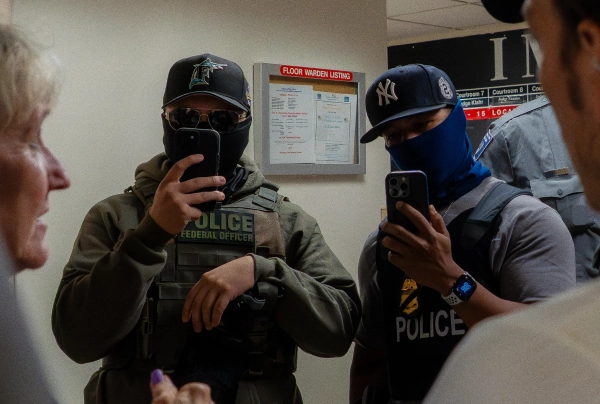

In early June, President Trump had federal officers use tear gas and rubber bullets to disperse a peaceful protest so he could stage a photo op outside St. John’s Church, which sits across from the White House.

The image, now infamous, shows Trump awkwardly holding up the Bible as though he’s never held a book in his life. It’s a surreal shot that somehow captures the performative dimension of his entire presidency.

But why the Bible? And why go through all that trouble to do the photo op in front of a church?

It’s well-known that evangelicals are one of Trump’s most loyal constituencies, but it’s still not clear why. Conventional wisdom says that evangelicals held their noses and voted for Trump purely for pragmatic purposes — the biggest reason being the Supreme Court. They may not like him, the argument goes, but he’s a useful political vehicle. (See, for example, the Court’s decision on Wednesday that allows the Trump administration to expand religious exemptions for employers who object to the Affordable Care Act’s contraceptive mandate.)

But what if Trump wasn’t a trade-off for evangelicals? What if an obsession with manhood and toughness made a figure like Trump the natural fulfillment of their political evolution?

This is the argument Kristin Kobes Du Mez, a historian at Calvin University, makes in her new book Jesus and John Wayne. According to Du Mez, evangelical leaders have spent decades using the tools of pop culture — films, music, television, and the internet — to grow the movement. The result, she says, is a Christianity that mirrors that culture. Instead of modeling their lives on Christ, evangelicals have made heroes of people like John Wayne and Mel Gibson, people who project a more militant and more nationalist image. In that sense, Trump’s strongman shtick is a near-perfect expression of their values.

To be candid, I wasn’t sure what to make of this thesis, but I’m also not an authority on American evangelicalism. So I contacted Du Mez, who teaches at a Christian college and has spent 15 years studying evangelicals, to talk about the direction of the movement and how it led to Trump and what she calls our “fractured political moment.”

A lightly edited transcript of our conversation follows.

Sean Illing

The contrarian argument at the core of your book is that the relationship between Trump and (mostly white) evangelicals is more harmonious than most people suggest. Can you sum up your thesis?

Kristin Kobes Du Mez

Well, there are all these theories that evangelicals were holding their noses when they voted for Trump, that they were somehow betraying their values. But I’ve studied evangelicals for a long time and I was watching them very closely during the election and in the aftermath, and I just didn’t see any regrets at all. There was no angst or no sense that this was somehow a difficult trade-off. In fact, what I saw was a bunch of enthusiasm. There were some evangelical leaders who were expressing caution about Trump, but most of the rank and file had zero difficulty supporting Trump.

Sean Illing

And when did that become clear to you?

Kristin Kobes Du Mez

I’d say right around the time the Access Hollywood tapes were released — that’s when it crystallized for me. So we had these tapes where Trump is talking about sexually assaulting women in such crass terms. And the media really homed in on white evangelicals at that moment, asking if this was a bridge too far. Although there was a little hesitation here and there from evangelicals, about a week later they were all back on board.

Sean Illing

I know you teach at a Christian university, but did you grow up in the evangelical world? Do you know it from personal experience?

Kristin Kobes Du Mez

I didn’t identify as an evangelical growing up, but most evangelicals don’t. We tend to identify as Christians. Looking back, though, I would probably define myself as evangelical-adjacent. I grew up in a small town in Iowa, and this was very much a part of my world.

As I grew up, I was exposed to this evangelical popular culture through our local bookstore, the only bookstore in town. The shelves were filled with these evangelical books, with Christian contemporary music and Christian movies. I was in a Christian youth group. And so my experience with evangelicalism was through the popular culture.

Sean Illing

Help me understand why masculinity and nationalism are so foundational to the contemporary evangelical worldview.

Kristin Kobes Du Mez

What I look to as a historian is this critical period in the post-World War II era when these gender ideals fuse with anti-communist ideology and this overarching desire to defend Christian America. The idea that takes root during this period is that Christian masculinity, Christian men, are the only thing that can protect America from godless communism.

