Gold is once again shining in the eyes of investors – not as a relic of the past, but as a real answer to contemporary fears. Although the “barbaric relic” does not pay interest, its performance in the face of wars, crises and inflation is a reminder that in a world dominated by uncertainty, gold remains the ultimate reserve of value.

Gold has been a safe haven in uncertain times for centuries. In ancient times, it was considered a symbol of power, might, wealth and prosperity. Today, the price of gold is particularly sensitive to geopolitical tensions, wars and recessions. Gold does not pay interest, but it offers something more important – a sense of security in times of chaos.

The formation of gold prices is also influenced by the macroeconomic situation, including the level of inflation and interest rates – usually the prices of the “barbaric relic” increase when interest rates fall and the yield on securities decreases or when the purchasing power of money decreases due to high inflation. Gold is also an alternative to deposits in a period of falling confidence in the stability and security of banking operations.

“Given its unique characteristics, gold is one of the few viable instruments to protect against monetary ruin and excessive debt. It is probably the only liquid asset independent of the relationship with the creditor. It is a means of payment independent of the government, accepted and recognized on all continents, which has survived every government failure and every war so far,” wrote Rahim Taghizadegan in the book “Austrian School Investment Practice. Between Inflation and Deflation.”

“Paper” gold rules the markets

It is worth recalling that the supply of gold is limited and stabilizes at around 3.5-4 thousand tons per year. As for the extraction of the royal metal, it is very difficult – the depth of gold mines reaches 4000 m – and expensive (costs are quickly approaching USD 2000 per ounce, or 31.1 g).

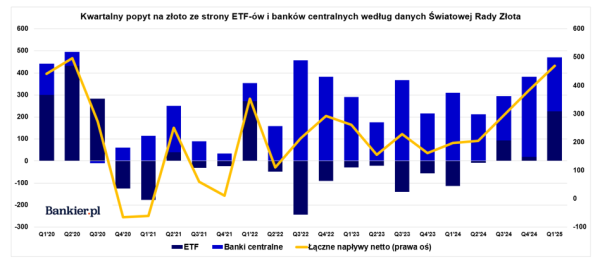

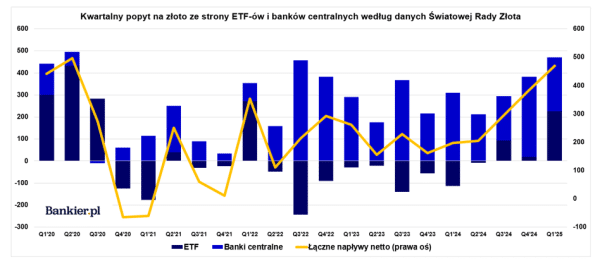

Importantly, the trade in physical gold does not even constitute 1% of the entire trade in this commodity. It is the derivatives market, not the physical metal, that influences the formation of the price of gold. As Michał Kubicki wrote, according to the latest data from the World Gold Council, ETF funds investing in gold recorded the largest purchases of the royal metal in over 3 years. The demand of the so-called street is accelerating, and according to investment banks’ forecasts, the support of gold ETFs may drive the price of gold to over USD 4,000.

Since the beginning of 2025 alone, gold prices in dollar terms have risen by almost 23%, although at times it has been as much as 31.7% after rising 27.2% last year and a 13.2% increase in 2023. Over the past five years, the price of the “barbaric relic” expressed in USD has doubled.

Bankier.pl

Geopolitics and the price of gold – a not coincidental connection

As mentioned, gold prices respond to the geopolitical situation, which has become increasingly complicated in recent years. Looking back, we can see how gold prices reacted to various wars. For example, in the run-up to the invasion of Iraq in 2003, the price of gold rose from around $320 per ounce in mid-2002 to around $370 in March 2003. After the outbreak of hostilities, the price of gold initially fell, which was the result of a short-term calming of the markets.

Also after the start of the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, investors rushed to gold, the price on the day of the invasion was about $1,900 per ounce and in a few days soared to the level of $2,076.60. Earlier, in 2014, after Russia’s annexation of Crimea, the price of gold rose from about $ 1,200 to $1,380.

Modern warfare, however, does not have to take place on a battlefield. During the first US-China trade war, initiated in 2018 by President Donald Trump, gold prices rose from around $ 1,200 in August 2018 to around $1,550 an ounce in September 2019.

Gold in times of recession – a crisis-proof asset

Gold often behaves inversely to stocks and other risk assets, especially during economic recessions. During the 2008–09 global financial crisis, the price of gold rose from around $800 per ounce in January 2008 to over $1,200 in December 2009. This increase was a result of increased demand for safe-haven assets and central bank actions such as quantitative easing.

It was no different during the Covid-19 pandemic, which caused a tsunami on stock markets. On March 16, 2020, the price of gold was “only” $1,451.50, and in August 2020, gold reached a record high of $2,077.50 per ounce. The increase at that time was caused, among other things, by fears of inflation resulting from government stimulus measures. These fears came true very quickly, in 2022-2023, in the face of rising inflation (exacerbated, among other things, by the energy crisis caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine) and economic uncertainty, the price of gold remained high, oscillating around $1,800-2,000.

Gold prices have been rising strongly since the beginning of this year, fueled by tariffs imposed and suspended by US President Donald Trump. April provided investors with a real rollercoaster. In the complicated economic and political puzzle, we also have a decline in confidence in the US, a vision of recession and Trump’s notorious attacks on the head of the Federal Reserve, Jerome Powell.

On April 22, the dollar gold price exceeded the level of $3,500 per ounce for the first time. This is not only a new nominal, but also a real record for the price of the royal metal expressed in USD. We had to wait over 45 years to break the record from January 1980. And that’s because the then $850/oz. in today’s money would be worth $3,493.95.

Gold and Central Banks

Over the last century, the gold market has undergone many changes that have had a significant and irreversible impact on the global economy and the currencies of most countries in the world. As recently as the 19th century, the royal metal was the basis of the gold standard, in which gold became a universally recognized international currency securing the value of paper money. After World War II, the Bretton Woods Agreement created a gold exchange rate system, and its value was used to determine the mutual exchange rates of the IMF member states.

Although the gold standard collapsed in 1971, when the United States stopped converting the dollar into gold, the royal metal remains an important element of central banks’ reserve assets to this day, serving not only as an element of asset diversification, but also as a hedge against currency and inflation risks.

In recent months, there has been significant purchase of gold by central banks. In the first quarter of 2025 alone, central banks purchased a total of 243.7 tons of gold. The largest institutional buyers included the National Bank of Poland (49 tons), which was also the largest buyer in all of 2024, the People’s Bank of China (13 tons), the National Bank of Kazakhstan (6 tons), the Czech National Bank (5 tons) and the Central Bank of Turkey (4 tons).

The National Bank of Poland continued to purchase gold in April, thanks to which Polish reserves of the royal metal exceeded the level of 500 tons and are already larger than those accumulated by the European Central Bank. April was also the sixth month in a row in which the official gold resources of the Middle Kingdom increased, although few believe in the official data, after many years of Beijing’s “golden silence “ .

In short, gold remains one of the most reliable assets in times of uncertainty. Its value as a “safe haven” has been repeatedly confirmed during periods of crisis, war and recession. The gold market’s reactions to geopolitics and the actions of central banks show that despite the development of technology and finance, the old rules have not yet become obsolete.

This is the first of the texts that we publish as part of the series Tydzień złotych. All of them can be found at this link.