The easiest question to answer about Quibi is the one I’m most frequently asked: Just what is Quibi, anyway?

Quibi is short for “quick bites” — though you don’t pronounce it “quih-bye” (to rhyme with “rib-eye”) but, instead, “quih-bee,” to rhyme with the name “Libby.” It’s a new streaming service built from the ground up for mobile devices, and some of the names behind it include media mogul Jeffrey Katzenberg (who worked at Disney Animation during its renaissance, then started Dreamworks Animation and was instrumental in making such films as Shrek and Prince of Egypt) and CEO Meg Whitman, who is the former CEO of eBay.

There’s a lot of money behind Quibi: As The Verge pointed out just last month, the service had raised nearly $2 billion in seed money before anybody saw a single frame of programming. With that much cash in its coffers and with folks like Katzenberg and Whitman involved, you’d expect Quibi to be new and original, wildly innovative, or at least stuffed full of great programming.

Quibi is none of those things. Its central aim is to present short-form programming, so every episode of every one of its shows is under 10 minutes long, and many are quite a bit shorter than that. (I watched a couple in the five-minute range.) Quibi’s embrace of short-form content is supposed to be its killer new idea, the must-see that will compel you to pony up $5 a month to watch with ads and $8 a month to watch without. (Vox Media, the parent company of Vox, is creating programming for Quibi. I haven’t seen Speedrun, its daily show premiering Monday.)

But in practice, Quibi largely fails to differentiate itself from many other streaming services. At best, it’s like a YouTube you have to pay for.

Quibi’s programming ranges from reality show reboots to bland scripted shows to Nicole Richie making fun of herself

I spent the better part of a workday watching several of Quibi’s new series. The service sent me screeners of nearly 30 shows, usually providing three or four episodes of each. (Several programs that will run daily, to report or comment on the news, were not available, for obvious reasons.) The offerings ranged from reality competition series to game show reboots to scripted dramas to a very odd mockumentary. They were almost all mediocre. Some were terrible.

The most notable titles for many who sign up for Quibi’s 90-day free trial will be two remakes of old MTV shows — the prank show Punk’d (hosted by Chance the Rapper in this incarnation) and the dating show Singled Out (hosted by Keke Palmer and Joel Kim Booster). Neither program is bad, exactly, but neither program does much to explain why it’s been revived for 2020, either; if Quibi wants to ride the nostalgia boom, it’s not immediately clear why the programs it’s resurrecting are going to have the most immediate appeal for 20- and 30-somethings who are already inundated with streaming services aimed directly at them.

The other reality programming is … fine, but it’s clear that no one has put much thought into why it should exist in Quibi’s “quick bite” format. Reality television is often concept heavy — meaning a show can live or die based on the clarity of the concept for a series or episode — and in the sub-10-minute running time of Quibi episodes, generally all there’s time to do is introduce that concept before rushing through a quick conclusion. Many of the Quibi reality shows I screened made me feel like I was starting to get interested right before they abruptly ended.

The scripted series fare no better. All of them are structured less like episodic TV shows and more like a movie arbitrarily broken up into chunks. This is probably the right approach — a 10-episode Quibi show composed of 10-minute episodes will run 100 minutes, after all — but few of the programs have really thought through what that might look like. I more or less enjoyed its spin on Most Dangerous Game, with Christoph Waltz as the grinning villain who wants to hunt a man (in this incarnation named Dodge because he has to dodge all those murder attempts), and Flipped, an absurdist comedy I’m not sure I can describe but one that makes great use of Will Forte and Kaitlin Olson.

And yet these “pretty okay” shows were stacked up against a program called Survive, which I’d call one of the most irresponsible TV shows I’ve ever seen. About halfway through the show’s first episode, its protagonist (played by Game of Thrones star Sophie Turner) describes at length detailed instructions for both self-harm and suicide, in a way that makes self-harm and suicide seem vaguely alluring. It’s supposed to be dangerous and edgy; instead, it functions as an impromptu how-to manual that seriously crossed the line for me.

The one Quibi show I wholeheartedly enjoyed was the Nicole Richie mockumentary Nikki Fre$h. It has something to do with Richie trying to make herself relevant again by dubbing herself “Nikki Fre$h,” and becoming a rapper but also a beekeeper? It makes sense in the moment, but good luck explaining it to anybody. I just know that a major cameo in the third episode, one I dare not spoil, made me laugh uproariously — the only time a Quibi show elicited such a reaction from me.

