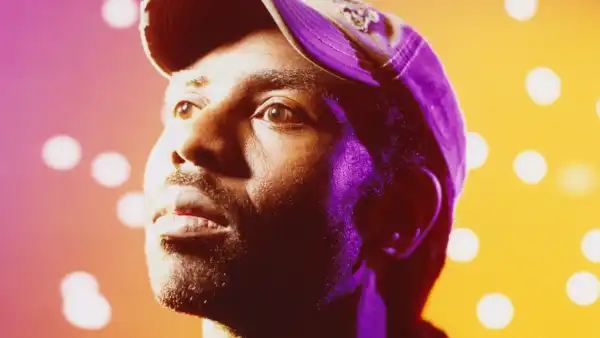

David Shaw is fifty years old. Last month, he stepped down as the head coach of Stanford’s football team, a position that he had held for twelve years. For four years before that, he had been the team’s offensive coördinator, under Jim Harbaugh. Shaw’s father, Willie, had been a coach at Stanford, and David had been a wide receiver there, in the nineteen-nineties; he was also on the basketball and track teams. David Shaw became the winningest coach in the history of Stanford, the longest-tenured Black coach at college football’s highest level, and the winningest Black coach in the history of the country’s top college-football conferences. On the sidelines, he was a quiet presence—“I’m a ‘measure twice, cut once’ person,” he told me—with a certain heft and poise. He had a stoic’s expression and a receiver’s hands.

Shaw and Harbaugh came to Stanford together, in 2007. The year before, the team had gone 1–11. Within a few years, and with the help of Andrew Luck at quarterback, Stanford became one of the best teams in the country, and remained one even after Harbaugh and then Luck left for the N.F.L. As head coach, Shaw went to the Rose Bowl three times in four years, winning twice. He won three Pac-12 titles. His teams were famous for their physical style, their imposing offensive and defensive lines, their bruising backfield. He called it “intellectual brutality.” But Stanford’s run of success didn’t last. Stanford’s defense, formerly one of the best in the country, became one of the worst, ranked outside the top hundred. Its rushing game, destroyed by injuries, was nonexistent. During the pandemic, the team had to play some of its home games out of state, in compliance with local COVID-19 rules. Exhausted, the players turned down an invitation to a bowl game.

2022 in Review

New Yorker writers reflect on the year’s highs and lows.

The pandemic was only one of the seismic disruptions in college football. The advent of “name, image, likeness” (N.I.L.) deals, which allow college athletes to earn compensation for endorsement deals or other uses of their name and notoriety, and of new rules facilitating the transfer process for N.C.A.A. athletes who wish to play at different schools—the so-called transfer portal—only made things more difficult for Stanford. Other teams changed their approaches and rebuilt teams through the portal on the fly. Stanford was slow to change, and Shaw was ever methodical.

Stanford went 3–9 two seasons in a row. There were calls to fire the coach, which probably would have been even louder if the program had been more relevant to the national rankings. In the end, Shaw made the decision to leave. He thought of his friends Chris Petersen, who stepped down as head coach of the University of Washington, at age fifty-five, despite a run of success, and Luck, one of the most talented quarterbacks the sport has ever seen, who shocked the football world when he retired from the N.F.L., in 2019, at the age of twenty-nine, citing the endless cycle of injuries and rehabilitation. Shaw had talked to Petersen and Luck after their announcements, and he had been struck by how much sense their respective decisions made to them, despite what everyone else thought. His decision felt the same. It made him feel at peace.

Stanford lost its last game of the season, 35–26, to B.Y.U. The stadium was half empty. Afterward, Shaw told his team, and then the media, that he wouldn’t be back. He told me that, a few days later, he sat down to dinner with his family. “No one was rushed,” he said. “That just doesn’t happen for football coaches. It was great.” He wasn’t retiring, but he wasn’t rushing to find a new coaching job, either. The college-football landscape was changing, and Stanford was going to have to change with it. It would be the start of a new era. “How can you have a guy who’s been there for twelve years be the beginning?” Shaw said.

This year, stadiums have been full again. Masks, for the most part, are off. Daily COVID tests are a thing of the past. A photograph of a regular-season N.B.A. game in the fall of 2022 would look similar to a picture of a game in the fall of 2019; it can appear as though nothing has changed. And yet it is hard to deny the feeling that we are at an inflection point in sports. Partly, that is because the old guard is saying goodbye and we are entering new eras.

