invest part of its pension fund in municipal bonds, some of its members were rehired. He also turned to New York state and its new governor, Hugh Carey, for help. Carey brought in Felix Rohatyn, a Wall Street veteran, to create the Municipal Assistance Corporation (MAC). Rohatyn was tasked with bringing together banks, unions, politicians, and bureaucrats to agree on a rescue plan.

Institutional creativity in crisis in Drop Dead City is almost aesthetically pleasing—and serves as an important reminder, if one were needed, that institutions embody ideals, just as the destruction of institutions also

Sourse: newyorker.com