So if Quibi’s shows aren’t worth it, is the service itself? With the caveat that I haven’t actually seen the interface the new service will use — and maybe it will be extraordinary — I’m confident there’s nothing on Quibi that isn’t already being done better elsewhere, and often for much cheaper.

Quibi is selling itself as revolutionary. But most of its innovations were pioneered by other services.

The various screeners Quibi provided to critics showed us each program in both vertical and horizontal orientations, so we could get an idea of how its shows will look depending on how you hold your phone:

Every single Quibi show has been considered from the perspective of someone who’d watch in a vertical orientation, as well as from the perspective someone who’d watch in a horizontal orientation. But the narrow framing of vertical orientation often leaves important visual information cropped out anyway, or it creates unintentionally unsettling images, like the contestant looming in the background of the shot above. Particularly in some of Quibi’s more documentary-style programming — where the camera has to dart around to follow what’s happening — the vertical orientation proved difficult to watch.

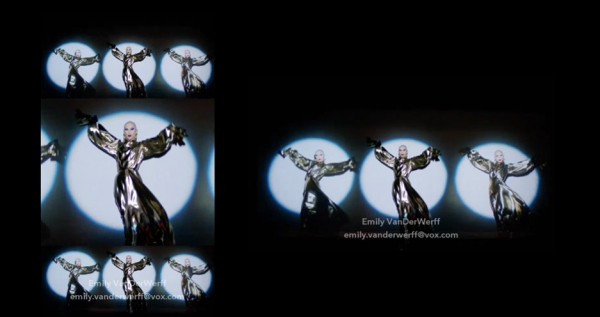

A few programs found a fun way to present information in the vertical orientation, occasionally using a split-screen effect where multiple people onscreen at the same time would appear in different frames stacked on top of each other. Here’s an example of that format in the show Nightgowns, a boring but beautifully filmed series about drag:

Rather than follow the entire performance of drag queen Sasha Velour — who would be moving all over the stage — the vertical orientation splits it up in a way that gives you the feel of the entire performance while allowing the camera to remain mostly stationary. Unfortunately, it’s the only Quibi show I watched that seemed to have thought about how differently such a performance would play out when watched on a phone.

This attempt to accommodate to vertical orientation viewers, I think, will be the difference most people notice when they fire up Quibi. And it might seem incredibly innovative to many of them. I don’t want to sell Quibi short here — the effort made to think about how people holding their phones vertically will experience its programming is welcome, even if it’s yielded far too many shows that just restrict all the action to the center of the frame. But it’s not exactly new.

And that’s the big problem with Quibi: Everything it does that’s interesting is already being done better by somebody else. A lot of the shows feel like lesser, shorter versions of more successful Netflix offerings (for instance, a show about how various pastas get their shapes is okay and all, but it has a pretentious vibe that Netflix’s similar Salt Fat Acid Heat mercifully avoided). And the shows that don’t feel like Netflix knockoffs are exactly the sort of scripted filler that tends to pad out new streaming platforms in need of content.

But look beyond Netflix and you’ll find other streaming services delivering even better results on Quibi’s core promises.

Quibi is a bunch of short-form content mostly aimed at young people — which makes it a lot like YouTube with more curation, better production values, and occasional celebrities. It’s not immediately clear what Quibi’s Punk’d remake adds to the world that Logan Paul didn’t, other than the chance to see bigger names getting pranked. Similarly, a pop culture rundown show called Memory Hole is no different from hundreds of YouTube videos providing fun looks back at obscure cultural moments, except it’s hosted by Will Arnett instead of an unknown narrator.

And YouTube, at least in its base form, is free. It’s also widely beloved by the teens and 20-somethings Quibi seems to be targeting. So Quibi is basically running straight at YouTube with a service that will cost money, for programming that is rarely much better than the best YouTube has to offer but features faces you (and by “you,” I mean an adult who’s not enmeshed in the world of YouTube celebrity) might recognize more.

Then there’s Snapchat, which remains enormously popular with teens and early-20-somethings. Snapchat also offers original series — ones that can only be watched vertically, and that have been better designed to play specifically on a phone. They’re TV shows or movies divided into smaller chunks, as Quibi’s shows often seem to be. And they’re free.

