This story is part of a group of stories called

Finding the best ways to do good.

The US is now in the middle of what can only be described as a national Covid-19 epidemic, with cases across the country rising at alarming rates in recent weeks.

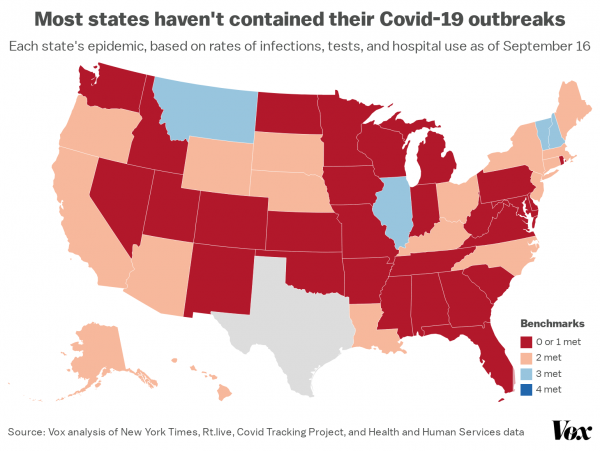

Public health experts look at a few markers to determine how bad things are in each state: the number of daily new cases; the infection rate, which can show how likely the virus is to spread; the percentage of tests that come back positive, which should be low in a state with sufficient testing; and the percentage of hospital beds that are occupied by very sick patients.

A Vox analysis indicates the vast majority of states report alarming trends across all four benchmarks for coronavirus outbreaks. Most states still report a high — sometimes very high — number of daily new Covid-19 cases. Most still have high infection rates. Most still have test positive rates that are too high, indicating they don’t have enough tests to track and contain the scope of their outbreaks. (The US overall has seen a decrease in new cases in recent weeks, but the numbers are still much too high.) And most still have hospitals with intensive care units that are too packed.

Across these benchmarks, no state fares well on all four metrics, which means no state has its epidemic fully under control right now. (Texas is excluded due to recent changes in how it reports tests.)

Only the Northeast currently seems to be doing better overall after a resurgence of Covid-19 cases. But that region, particularly New York City, was hit hard by the initial wave of the Covid-19 pandemic, with New York reporting the highest overall death toll for the country so far.

The current national outbreak, reaching from California to Florida, is the result of the public and its leaders collectively letting their guard down. States, with the support of President Donald Trump, moved to reopen — often before they saw sizable drops in daily new Covid-19 cases, and at times so quickly they didn’t have time to see if each phase of their reopening was leading to too many more cases.

The public embraced the reopenings, going out and often not adhering to recommended precautions like physical distancing and wearing a mask.

It’s this mix — of government withdrawal and public complacency — that experts have cited again and again in explaining why states are now seeing a resurgence in Covid-19 cases.

“It’s a situation that didn’t have to be,” Jaime Slaughter-Acey, an epidemiologist at the University of Minnesota, told me. “For almost three months, you had opportunities to be proactive with respect to mitigating the Covid-19 pandemic and to help normalize culture to adopt practices that would stem the tide of transmissions as well as the development of Covid-19 complications. … It was not prioritized over the economy.”

The effects are felt not just in terms of more infections, critical illnesses, new chronic conditions, and deaths, but in the long-term financial impact as the economy starts shutting down again, people refuse to go out, and businesses resist reopening during a pandemic.

“Dead people don’t shop. They don’t spend money. They don’t invest in things,” Jade Pagkas-Bather, an infectious diseases expert and doctor at the University of Chicago, told me. “When you fail to invest in the health of your population, then there are longitudinal downstream effects.”

The benchmarks tracked by Vox don’t cover every important facet of the pandemic. They don’t show, for instance, how well a state is doing with contact tracing, when “disease detectives” track down people who may have been infected and push them to quarantine; the data for how states are doing on that front is still lacking. And some measures that are helpful for gauging if a state can safely start to reopen, like whether cases have fallen in the previous two weeks and total tests, are excluded to focus more on the status of each state’s current Covid-19 outbreak.

Together, these four benchmarks help give an idea of how each state is doing in its fight against Covid-19. Nationwide, it’s pretty grim.

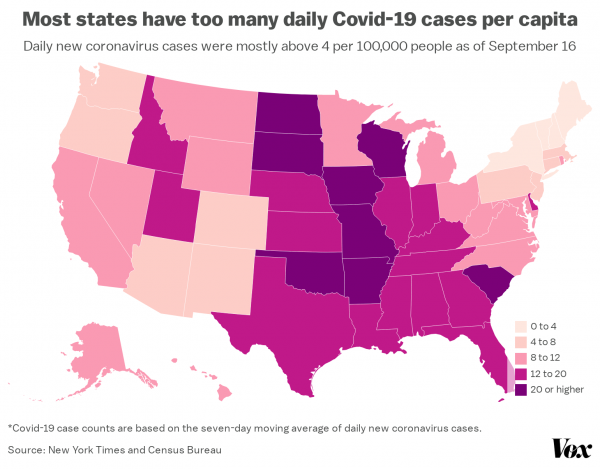

1) Most states have too many daily new Covid-19 infections

What’s the goal? Fewer than four daily new coronavirus cases per 100,000 people per day, based on data from the New York Times and the Census Bureau.