At the same time, you have the civil rights movement destabilizing white evangelicalism and conceptions of white masculinity. Then you have feminism destabilizing traditional masculinity. And all of this comes together for evangelicals, who see their place in the culture slipping away, and they see their political power starting to erode because of this cultural displacement. That’s the moment when you see Christian nationalism linking together with a very militant conception of Christian manhood, because it’s up to the Christian man to defend his family against all sorts of domestic dangers in the culture wars, and also to defend Christian America against communists and against military threats.

Sean Illing

So the idea is that Christian masculinity is the only thing that can preserve traditional American culture and that belief is what precipitates the turn toward a more muscular Christianity?

Kristin Kobes Du Mez

That’s exactly right. So when you think of evangelicals, a lot of people think of the term “family values.” But I actually went back to the origins of family values evangelicalism and I was really surprised just how much it was placed in the context of foreign policy, how much it was in the service of defending the American nation. If you go back and listen to James Dobson of Focus on the Family and read the books that emerged during this period, this is all very clear.

Sean Illing

The phrase “family values” is typically hurled at evangelicals in order to call out their hypocrisy, but I think your book makes pretty clear that they’re not hypocrites at all. They only appear hypocritical if you misunderstand what they actually value.

Kristin Kobes Du Mez

Exactly. If you understand what family values evangelicalism has always entailed — and at the very heart of it is white patriarchy, and often a militant white patriarchy — then suddenly, all sorts of evangelical political positions and cultural positions fall into place.

So evangelicals are not acting against their deeply held values when they elect Trump; they’re affirming them. Their actual views on immigration policy, on torture, on gun control, on Black Lives Matter and police brutality — they all line up pretty closely with Trump’s. These are their values, and Trump represents them.

Sean Illing

I’d like to steelman the evangelical perspective, so can you tell me what cultural forces they’re reacting against?

Kristin Kobes Du Mez

Well, it changes over time. In the ’40s and ’50s, it’s all about anti-communism. But once the civil rights revolution takes hold, it becomes about defending the stability of the traditional social order against all the cultural revolutions of the ’60s. But the really interesting moment for me is in the early ’90s when the Cold War comes to an end. You would think there would be a kind of resetting after the great enemy had been vanquished, but that’s not what happened.

Instead, we get the modern culture wars over sex and gender identity and all the rest. And then 9/11 happens and Islam becomes the new major threat. So it’s always shifting, and at a certain point I started asking the question, particularly post-9/11, what comes first here? Is it the fear of modern change, of whatever’s happening in the moment? Or were evangelical leaders actively seeking out those threats and stoking fear in order to maintain their militancy, to maintain their power?

Sean Illing

So this drift into a more militant and nationalist Christianity leads to this obsession with toughness and machismo. The way you put it is that evangelicals are looking for “spiritual badasses.” They don’t want gentle Jesus, they want William Wallace or John Wayne.

Kristin Kobes Du Mez

Yeah, these are their role models. Most white evangelical men that I knew during the height of this movement, which is really the early 2000s, were very militant. They were buying these hypermasculine books and taking part in these men’s reading groups. They weren’t living out this rugged, violent lifestyle, except maybe at weekend retreats where they role-played this stuff. But in real life, they were still walking around in khakis and polo shirts, but these were the values that were really animating their worldview.

Sean Illing

Wait, are there weekend retreats where evangelical men are role-playing Braveheart?

Kristin Kobes Du Mez

I don’t know about that in particular, but this is very much a thing. The success of John Eldredge’s book Wild at Heart [a huge bestseller that urged young Christian men to reclaim their masculinity] was a big deal in the evangelical world, and it sold millions of copies just in the US. Every college Christian men’s group was reading this. It was everywhere in the early 2000s.

There were lots of conferences celebrating this version of a rugged Christianity. It was big business, and there were lots of weekend retreats where men could go out into the wilderness and practice their masculinity. Local churches invented their own versions of this. One church I know in Washington had their own local Braveheart games that involves wrestling with pigs or something. It was all weird and different, but the point was to prove and express your masculinity.

Sean Illing

Is this fascination with manhood unique to evangelical culture in particular? Or is this something you find in other Christian subcultures?

Kristin Kobes Du Mez

The emphasis on strict “gender difference” and perceived need to “define” Christian manhood is far greater in conservative white evangelicalism than in other Christian subcultures. White evangelicals also stand out in terms of their emphasis on militancy and their conceptions of masculinity, and in how that militant masculinity is connected to Christian nationalism.

In Black Protestantism, for example, you may find an emphasis on Christian manhood, but you’re much more likely to encounter discussions of fatherhood rather than a militant warrior masculinity. In mainline Protestantism you’ll be more likely to encounter a kinder, gentler masculinity — more of the Mr. Rogers sort. (Militant white evangelical masculinity explicitly denounces Mr. Rogers’s model of manhood.)

That said, evangelical constructions of masculinity have made inroads into mainline circles largely via popular culture (many mainline churches use evangelical literature in their small-group Bible studies, for example), so the lines between white evangelical and mainline Christianity are not always all that clearly drawn.