Snapchat’s shows have deliberately considered what it means to air on a phone screen and how information might best be conveyed. The use of split-screens on a Quibi program is still a tentative thing; on Snapchat, it happens in every single program.

And Snapchat’s approach is working, at least according to its internal numbers. Writes Vulture’s Kathryn VanArendonk:

Even if we assume that Snapchat is overreporting its numbers — because it probably is — there’s still a staggering number of people, mostly young adults and teens, watching its programming. Those are the same people Quibi is targeting, and if they’re already watching Snapchat, it’s hard to imagine them being sucked in by Quibi. (I don’t precisely like Snapchat’s shows, but they are relentlessly designed to do what they do perfectly. I can respect that.)

So if Quibi’s target audience is mostly occupied on other apps, and if the service isn’t that innovative, and if its programming is mostly unremarkable, why are we talking about it?

Media coverage of Quibi underlines the broken ways we talk about tech and entertainment

In the spring of 2019, a new streaming service called Nebula kicked off what’s called a soft launch, going online with a small amount of content with the idea that it would add more and more in the weeks to come. Nebula is another streaming service attempting to do “YouTube but better,” and the concept behind it is literally to pay prominent YouTube creators (with money pooled from the service’s $3-a-month subscriber base) to make what they’d love to if they weren’t reliant on the whims of the YouTube algorithm. (I should note here that one of those creators, Lindsay Ellis, is a friend of mine. She is also the only reason I know Nebula exists, which is going to become important in a moment.)

I don’t know that Nebula is presenting itself as something different in the way Quibi is, but it’s definitely trying something new. And yet it received maybe a hundredth of the press coverage that Quibi has. If you Google it, you’ll find a handful of news articles about the service, and then a bunch of confused Reddit threads asking what Nebula even is. Nebula hasn’t ever contacted me to offer screeners or access to the site. It’s unlikely it ever will. My guess is that whatever budget Nebula has, it isn’t being spent on publicists.

Quibi — which, again, has nearly $2 billion in capital — has been covered breathlessly from almost the moment it was announced. It aired ads during the Super Bowl. Its shows involve big Hollywood stars. It’s the kind of streaming service those of us who write about entertainment or tech are “supposed” to cover. But why? Why waste so much ink on something that feels so bizarrely underconsidered?

To me, Quibi is clearly inferior. It’s “more expensive YouTube” at best and “Snapchat but with worse quality control” at worst. It’s difficult to imagine a huge number of people who are looking to subscribe to yet another streaming service deciding to add Quibi. It’s also difficult to imagine many viewers subscribing to a streaming service specifically targeted at people who might want to watch short videos while on the go, given that said service is launching during a pandemic that is forcing everyone to stay home. (The pandemic isn’t Quibi’s fault, of course; the service’s April 2020 launch date was announced months ago. But now the pandemic is another thing standing in Quibi’s way.)

My point is that the reason Quibi has been covered so heavily has little to do with its ideas (which are paltry) or its programming (which is bad) or its business model (which is basically the same as every other streaming business model). The reason Quibi has been covered so heavily is that a lot of money has been sunk into it, and the people who started the service have previously made lots of money doing other things. Therefore, it must be important, because a capitalist society assigns value in terms of dollars.

I am aware that I am part of the problem. Look how many words I’ve written about Quibi, a service I clearly don’t like. That’s because I know there will be Quibi ads everywhere, and I know that enough people will say, “What’s Quibi?” and click on this article to find the answer. That’s the way the system works.

But it’s also a system that is so frequently hijacked by money as to have become functionally meaningless. In a world where news and entertainment moved at a rate slower than hyperspeed, I might have found a way to write about Quibi six months from now, after it had some time to settle in and become a part of some people’s lives. But in this world, the window of attention for Quibi is right now, and so here is this article. And in six months, some other new streaming service will come along.

I don’t know if Nebula is any better than Quibi. I do know there’s nothing on Quibi that other services aren’t already doing better. There are so many great niche streaming services out there, but none of them have the massive marketing budgets to get stuck in people’s brains the way Quibi does.

Quibi does not de facto have value because it’s spent enough money to convince people it has value. It is a flawed product, starting from a flawed premise, and the idea that it is worth talking about because it has purchased your attention (and mine) is so much of what’s wrong with America in the 21st century. The service is another naked emperor in a land full of them. So why are we looking for cool new fashions when the bare ass is visible from miles away?

Sourse: vox.com