Which states meet the goal? Maine, New Hampshire, New York, and Vermont — just four states.

Why is this important? The most straightforward way to measure whether any place is experiencing a big coronavirus outbreak is to look at the number of daily new Covid-19 cases.

There’s no widely accepted metric for how many cases, exactly, is too many. But experts told me that aiming for below four daily new cases per 100,000 is generally a good idea — a level low enough that a state can say it’s starting to get significant control over the virus.

A big caveat to this metric: It’s only as good as a state’s testing. Cases can only get picked up if states are actually testing people for the virus. So if a state doesn’t have enough tests, it’s probably going to miss a lot of cases, and the reported cases won’t tell the full story. That’s why it’s important not to use this benchmark by itself, but to use it alongside metrics like the test positive rate.

Along those lines, the number of daily new cases may give a delayed snapshot of a Covid-19 outbreak. If test results take a week to get reported to the state, then the count for daily new cases will really reflect the state of the outbreak for the previous week.

If testing is adequate in a state, though, the toll of daily new cases gives perhaps the best snapshot of how big a state’s Covid-19 outbreak is.

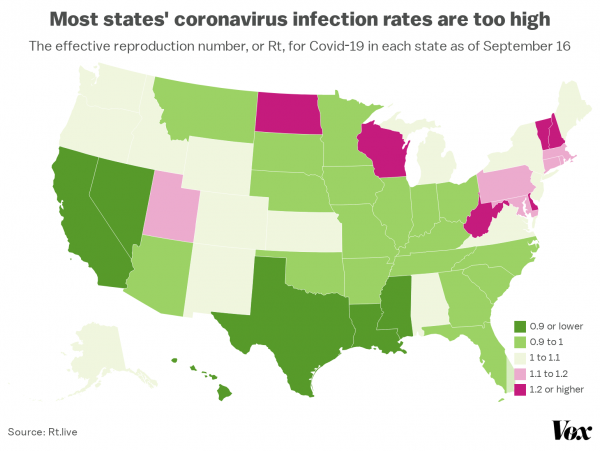

2) The coronavirus is spreading too quickly in many states

What’s the goal? An effective reproduction number, or Rt, below 1, based on data from Rt.live, a site created by two Instagram founders and a data analyst.

Which states meet the goal? Arizona, Arkansas, California, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Texas — a total of 24 states.

Why is this important? The Rt measures how many people are infected by each person with Covid-19. If the Rt is 1, then an infected person will, on average, spread the coronavirus to one other person. If it’s 2, then an infected person will spread it to two on average. And so on.

It’s an attempt, then, to gauge how quickly a virus is spreading. One way to think about it: Unlike the count for daily new cases, this doesn’t give you a snapshot of a state’s Covid-19 outbreak today, but where the outbreak is heading in the near future.

The goal is to get the Rt below 1. If each infection doesn’t lead to another, that would over time lead to zero new Covid-19 cases.

The estimated Rt can be very imprecise — with margins of error that make it hard to know for certain in any state if it’s really above or below 1. Different modelers can also come up with different estimates. That’s, unfortunately, just the reality of using limited data to come up with a rough estimate of a disease’s overall spread.

The Rt also reflects an average. If 10 people are infected with Covid-19, nine spread it to no one else, and one spreads it to 10, that adds up to an Rt of 1. But it masks the fact that individuals, for whatever reason, can still cause superspreading events — which seem of particular concern with the coronavirus.

Still, the Rt is one of the better measures we have for tracking a pathogen’s spread across the whole population. When paired with the other metrics on this list, it can give us a sense of each state’s outbreak now and in the future.

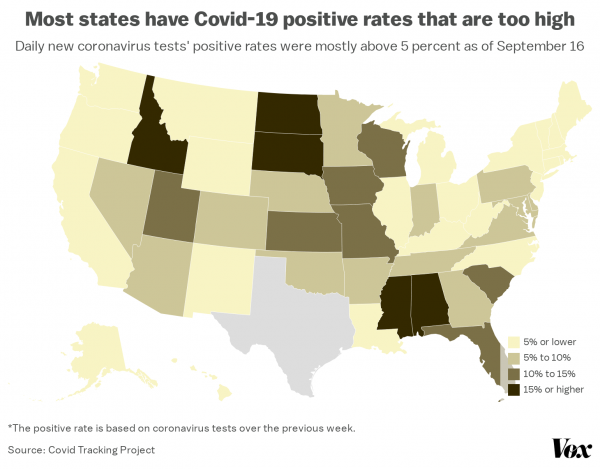

3) Most states’ positive rates for tests are too high

What’s the goal? Below 5 percent of coronavirus tests coming back positive over the past week, based on data from the Covid Tracking Project.

