Today, we face a conundrum. On one hand, we disagree on many important subjects: what to do about climate change, criminal justice reform, and whether or not to impeach our current president. On the other hand, there are high costs to verbalizing an opinion deemed “wrong.”

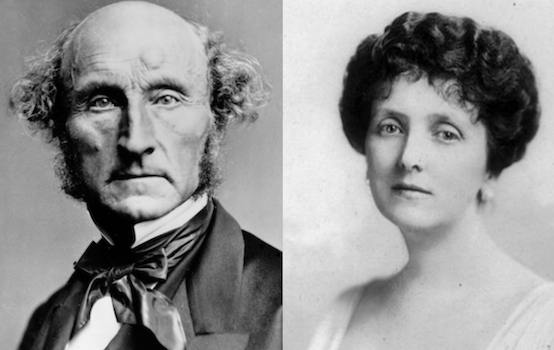

Often people respond to this tension by running to two extremes—either choosing flout norms of civility entirely, or conformity for the sake of social harmony. Yet neither view is precisely right and we should instead actively seek to synthesize them. To do so, we can look to the lives and thought of two important figures not often thought of in conjunction: John Stuart Mill (May 20, 1806—8, May 1873) and Emily Post (October 27, 1872—September 25, 1960), that latter’s day of birth we have the chance to commemorate just a few days ago.

John Stuart Mill the godfather of 19th century classical liberalism, was no fan of conformity. “He who does anything because it is the custom, makes no choice. He who lets the world choose his plan of life for him, has no need of any other faculty than the ape-like one of imitation,” he wrote in On Liberty.

Emily Post, godmother of 20th century etiquette, took the opposite view. “Try to do and say those things only which will be agreeable to others,” was Post’s axiom of conversation. Well-mannered folk, she argued, should “follow the customs of the locality in which they live. In other words to do exactly as your neighbors do.”

Advertisement

One can imagine Mill recoiling at Post’s axiom of conversation: “Try to do and say those things only which will be agreeable to others.” In her second edition of Etiquette, Post claims that “all well-bred persons” should “follow the customs of the locality in which they live. In other words to do exactly as your neighbors do is the only sensible rule.”

It is no surprise that Mill thought of conforming to norms as a procrustean bed. His interest in free expression and individuality was largely a response to his upbringing in Victorian England governed by strict codes of conduct that governed every aspect of life. He famously condemned the social expectations of his day: “Its ideal of character is to be without any marked character; to maim by compression, like a Chinese lady’s foot, every part of human nature which stands out prominently, and tends to make the person markedly dissimilar in outline to commonplace humanity.”

In Mill’s Victorian era, it was a “deadly crime” to smoke in the streets—at least in daylight—and wearing yellow gloves instead of white was social suicide, according to the The Habits of Good Society: A Handbook of Etiquette for Ladies and Gentlemen, a popular manual from the 1850s. Cassell’s Household Guide, an 1869 book of Victorian etiquette, outlines in painful detail the interaction between a single man and women on the street—it’s rude to ignore one another, and of course “Strict reticence of speech and conduct should be observed in public,” being sure to avoid “loud talking” and “animated discussions.” And can you imagine a world where ladies were prohibited from enjoying more than one glass of champagne? I for one, cannot.

Yet still Post’s admonition to play by the rules of society as others do has some merit. Abiding by norms—and not flouting them unnecessarily—shows that no citizen thinks they are above the rules, and is an important way to build social trust. This social trust is the basis of a free and truly civil society, not to mention free markets, past and present.

As Reason editor-at-large Matt Welch recently argued, social trust between citizens, is important and a derth of it is problematic to a free society. “We are careening dangerously from a high-trust to a low-trust society. We trust one another less, we trust government and other mediating institutions less,” Welch wrote for the L.A. Times.

The consequences of this lack of trust are bleak. High trust societies have less crime, corruption and generally lower transaction costs because they’re not paranoid about being taken advantage of by their government and fellow citizens. Conversely, he explains, low trust societies don’t develop the institutions of civil society—the institutions that Tocqueville so eloquently praised in America—because people don’t like being around one another. Conformity and playing by society’s rules of propriety—not cutting someone off in traffic, waiting in line instead of jumping to the font because you’re in a rush—communicate wordlessly that one thinks of themselves as part of the team.

Trust among citizens and civil society are also a necessary buttress against centralized state power: it is the cumulative effect of our everyday decisions to act well and courteously toward one another in our everyday interactions that allows our government to stay limited in nature. When we don’t, and our everyday exchanges disintegrate, people unfailingly cry for government interference—as we saw with Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s “politeness campaign.”

The answer is neither the blind conformity that Post advocated, nor unquestioning anti-conformity Mill championed. It’s important to be thoughtful about why our norms exist, and to question them regularly to ensure they still serve their purpose: of facilitating human relationship and community and flourishing—not quelling it by smothering individuality.

Though a hardline nonconformist in theory, one can imagine Mill having some wiggle room in practice. For example, Mill revered English writer Thomas Carlyle—author of the famed work On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and The Heroic in History—and one day when Carlyle was visiting Chez Mill, Mill’s kitchen caught fire and destroyed the only copy of Carlyle’s history of the French Revolution! Mill of course made the necessary apologies and Carlyle—which was surely in part because of his naturally embarrassment but also because of the social expectations around the duties of a host and guest. Carlyle was gracious about the affair and the two went on being friends (eventually parting ways, however, over Carlyle’s racist beliefs).

John Stuart Mill, above all, was averse to dogma—including his own. Meanwhile, Emily Post, of course could have stood to loosen up a little.

Let us learn from them both. How might we do this? Mill’s attraction to nonconformity would seem to have a good application in politics and economics; think of the way we delight in political independence from partisan hackery and celebrate disruptive technology. Post’s insistence on social norms could find worthy application in the way we engage each other in culture and everyday life (especially social media), and go a long way toward helping to shore up the social institutions we desperately need to buttress our resistance to political demagoguery.

Alexandra Hudson is a writer and former federal civil servant. She lives in the American Midwest, is a research fellow at the American Institute for Economic Research ,and contributes to The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Examiner, and The Hill. Follow her on Twitter @LexiOHudson.

Sourse: theamericanconservative.com