This year, Lionel Messi and Cristiano Ronaldo, the two athletes with the largest followings in the history of the world, likely played in their last World Cup. Roger Federer is gone, and Rafael Nadal is nearing the end of his career; Serena Williams announced her retirement, in August. The most successful quarterback in N.F.L. history, Tom Brady, retired—only to unretire a month later, though at times this season he has looked as if he wished he were on a beach somewhere instead. (At other times, he has been leading fourth-quarter comebacks.) LeBron James is still playing like a perennial M.V.P. candidate, but the N.B.A. no longer orbits around him, as it once did. Sue Bird and Sylvia Fowles left the W.N.B.A., finishing as two of the best ever to play. The snowboarder Shaun White finished his career; the heavyweight champion Tyson Fury did, too—only, like Brady, to change his mind.

As always, in sports, there’s a new generation right behind these athletes. The N.F.L. has a new brigade of electric young quarterbacks: Lamar Jackson, Joe Burrow, Josh Allen, and Patrick Mahomes. In the N.B.A., Ja Morant, Jason Tatum, Luka Dončić, and other charismatic young superstars are not even twenty-five years old. Carlos Alcaraz, the new No. 1 in men’s tennis, won a Grand Slam, and yet is just arriving. On the women’s side, Iga Świątek, at the age of twenty-one, just had the most dominant season since Williams’s performance in 2013. May Shohei Ohtani be in his prime forever.

It’s invigorating to watch these new stars move with the grace granted to those just discovering their power. But the illusion of immortality has a flip side. Fans mark their lives by the seasons of sports and the careers of athletes. Even a perfectly choreographed retirement, achieved after a bountiful career, can be experienced as a kind of loss. And watching a star leave one life behind for whatever comes next can prompt our own questions about accomplishments, and what they mean. In 2021, nearly fifty million Americans quit their jobs, and, according to one global survey, more than forty per cent of people in the workforce around the world considered it. The trend, which one social scientist dubbed “the Great Resignation,” continued this year, when we also saw a spike in labor strikes. The explanations for the phenomenon are murky and manifold: a reflection of better opportunities for some and impossible burdens for others. It also seemed, in some cases, connected with a post-pandemic reconsideration of what matters.

Superstar athletes, of course, don’t quit quietly. They have little in common with the job-switching and labor-force exits experienced by the rest of us. Still, it seems right that they should inspire some kind of existential reflection. After all, much of what we celebrate in athletes and coaches is, viewed from another angle, unhealthy: the obsessive devotion to craft, above responsibilities to friends and families; the ability to regularly withstand degrees of physical and mental pressure and pain that perhaps none of us should have to experience; the habit of connecting winning to one’s sense of worth. The effects of social media, the rise of sports gambling, and the injection of incredible amounts of money have only increased the stakes, and, in some cases, the hate that athletes are exposed to. Shaw saw it happen in his time at Stanford. “Even opinions on social media aren’t even really opinions. They’re just bait, venom,” he told me.

In early December, ESPN published a piece by Seth Wickersham in which Luck, Shaw’s old quarterback, spoke at length for the first time about his abrupt retirement. In the piece, Luck explained what he had previously only privately admitted to himself and a handful of others: the problem with being an N.F.L. quarterback wasn’t just the pain of contusions and torn cartilage. It was that achieving excellence required, or seemed to require, becoming controlling, self-absorbed, at once arrogant and anxious—someone he didn’t want to be.

Athletes are often élite at compartmentalizing. Single-minded, they think in terms of sacrifices, but sometimes selfishly. They all experience the grind of preparation, and are subject to fans’ gladiatorial demands. And yet, set against that, are the sports themselves: the display of skills, of physical and mental mastery, of the satisfactions of coöperation and competition, of joy, pure and simple. Luck, as Wickersham describes, couldn’t stay away from football. He started talking about football with his old coach in Indianapolis, and with Shaw, he told Wickersham; he has gone back to graduate school at Stanford, and now talks of wanting to be a teacher and a coach.

Luck’s old coach, for his part, is looking forward to dropping his son off at college and having the chance to visit a few universities with his daughter as she decides where to apply. Shaw wants to be in the stands at his son’s track meets. Maybe he’ll write a book, or be an analyst, or return to coaching one day. He has always wanted to make sure that there is “a line between who I am and what I do,” and, as much as he says he loves Stanford, admits to some relief in feeling as if he can separate his job from his identity. (Wickersham asked Luck how much of his sense of self was wrapped up in being a Q.B. “A lot,” Luck replied. “A lot. A LOT. And I didn’t realize that until after the fact.”) Shaw told me that he was still processing the strangeness of the shutdown. And he pushed back against the idea that everything had returned to the way it had been before the pandemic. “I don’t fight the fact that major things should change us,” he said. “I expect us to be a different version of ourselves.” ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com