Which states meet the goal? Alaska, California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Illinois, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, Montana, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, Washington, West Virginia, and Wyoming — 23 states. Washington, DC, did as well. (Texas is excluded due to recent changes in how it reports tests.)

Why is this important? To properly track and contain coronavirus outbreaks, states need to have enough testing. There are all sorts of proposals for how much testing is needed in the US, from 500,000 a day to tens of millions.

But one way to see if a state is testing enough to match its outbreak is the rate of tests that come back positive. An area with adequate testing should be testing lots and lots of people, many of whom don’t have the disease or don’t show severe symptoms. High positive rates indicate that only people with obvious symptoms are getting tested, so there’s not quite enough testing to match the scope of an outbreak.

The goal for the positive rate is, in an ideal world, zero percent, since that would suggest that Covid-19 is vanquished entirely. More realistically, in a world going through a pandemic, the positive rate should be below 5 percent. But even if a state reaches 5 percent, experts argue it should continue trying to push that number further down, to match nations like Germany, New Zealand, and South Korea that have gotten their positive rates below 3 percent and even 1 percent, in order to truly get ahold of their outbreaks.

As long as a state is above 5 percent, chances are it’s still missing a significant number of Covid-19 cases. And the higher that number is, the more cases that are very likely getting missed.

So even if your state is reporting a low number of daily new cases, a high positive rate should be a cause for alarm — a sign that there’s an outbreak that’s only hidden due to a lack of testing. And if your state is reporting a high number of daily new cases and a high positive rate, that’s all the more reason for concern, suggesting the epidemic is even worse than the total case count indicates.

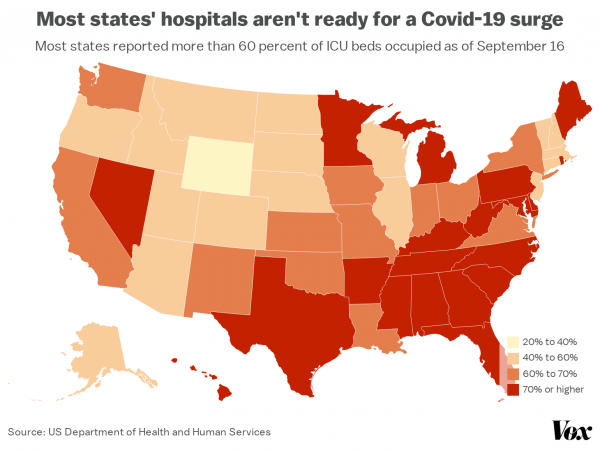

4) Most states’ hospitals don’t have much space for Covid-19 patients

What’s the goal? Below 60 percent occupancy of ICU beds in hospitals, based on data from the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Which states meet the goal? Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, Connecticut, Idaho, Illinois, Massachusetts, Montana, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, North Dakota, Oregon, South Dakota, Utah, Vermont, Wisconsin, and Wyoming — 18 states.

Why is this important? One thing the world has seen, from China to Italy to New York, is that Covid-19 can very quickly overwhelm hospitals. The consequences for this are dire: If any place has a big coronavirus outbreak, and there isn’t enough room in a hospital to treat patients, that could lead to worse outcomes, including death.

The occupancy rate in states’ intensive care units helps track how much space hospitals have to deal with more Covid-19 patients. It also gives a snapshot of just how busy states’ hospitals are on any given day.

Generally, the goal is to stay below 60 percent occupancy at ICU beds in hospitals. That’s a point when hospitals have enough cushion, experts say, to more effectively treat people as well as better handle a rush of patients should an outbreak get worse.

This is a bit of a lagging indicator for tracking an outbreak. Since people can take as long as weeks to develop Covid-19 symptoms once they’re infected, hospitalizations also take a few weeks to start trending up as cases trend up.

ICU occupancy also isn’t the only metric for tracking hospital readiness. The US Department of Health and Human Services also tracks the percentage of people in inpatient beds who have Covid-19 and the percentage of inpatient beds occupied in general. The other benchmarks also give a view of how well a state’s hospitals are handling a coronavirus outbreak.

Still, for a general idea of how bad a state’s Covid-19 outbreak is and how ready the state is to handle a surge in cases, the ICU occupancy rate is a helpful indicator. If a state’s ICUs are overwhelmed, the state is possibly experiencing a big epidemic, or at least not ready for one.

Help keep Vox free for all

Millions turn to Vox each month to understand what’s happening in the news, from the coronavirus crisis to a racial reckoning to what is, quite possibly, the most consequential presidential election of our lifetimes. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. But our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources. Even when the economy and the news advertising market recovers, your support will be a critical part of sustaining our resource-intensive work. If you have already contributed, thank you. If you haven’t, please consider helping everyone make sense of an increasingly chaotic world: Contribute today from as little as $3.

Sourse: vox.com