Xander Schauffele produced a superb display to overtake Wyndham Clark for the outright lead after the third round of the Players Championship at Sawgrass.

US Open champion Clark – who was four ahead of Schauffele and Canada’s Nick Taylor overnight at 14-under par – started his round by digging out of the rough to make a birdie.

However, Olympic champion Schauffele continued to chase him down, sinking a 14-foot birdie on the sixth to close within two shots which was down to just one stroke at the turn.

After Clark found the water off the 12th tee before saving par, Schauffele capitalised with yet another birdie and then made a 58-foot putt at the 14th which saw him take a one-shot lead.

Clark, though, landed a 30-foot birdie on the par-five 16th to level things up again before finding the water at the 17th and opting to take another off the tee rather than a drop, which saw him make a four and so give Schauffele a one-shot lead heading to the 18th.

Schauffele tapped in his par for a superb 65, while Schauffele was two under for the day with his 70 for a 17-under total.

Open champion Brian Harman built on a solid start to sign for a 64, the best score of the week so far, as he put himself in contention at 15 under.

Harman found the trees at the par-five ninth, which resulted in him making a six, but he then picked up successive birdies with another from 17 feet on the 14th closing the gap on the lead.

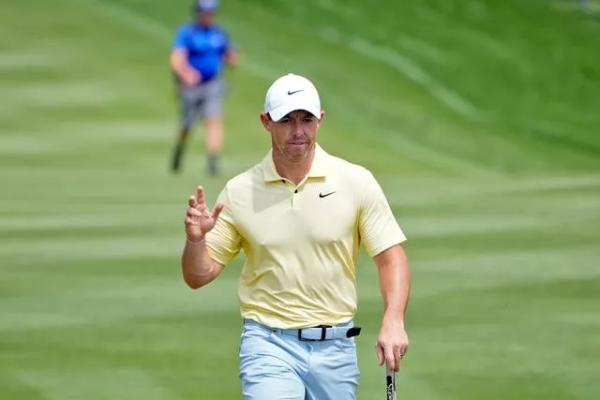

Rory McIlroy’s bid for a second Players Championship victory received a late rally with birdies on the final three holes to sign for a 69 and sit at nine-under overall.

The Northern Irishman, who had shared the first-round lead, went into the turn level, but made successive birdies from the 11th – only to then take a six on the 14th after finding the far greenside bunker.

However, three straight birdies from the 16th, when he played out from under the trees, gave the world number two some hope of making a late charge on Sunday.

World number one Scottie Scheffler continued to be troubled by a neck problem as he slipped down the leaderboard after a round of 68.

Scheffler – bidding to become the first player to successfully defend the Players Championship title in its 50-year history – came to Sawgrass on the back of an impressive five-shot win at the Arnold Palmer Invitational.

However, the American had needed treatment from a PGA Tour physio dudring his second round, and started Saturday with black tape on his neck.

A birdie at the par-five second was followed by a bogey at the fifth before Scheffler recovered another stroke on the next and headed into the turn at one under.

Scheffler found the water off the tee at the 12th, but recovered to save par and then made three birdies over the closing three holes to keep himself in the hunt at 12 under despite his fitness worries.

“I’m just battling, doing my best to just manoeuvre my way around the golf course, hitting shots,” he said after his round, describing the problem as “a little pain in the neck”.

“It’s very difficult to get the club back. Overall I’m just using my hands a lot, trying to hit shots. I would describe it as kind of slapping it around out there.

“I was proud of how I battled out there. To finish the round the way I did and still give myself a chance in this tournament is very good, and I’m definitely going to use that momentum going into tomorrow.”

Taylor, meanwhile, plummeted down the leaderboard after a bogey on the fourth was followed by a six at the par-four sixth, another at the ninth and then 10th. Although he picked up a couple of shots from the next, yet another bogey on the 18th saw him finish with a four-over 76.

England’s Matt Fitzpatrick recovered from a double bogey on the fourth and another dropped shot two holes later to finish with four birdies on the back nine in his 68.

Fitzpatrick is tied for fourth at 13 under alongside Maverick McNealy, who hit a second successive 68, while an eagle on 16 helped Sahith Theegala to a 67, which sees him one stroke back in a tie for sixth alongside Scheffler.

Sourse: breakingnews.ie