Sean Illing

There’s a lot going on there, but I’ll bring this back to Trump. Do most evangelicals consider him a spiritual badass?

Kristin Kobes Du Mez

For many he’s not, but he is their great protector. He’s their strongman that God has given them to protect them. So, again, the ends justify the means here. But I think it’s important to understand that the appeal of Trump to evangelicals isn’t surprising at all, because their own faith tradition has long embraced this idea of a ruthless masculine protector.

This is just the way that God works and the way that God has designed men. He filled them with testosterone so that they can fight. So there’s just much less of a conflict there. The most common thing that I hear from white evangelicals defending Trump is that they just wish he would tweet less. I don’t find a lot of concern about his actual policies or what’s in his heart.

Sean Illing

I don’t understand how a draft-dodging, spray-tanned hypochondriac has become a hypermasculine protector for militant evangelicals —

Kristin Kobes Du Mez

I mean, that’s fair, but you have to remember that their whole idea of militant masculinity was formed in reaction against feminism and more recently against so-called political correctness. That has been just such a powerful enemy for white evangelicals who feel oppressed by these new standards of behavior. And I think Trump really succeeds by not following any of those rules of civil discourse.

Sean Illing

If most evangelicals are taking their moral and political cues from Trump or the Duck Dynasty clan or from Christian radio and television, haven’t we crossed over into something post-religious, something closer to a lifestyle or a cultural pose?

Kristin Kobes Du Mez

I think we have. But I will say there is still diversity within evangelical churches, communities, and families. There are so many evangelicals who read their Bible every morning, who hold to scriptural teachings as they understand them. But for many of them, the Bible is a complicated book. Which verses do you hold on to as formative for your life, and which do you dismiss? Many are reading through the filter of this ideology now.

But I’ve encountered lots of evangelicals who don’t want to speak out, who feel a lot of pressure within their own communities. This is not what their faith means to them, this is not what Christianity is to them. So when we talk about white evangelicals, we should acknowledge that there is disagreement within churches and communities and families, but it’s true that a solid majority of white evangelicals have bought into this ideology.

Sean Illing

One of the most interesting threads in your book is this story about how evangelical leaders have tried to modernize the church by using pop culture to lure people in, but over time the pop culture has completely supplanted the theology and all that’s left is the vacuous political brand.

Kristin Kobes Du Mez

I teach at a Christian university, so the majority of my students would fit into this category of white evangelicals. And just this past year, I was teaching a course where it involved reading the first three chapters of Genesis. It was about biblical gender roles and taking a critical look.

And at one point during our discussion, one woman raised her hand and said, “I have a confession to make. I think this is the first time I’ve actually read the first three chapters of Genesis … I’ve been working with the VeggieTales stories and I assumed I knew this, so I didn’t bother with the Bible.” [VeggieTales is a Christian animated series for kids that uses pop culture to retell biblical stories.] She was so embarrassed to confess that, but then several other students confessed to the same thing.

So this is the evangelical culture these kids have been raised in. They listen to pop Christian music on the radio. They read the pop Christian books. They watch Focus on the Family children’s programming. They watch VeggieTales cartoons. And Christian parents are told to keep their kids away from the broader secular culture, so it’s also very insular. They stick to the Christian version of it. That’s the only theology they know.

Sean Illing

This is really a story about a religious movement getting entangled with politics and consumerism and being bastardized as a result of the collision.

Kristin Kobes Du Mez

I think that’s right, and there’s a lot of money to be made through the book sales, the advertising, and the connections between the political strategists and some of the folks behind this consumer market. What I really tried to do here is just understand the networks behind American evangelicalism. Who is publishing what? What are the distribution networks?

It’s critical to understand evangelicalism through this lens. Even when someone walks into a Christian book store or goes online and orders a Christian product, that feels like an authentic expression of their faith to them.

Sean Illing

I hear people say all the time that Trump’s election was a tragedy for evangelicals, but after reading your book, I wonder if it isn’t their greatest victory.

Kristin Kobes Du Mez

It depends on your vantage point, right? I’ve been studying evangelical masculinity for almost 15 years, and seeing the veil ripped off in this way was almost cathartic for me. I was able to see the nature of the movement with even more clarity. This is what “family values” evangelicalism looks like, and now it’s apparent to everyone.

But for evangelical dissenters, this is indeed a tragedy. And yet I think even those who are resisting, or who are calling this out and who are struggling with the direction that evangelicalism has taken, still need to reckon with the ways in which they, too, as part of this tradition, have been complicit in this ideology. The Trump era didn’t just happen. We’ve been moving in this direction for a long time.

Support Vox’s explanatory journalism

Every day at Vox, we aim to answer your most important questions and provide you, and our audience around the world, with information that has the power to save lives. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. Vox’s work is reaching more people than ever, but our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will enable our staff to continue to offer free articles, videos, and podcasts at the quality and volume that this moment requires. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today.

Sourse: vox.com